How a Catholic bishop secretly sent money from a church hospital to a cardinal in Rome

The idea came to West Virginia Bishop Michael J. Bransfield while he was in Rome visiting an old friend, a powerful cardinal at the Vatican. Bransfield thought the cleric’s apartment was barren and lacked a comfortable room for watching television.

After Bransfield returned to West Virginia, in May 2017, he sent the cardinal a $14,000 check. “I fixed that room up for him,” Bransfield said in an interview with The Washington Post.

The gift, one of two Bransfield sent to Cardinal Kevin Farrell, was an extraordinary gesture from a religious leader in a state plagued by poverty. Even more unusual was how Bransfield obtained the cash he gave away.

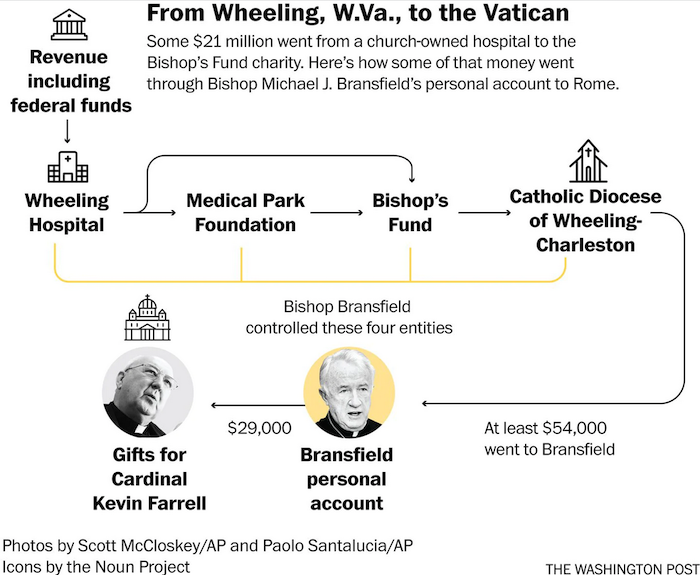

The untold story behind those gifts illustrates how $21 million was moved from a church-owned hospital in Wheeling, W.Va., to be used at Bransfield’s discretion. It adds a new dimension to a financial scandal that has rippled through the Catholic Church since Bransfield’s ouster last year.

A Post investigation found that the money Bransfield sent to Farrell was routed from Wheeling Hospital to the Bishop’s Fund, a charity created by Bransfield with the stated purpose of helping the residents of West Virginia, tax filings show.

As Bransfield prepared to write the first of his personal checks to Farrell, a church official arranged to transfer money from the Bishop’s Fund into a diocese bank account — and then from there to Bransfield’s personal bank account, an internal email obtained by The Post shows.

“Bishop Bransfield made very specific requests,” said Bryan Minor, a Bishop’s Fund board member and diocese employee who wrote the email and arranged the transfers for the gifts to Farrell. “He wanted to have a discretionary fund.”

Bransfield used Bishop’s Fund money for a variety of purposes, including church projects in West Virginia that burnished his reputation as a generous benefactor.

The bishop also drew on it to send the second check to Farrell for the apartment, this time for $15,000, church financial records and emails show.

In all, $321,000 was sent out of West Virginia, in apparent contradiction to the stated purpose of the Bishop’s Fund, The Post found. Church officials have declined to identify the out-of-state recipients.

The hospital was the charity’s only source of funding, tax filings and hospital audits show. As a nonprofit institution that relies heavily on federal funding through Medicare, the hospital is subject to restrictions on how it uses its money.

In the interview with The Post over the summer, Bransfield defended the cash gifts to Farrell, saying they were “funds that I had raised.” He and his attorney did not respond to subsequent questions about The Post’s findings.

Bransfield stepped down in September 2018 amid allegations he misused church money and sexually harassed seminarians and young priests, claims that he has denied. He has since been stripped of his clerical authority and ordered to leave the West Virginia diocese.

During his 13-year tenure at the Diocese of Wheeling-Charleston, Bransfield spent millions of dollars of diocese money on extravagances, including travel on chartered jets, lavish furnishings at his official residence and nearly 600 cash gifts to fellow clergymen, according to the findings of an internal church investigation previously obtained by The Post.

Church officials have declined to release the investigators’ confidential report, but a Post story in June detailed many of its findings.

To support his lavish spending, Bransfield long relied on oil revenue from land in Texas that was left to the diocese more than a century ago. The church investigators wrote that he created the Bishop’s Fund in 2014 to serve as a “vehicle” to also access and spend hospital money, a finding that has not previously been reported.

The Post determined that the money sent to Farrell and others outside the state originated at the hospital by examining tax filings and internal church documents and emails as well as other records.

Minor, the diocese’s human resources director, told The Post in an interview that he understood the transfers to be legally permissible and properly authorized.

Spokesmen for the diocese and hospital declined requests for comment about the Bishop’s Fund.

Two members of the hospital board, Sister Mary Palmer and Richard Polinsky, said in interviews that they had never heard of the Bishop’s Fund and did not recall approving multimillion-dollar transfers.

A third board member, retired FBI agent Thomas Burgoyne, questioned how any money that started in the hospital ended up passing through Bransfield’s personal account. “Based on my experience in law enforcement, this is something that needs to be looked at,” said Burgoyne.

Two tax law specialists and a former federal prosecutor who examined related documents at The Post’s request agreed, citing laws that restrict how federally funded hospitals and nonprofit groups can use money.

Under one federal law, hospitals that receive substantial federal benefits through programs such as Medicare are prohibited from directing money to any entity or person without proper authority or purpose. Under another, charity money may not be used to unduly benefit an individual.

“Lining the pockets of private citizens, even when those private citizens are priests, is a violation of charities and tax law,” said Jill Horwitz, professor and vice dean of the University of California at Los Angeles law school.

In recent weeks, the Justice Department has sought information about the transfers to the Bishop’s Fund as part of a lawsuit that accuses the hospital of defrauding the federal government of millions of dollars by filing false claims for Medicare reimbursement. Hospital officials deny the allegations.

A diocesan windfall

From the time he became bishop in 2005, Bransfield poured church money into building projects and other work, while also spending on personal luxuries for himself, according to the confidential investigative report.

But he faced mounting criticism from parishioners for his extravagances after local news accounts of his spending on his church residence, a chauffeur and a personal chef. Bransfield has defended his spending as appropriate.

By 2014, the bishop was seeking a way to continue spending on projects of his choosing without “making the subsequent donations appear to be coming from the DWC,” according to the confidential investigative report, using the shorthand for the diocese.

He found an answer in the coffers of Wheeling Hospital.

Bransfield, as bishop, served as chairman of the hospital board. Long a money-loser, the hospital experienced a financial turnaround under consultants hired to lead it after Bransfield’s arrival in Wheeling. Revenue soared and cash on hand skyrocketed, financial statements show. Much of its revenue came from Medicare and Medicaid reimbursement.

The hospital’s operations included a self-insurance entity, Mountaineer Freedom Risk Retention Group, which pooled hospital money to offset malpractice claims. Bransfield found “extra pockets of cash” on Mountaineer’s balance sheet, according to the confidential investigative report.

He “felt he should be able to have access to that money,” the report said.

In December 2014, Bransfield created the Bishop’s Fund. The stated purpose of the charity was “to provide for the pastoral care of the diocese” and “charitable care of the people of the diocese,” tax filings show.

Church investigators later concluded that the fund was a “vehicle for Bransfield to access [Mountaineer] money and spend on projects of his choosing,” according to their report.

The financial transfers from the hospital began in 2015. They involved multiple steps and were carried out with help from hospital administrators, Bransfield aides and allies on the boards of multiple nonprofit groups.

The first step involved the closure of Mountaineer Freedom Risk and the creation of a new self-insurance entity. During the changeover, hospital officials carved out $8 million from Mountaineer and gave it to another hospital subsidiary, a charitable group called the Medical Park Foundation, hospital audits show.

In state incorporation filings, Medical Park said it existed to raise contributions for the benefit of Wheeling Hospital and the “sick, injured, disabled, infirm, aged and poor” in the community.

Medical Park, run by several hospital executives and board members, transferred the $8 million to the Bishop’s Fund, according to state records and tax filings.

In 2016 and 2017, the hospital gave another $13 million to the Bishop’s Fund, some directly and some through Medical Park, tax filings show.

Hospital officials referred questions about those transfers, including whether the board had approved them, to an outside lawyer, David Paragas.

Paragas initially agreed to answer questions but later sent an email saying the hospital would not do so. “At this stage, it would be inappropriate for Wheeling Hospital to comment,” Paragas wrote.

n the interview with The Post, Minor said he had no knowledge of how the transfers from the hospital came about. The next day, he wrote in an email that he had checked with a hospital attorney and was told that the hospital board had approved the transfers.

“The board acted on the advice of independent counsel for the hospital, the transactions were reviewed by independent counsel for the hospital, and the transfers were approved by the board,” he wrote.

He declined to provide minutes documenting those votes and said he had no further comment.

Palmer and Polinsky, who served together on the hospital board for a decade, said they would have recalled votes for such large transfers.

“It would be unusual and eye-catching at a meeting to say, ‘We’re going to take this amount of money and send it to an open fund that the bishop would have,’ ” said Polinsky, who served on the board until late last year. “I have no recollection of anything like a Bishop’s Fund.”

Palmer said she was never told about the Bishop’s Fund. “I’m not aware of any approval, or even that it was brought up,” she said.

The lay investigators who prepared the confidential report about Bransfield wrote that they also found no indication the hospital board approved the transfers. Their work included an interview with the hospital president, Msgr. Kevin Quirk, who was also on the board of the Bishop’s Fund and served as a top aide to Bransfield in the diocese. He did not respond to messages seeking comment for this story.

“We found no evidence that the Board of the Hospital was consulted or approved the establishment and funding of The Bishop’s Fund,” the investigative report said.

Msgr. Frederick Annie, who served on the hospital board, “rolled his eyes” when investigators asked about the board’s oversight role, “suggesting an absence of any meaningful review,” the confidential investigative report said.

Funding a legacy

Though few parishioners knew about the Bishop’s Fund, most of the group’s money made its way to projects and initiatives across the state. Among the beneficiaries were select Catholic schools and churches in West Virginia, tax and church records show. In local news accounts, the recipients were often quoted praising Bransfield personally for his generosity.

The largest amount by far went to a financially troubled Catholic university in Wheeling that had no formal affiliation with the diocese. Wheeling Jesuit University had asked Bransfield for financial assistance because it was buckling under massive debt and declining revenue.

Bransfield, nearing retirement, saw a chance to expand the diocese’s real estate holdings and add luster to his reputation, according to Mark Phillips, then the chief of staff at Wheeling Jesuit, who regularly met with Bransfield to discuss the school’s fate.

“Bransfield was very concerned about his legacy,” Phillips wrote to The Post. “He clearly saw the investments in the Diocese, Wheeling Hospital, and the University as his personal gifts to West Virginia.”

In 2016 and 2017, the Bishop’s Fund gave a total of $12.6 million to the university to help keep it afloat. In exchange, the diocese gained control of the university and its campus near the Ohio River. The school, now known as Wheeling University, continues to struggle financially.

Bishop’s Fund grants helped pay for a new air conditioning system at the gymnasium of Wheeling Central Catholic High School. School President Lawrence Bandi, who at the time served on the board of the Bishop’s Fund, renamed the facility after Bransfield.

“This was a great opportunity to acknowledge the generosity of the bishop,” Bandi said at the unveiling. Bandi did not respond to phone calls seeking comment. The high school stripped Bransfield’s name from the gym earlier this year.

The Bishop’s Fund also spent $400,000 on a custom-made Italian altar set that was rejected last fall by parishioners at a church in Wheeling who objected to Bransfield’s lavish spending. The altar now sits in a storage facility, a diocese spokesman said.

Bransfield also wanted to use the Bishop’s Fund to send donations and cash gifts outside of West Virginia, according to the investigative report. But there was a problem. The charity had reported to the Internal Revenue Service that its efforts were exclusively devoted to helping people in West Virginia.

Bransfield and his aides decided they could avoid that impediment by using the diocese as a “pass-through,” Minor said.

“I thought that was legal and, according to accounting, that we could make a grant to the diocese and that the diocese could make a grant as a pass-through to a Catholic entity,” Minor said during the interview at his home.

Minor provided The Post with a Bishop’s Fund document listing grants made by the group totaling $17 million. The money given to the diocese and sent out of West Virginia — including money for Farrell’s apartment — was described only as supporting “operations.”

The Post determined that some $60,000 of that was donated through the diocese to the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in the District, where Bransfield had worked as a finance director and rector. The donation was used to help renovate the church’s iconic dome, according to a spokesman for the National Shrine.

Disbursements related to the two gifts for Farrell’s apartment in Rome account for another $54,000.

Farrell was one of more than 130 clergymen, including more than a dozen cardinals, who received cash gifts totaling $350,000 from Bransfield during his time in West Virginia, The Post previously reported. Most of those gifts predate the creation of the Bishop’s Fund.

Bransfield wrote the checks from his personal account. The West Virginia diocese reimbursed him by boosting his compensation to cover both the value of the gifts and the taxes he would owe on the added compensation, church investigators found.

As a tax-exempt organization, the diocese is supposed to use its money only for charitable purposes and may not excessively enrich any individual, according to IRS rules.

In addition to the $29,000 that went to Farrell, the diocese paid Bransfield $25,000 to cover the income taxes Bransfield would owe, drawing all of the money from the Bishop’s Fund, according to church documents and interviews with Minor and Bransfield.

Multiple emails among diocese leaders directly link the money from the Bishop’s Fund to the Farrell gifts.

“Hey there. Just a note that I need to order a check from The Bishop’s Fund, payable to DWC, to cover a check as a gift to Abp Kevin Farrell at the Vatican,” Minor wrote on May 12, 2017.

In statements to The Post earlier this year, Farrell and more than a dozen other recipients of Bransfield’s gifts said they had presumed the money was the bishop’s. Farrell and the others pledged to repay the diocese.

A Vatican spokesman confirmed this month that Farrell had done so.

Farrell is a close adviser to the pope and an influential figure in the church. He and Bransfield became friends in the 1980s and 1990s, when both held church posts in Washington.

The men had the same mentor, former cardinal Theodore McCarrick, a legendary fundraiser for the church who was defrocked after the church found him guilty of sexual abuse. Bransfield and Farrell also served together on the influential Papal Foundation, a charity that raises money from wealthy American Catholics for initiatives chosen by the pope.

The gifts to Farrell and other clerics were cited in a letter by Quirk, Bransfield’s aide, as an example of his alleged misconduct.

Quirk’s August 2018 letter to Baltimore Archbishop William Lori, obtained by The Post, accused Bransfield of trying to buy influence in the church. Quirk wrote that Bransfield was seeking help from Farrell to arrange a one-on-one visit with the pope last fall.

“It is my own opinion that His Excellency makes use of monetary gifts, such as those noted above, to higher ranking ecclesiastics and gifts to subordinates to purchase influence from the former and compliance or loyalty from the latter,” Quirk wrote.

Bransfield denied Quirk’s allegation. “I didn’t do these things for people to give me something,” he told The Post in July.

Lori, as acting administrator of the diocese, announced in July that he was shutting down the Bishop’s Fund as part of a package of reforms to improve financial oversight in the wake of The Post’s revelations about Bransfield’s conduct. Lori did not detail the concerns about the charity or describe its financial link to the hospital.

“When a bishop is entrusted to care for a diocese, he is expected to be a wise and honest steward of its resources,” Lori wrote in an open letter to Catholics. “But here in Wheeling-Charleston, these procedures and policies did not prevent the bishop from misusing diocesan funds.”

A spokesman said the $4 million remaining in the charity coffers would be transferred to the diocese.

‘It is my hospital’

The Justice Department lawsuit against Wheeling Hospital, based on a whistleblower’s claim, was unsealed in March and is still in its early stages. It alleged that the hospital and its then-leader, Ronald Violi — named as a defendant and described in court records as Bransfield’s “hand-picked” chief executive — were responsible for thousands of false claims for reimbursement from the federal health-care program for the elderly.

Justice said that the hospital’s financial turnaround was driven in part by the alleged scheme.

The lawsuit said the executives “reported to and took direction from Bishop Bransfield,” who personally maintained control over hospital operations and set the pay of the chief executive.

“It is my hospital,” Bransfield often said, Violi told Justice Department lawyers in a recent deposition.

Bransfield was not named as a defendant.

The hospital has described the allegations as “an unfair attack” on its values and physicians.

Violi stepped down as chief executive earlier this year. He has denied wrongdoing. His attorney did not respond to requests seeking comment for this story.

In a filing this month, Justice Department lawyers sought information about Violi’s relationship with Bransfield and about the transfers to the Bishop’s Fund.

They alleged that Bransfield increased Violi’s compensation at the same time the hospital was directing “a large amount of its (allegedly ill-gotten) profits towards the Diocese and the now-dissolved Bishop’s Fund.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!