BY ELIAS GROLL

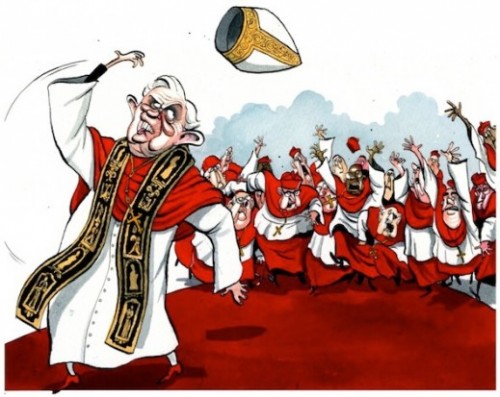

If a report on Thursday, Feb. 21, in the Italian newspaper La Repubblica is to be believed, Pope Benedict XVI’s recent decision to resign just got a whole lot more interesting. The paper claims that around the time that Pope Benedict decided to step down, the pontiff learned of a faction of gay prelates in the Vatican who may have been exposed to blackmail by a group of male prostitutes in Rome. The revelations allegedly appeared in a 300-page report by three cardinals that the pope commissioned to investigate the release of internal documents by his butler, the so-called “Vatileaks” scandal. (A Vatican spokesman has refused to confirm or deny La Repubblica’s claims, and the internal Vatican report is reportedly stowed away in a papal safe for Pope Benedict’s successor to peruse.)

Seen in the context of Pope Benedict’s career in the Catholic Church, it is difficult to understand why revelations of yet another sex scandal would push him to resign. For over a decade, he has served as the church’s point person for responding to allegations of abuse. From 1985 until his election to the papacy in 2005, Benedict served as the head of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, a powerful Vatican body charged with policing church doctrine. In 2001, Pope John Paul II transferred responsibility for dealing with the sex scandals enveloping the institution to then-Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger’s office. In that role, Ratzinger received tens of thousands of complaints alleging sexual abuse of children by Catholic priests. Those documents often went into lurid detail, and Ratzinger is said to have been deeply affected by the experience.

Seen in the context of Pope Benedict’s career in the Catholic Church, it is difficult to understand why revelations of yet another sex scandal would push him to resign. For over a decade, he has served as the church’s point person for responding to allegations of abuse. From 1985 until his election to the papacy in 2005, Benedict served as the head of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, a powerful Vatican body charged with policing church doctrine. In 2001, Pope John Paul II transferred responsibility for dealing with the sex scandals enveloping the institution to then-Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger’s office. In that role, Ratzinger received tens of thousands of complaints alleging sexual abuse of children by Catholic priests. Those documents often went into lurid detail, and Ratzinger is said to have been deeply affected by the experience.

As a theologian and head of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, Benedict gained the not-so-flattering nickname “God’s Rottweiler” for his rigid interpretations of doctrine and his stringent enforcement of church rules. In practice, he has frequently displayed a preference — both as a pope and as a cardinal — for confronting predatory priests behind closed doors and protecting the church’s reputation at the expense of public accountability.

Here’s how Benedict tackled some of the most prominent scandals to have struck the church during his career.

Peter Hullermann, Germany, 1980

While serving as the archbishop of Munich, Ratzinger may have played a role in shielding a pedophile priest, Peter Hullermann, from prosecution, transferring him to different parishes when parents complained that he had abused their children. In 1980, Ratzinger approved a plan to send Hullermann, who was facing allegations (that he did not deny) of abusing children in the German city of Essen, to Munich for therapy. Over the objections of a psychiatrist who was treating the priest, the German archdiocese permitted Hullermann to resume his pastoral work shortly after beginning therapy and did not inform the priest’s new parish of his history. In 1986, Hullermann was convicted of sexual abuse in Bavaria.

Lawrence Murphy, United States, 1996

As head of a Wisconsin school for deaf boys from 1950 to 1974, Father Lawrence Murphy is alleged to have molested upwards of 200 children. Yet when the case was presented to Ratzinger in the mid-1990s, he declined to defrock the priest. In 1996, Ratzinger ignored letters from Rembert Weakland, the archbishop of Milwaukee, seeking guidance from the cardinal on how to proceed against Murphy and another priest. Eventually, the church initiated a canonical trial against Murphy, but when the priest personally appealed to Ratzinger for clemency, saying that he was in poor health, the cardinal intervened to stop the proceedings against him.

2001 Letter to Bishops

After being tasked in 2001 by Pope John Paul II to assume responsibility for sex abuse allegations, and after gaining access to a trove of documents that laid out allegations against abusive priests, Ratzinger took action. He did so in a 2001 letter sent to every one of the church’s bishops. In it, Ratzinger laid out the church’s guidelines for investigating claims of sexual abuse, which asserted that the church — and not civil authorities — still held primary authority over investigations and that the church had a right to keep evidence in such cases confidential until 10 years after a minor turned 18. That assertion led to charges by victims’ rights advocates that Ratzinger had committed worldwide gross obstruction of justice, a charge that critics saw as compounded by Ratzinger’s assertion in the letter that such cases required absolute secrecy. Breaking the code of silence carried a range of penalties, among them excommunication. Ratzinger’s order effectively removed the possibility that sex abusers would be brought to justice in lay courts and guaranteed that the church would retain its investigatory prerogative.

Eamonn Walsh and Raymond Field, Ireland, 2010

In an attempt to help bring closure to victims affected by sexual abuse in the Irish Catholic Church, two auxiliary bishops, Eamonn Walsh and Raymond Field, accused of helping to cover up rampant abuse offered Pope Benedict their resignation in 2010. In a move that stunned critics of the church and victims’ rights groups, the pope rejected their resignation and informed the bishops that they would be allowed to stay on in the church, despite the fact that other priests accused of covering up the scandal were allowed to resign. “By rejecting the resignations of two complicit Irish bishops, the Pope is rubbing more salt into the already deep and still fresh wounds of thousands of child sex abuse victims and millions of betrayed Catholics,” said Barbara Blaine, president and founder of the Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests, in a statement. “He’s sending an alarming message to church employees across the globe: even widespread documentation of the concealing of child sex crimes and the coddling of criminals won’t cost you your job in the church.”

2010 Apology to Ireland

By 2010, the hard-line strategy advocated by Pope Benedict became unsustainable. Explosive and wide-ranging reports of abuse — including allegations against Ratzinger himself during his time in Munich — put the church firmly in the cross-hairs of public opinion. Detailed investigations by the Irish government unearthed widespread abuse, and Ireland became something of a ground zero for the scandal. In response, Pope Benedict issued a public apology to his parishioners in Ireland. “You have suffered grievously and I am truly sorry. I know that nothing can undo the wrong you have endured,” the pope wrote. “Your trust has been betrayed and your dignity has been violated. Many of you found that, when you were courageous enough to speak of what happened to you, no one would listen.” Priests read the letter aloud in church.

But if the apology to Ireland signaled a willingness within the church to more openly confront its past, subsequent guidelines to bishops quashed that notion. In 2011, Pope Benedict issued new guidelines that reaffirmed bishops’ authority in adjudicating cases. Although that letter underscored the importance of stopping the abuse of minors, victims remained dismayed at the lack of an enforcement mechanism.

Complete Article HERE!