This video is part of Women’s Ordination 101 – a resource for a renewed Church

The Gay Catholic Priests' Blog

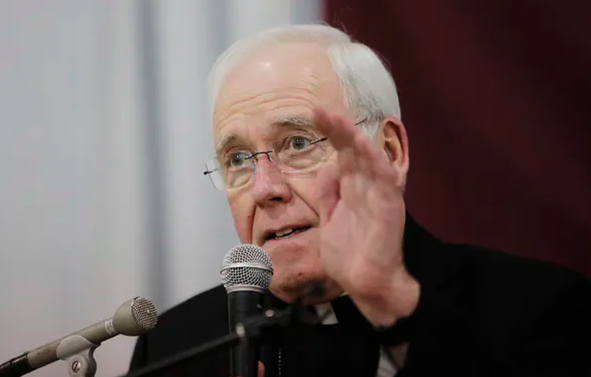

Roman Catholic Bishop Richard Malone resigned in December 2019 after intense public criticism for his handling of the clergy sexual abuse crisis in the Diocese of Buffalo, New York.

His departure came three months after the Vatican announced what’s called an “apostolic visitation” – a religious investigation that allows the pope to swiftly audit, punish or sanction virtually any wing of the Roman Catholic Church – into Malone’s diocese, or region.

In my research on clergy sexual abuse, I’ve learned that these investigations are still shrouded in secrecy.

When clergy abuse cases first emerged in the 1980s, the Vatican used apostolic visitations to punish Catholic institutions who had attracted negative press for their role in the scandal.

After lawmakers in Ireland, Canada and the U.S. suggested that seminary training was a potential cause of the clergy sex abuse crisis, for example, the Vatican ordered visitations to investigate the entire network of seminaries in those countries.

Though the full results of these investigations are rarely made public, resignations of troublesome clergy typically follow.

Bishop Robert Finn of Kansas City, for example, refused to leave office even after he was convicted in 2012, by the circuit court of Jackson County, Missouri, for his failure to report child sexual abuse. After awaiting his resignation for two years, the Vatican pressured Finn by opening a visitation in 2014. He promptly resigned after the Vatican’s investigation.

In the ancient church, popes used apostolic visitations to govern far-flung regions. But since the creation of separate political delegates in the 16th century, visitations have been used more for emergency situations.

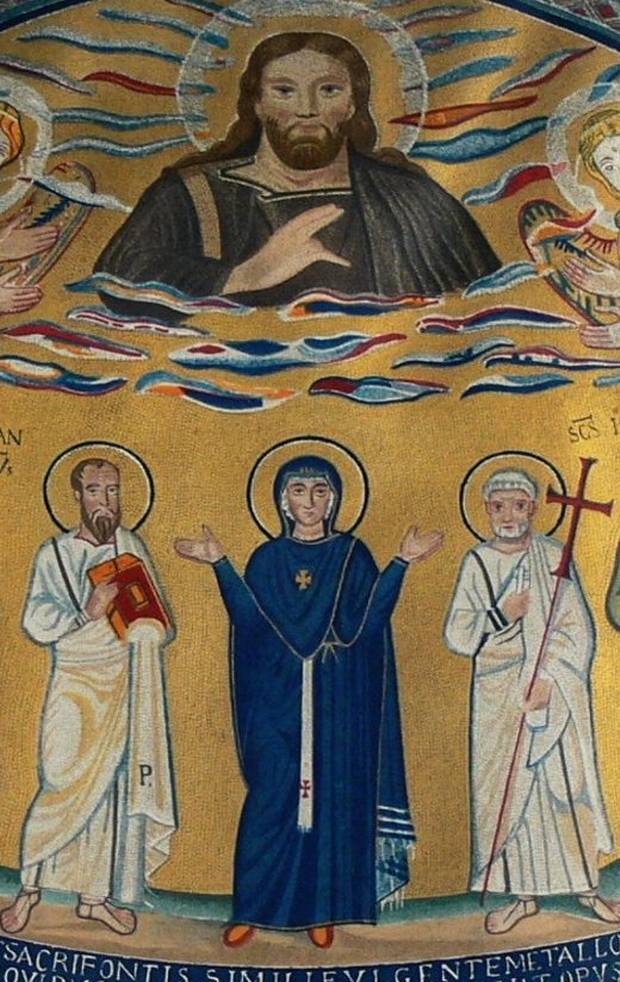

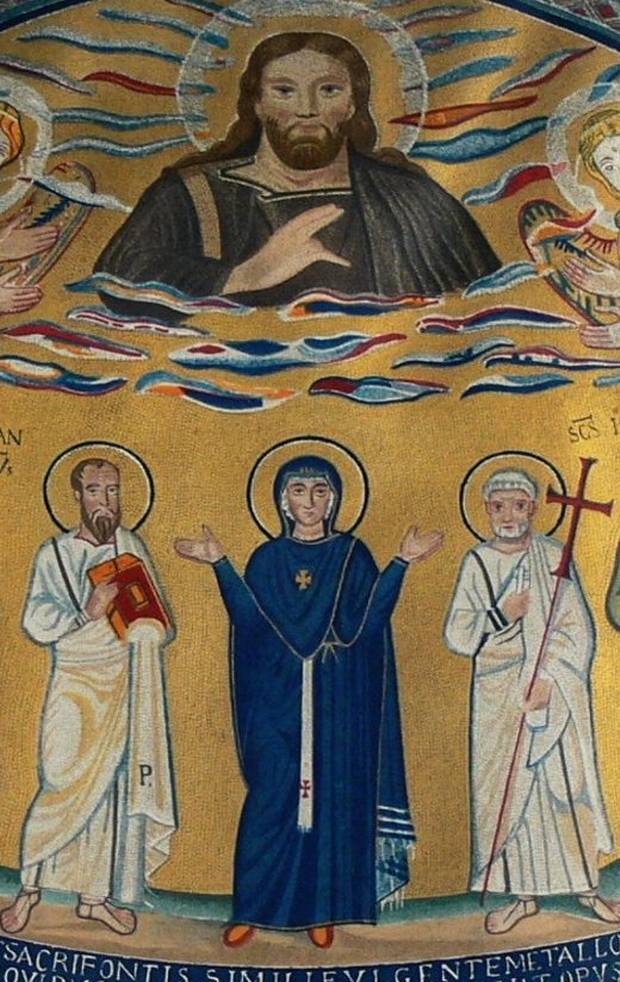

The theology underpinning apostolic visitations comes from the Christian Bible, particularly passages from the Gospel of Mark and St. Paul’s Letters, which urged early Christians to supervise one another.

The medieval Catholic empire was so diffuse that bishops had to travel long distances to “visit” their communities. Those yearly visits are still called “canonical visitations” because they are described in canon law, the regulations that govern clergy.

Unlike mundane canonical audits, apostolic visitations are special investigations ordered by the pope, who chooses a delegate, or “visitor,” to lead the inquiry. The Vatican has sole discretion over the purpose, scale and duration of the investigation.

They are called “apostolic” because the church teaches that the bishops are heirs to Jesus’ apostles, and so only the pope can fire a Catholic bishop.

Some apostolic visitations are launched over doctrinal, rather than criminal, emergencies. In 2007, for example, Pope Benedict used a visitation to punish a liberal Australian bishop.

The bishop, William Morris, infuriated Benedict by openly advocating for women’s ordination, which contradicts the Vatican policy that only men can be priests. That secret visitation sparked a years-long standoff in which Morris repeatedly refused the Vatican’s order to resign, forcing the pope to publicly fire him.

In theory, apostolic visitations need not be punitive. They could instead serve as a constructive way for the pope to delegate bishops to work as internal consultants or executive coaches for struggling units within the church, which oversees an estimated 1.3 billion Catholics worldwide.

However, Catholic laws define visitations in explicitly judicial terms, and scholars have concluded that the investigations are nearly always a form of discipline.

Visitations are highly secretive. Even when the Vatican acknowledges that an visitation is underway, it seldom discloses the pope’s reasoning for opening the inquiry, let alone the full findings of the investigation.

This lack of transparency has been condemned by some Catholics who expect the modern church to hold fair and open trials.

The Vatican was widely criticized, for example, for its inability to articulate why it investigated all 60,000 nuns in the United States. Pope Benedict initiated that controversial visitation in 2008, only to have it quietly closed in 2014 by his successor, Pope Francis, who did not impose any changes on American nuns.

In the case of Bufallo’s Bishop Malone, none of the visitation’s findings have been shared publicly. In his official statement, Malone defended his handling of clergy abuses before explaining that “prayer and discernment” had led him to resign.

Malone admitted that the apostolic visitation was “a factor” in his decision, but he was also adamant that the pope had not forced him to retire.

The authoritarian and top-secret nature of apostolic visitations makes it impossible to know whether the Vatican discovered any new allegations of child sexual abuse in Buffalo. The integrity of the visitation has also been called into question, because the inquiry was led by a bishop who is himself now under investigation for allegations of child sexual abuse.

As a result of all this secrecy, the public cannot know whether Pope Francis is being proactive in his outreach to survivors, especially to victims from dioceses where the bishop is suspected of having concealed the church’s crimes.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

By Emily Alford

Over the last year and a half, 178 U.S. dioceses serving 64.7 million Catholics have released lists of priests “credibly accused” of sexual abuse. However, the problem with these lists is that they exist independently of one another, with no consensus as to what makes an accusation credible. This lack of organization makes it difficult for members of one parish to get a full picture of past accusations, leaving surviving victims feeling as if their abusers are still hiding in plain sight, with potential victims ignorant of past allegations. In order to address this problem, ProPublica combed through all existing abuser lists released by dioceses and organized them into one searchable master list.

In 2018, a Pennsylvania grand jury report listed hundreds of priests accused of abuse across the state as part of a sweeping investigation, which prompted dioceses across the country to release similar lists. One of the major problems with these lists, according to ProPublica, is that there is no standard for what constitutes a credible allegation, leaving many abusers unnamed. For example, in February 2019 Larry Giacalone was paid a $73,000 settlement by the church after coming forward to name his alleged abuser, a priest by the name of Richard Donahue. However, when the Boston Archdiocese released its list of names soon after, Donahue’s name was missing. After facing pressure from Giacalone’s attorney’s the priest’s name was added to the “unsubstantiated” portion of the list.

Decisions about how and whether to form and release these lists are left to individual dioceses. And while the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops can offer suggestions and guidelines, a spokesperson for the organization, Chiedo Noguchi, explained that ultimately bishops answer to the pope, not the USCCB:

“Recognizing the authority of the local bishop, and the fact that state and local laws vary, the decision of whether and how to best release lists and comply with varying civil reporting laws have been the responsibility of individual dioceses.”

This lack of guidelines makes it much more possible for abusers to hide, even after public allegations, and churches are able to divide cases into “credible” and “incredible” with no input from courts or law enforcement, according to the ProPublica report:

“The Archdiocese of Seattle, which released its list prior to the grand jury report, began by dividing allegations into three categories: cases in which priests admitted the allegations or where allegations were “established” by reports from multiple victims; cases that clearly could not have happened; and cases that fell into a gray area, like those that were never fully investigated at the time they were reported. The archdiocese decided it would name priests whose cases fell into the first category and leave out the second group, but it sought additional guidance on the third set of cases.”

In many cases, dioceses also leave off the names of priests who have died since being accused, and 41 dioceses serving nine million U.S. Catholics have yet to release any lists whatsoever.

In order to better organize and distribute information about sexually abusive priests, ProPublica has organized all 178 of the existing lists into a searchable database, allowing users to search by priest name, parish, or diocese. The more accessible list enables searchers to track priests who appear on multiple lists, a feat that proved incredibly difficult when information was scattered.

However other groups, like Bishop Accountability, say there is much more work to be done. The group forms its own list of accused priests based on court and church documents as well as news reports and includes 450 names from dioceses that have failed to create their own lists. Furthermore, accusations against orders like Jesuits, members of their own order who often work in parishes and schools, are often not included in any lists, as they are technically outside the diocese. According to Jerry Topczewski, chief of staff for Milwaukee Archbishop Jerome Listecki, the task of counting up every single abuser who has or may be committing sexually abusing prisoners is simply too difficult:

“At some point you have to make a decision,” Topczewski said. “Someone’s always going to say your list isn’t good enough, which we have people say, ‘Your list is incomplete.’ Well, I only control the list l can control and that’s diocesan priests.”

But David Clohessy, who led the Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests for 30 years, says that putting together better, more accessible lists isn’t nearly as difficult as Catholic authority figures are making it seem:

“They continue to be as secretive as possible, parceling out the least amount of information possible and only under great duress,” Clohessy said. “They are absolute masters at hairsplitting — always have been and still are.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Every Sunday at 10:30 a.m., Father Charles celebrates mass in Bziza, a rural village in north Lebanon. On this particular day in January, he tells the congregation of a hundred how angel Gabriel revealed to Mary that she was pregnant. Then they stand to sing and kneel to pray.

After the Eucharist, Charles Kassas takes off his white cassock to join his wife Brigitte and their three children — Nadim, Celine and Mathieu. In Western countries where priests must take vows of chastity that scene would cause a scandal, but in Lebanon it is very common.

“Of course I know he is married, so what? It would be strange if he weren’t!” says an old woman exiting the church.

In Bziza, the majority of the population is Christian Maronite — members of the Eastern Catholic Church founded in the 5th century. It follows the Vatican but does not require priests to be single. As a result, more than half of the priests in Lebanon have a family.

In Lebanon, other catholic communities — including Greek Catholics, Armenian Catholics and Syrian Catholics — also widely accept married priests.

For Kassas, there is no contradiction between conjugality and the call of God — in fact, it is just the opposite. He thinks that having a family gives him personal balance. “You can’t serve others if you are not at peace. Being a husband to my wife and a parent to my children helps me being a better father to the parish,” he told Al-Monitor.

Charles and Brigitte have been married for over 20 years. In small parishes like this one, the priest’s wife has an important social role. In Arabic, she is called “khouriye,” the feminine for “khoury” — priest.

“She is the strength that holds up our family and she is a real partner for me,” Kassas added.

A priest’s wife is expected to attend church celebrations and all other events such as births, christenings, weddings and funerals. She can sometimes give advice and is the go-to person when her husband is unavailable. Their family home must be open to visitors 24/7.

“It’s not easy at all. When I got married I didn’t know being a priest’s wife would require so much. There is always something to do, someone to visit, someone to accommodate,” she told Al-Monitor.

To prepare women to endorse that role, several priests’ wives have set up workshops and training programs for young brides.

In larger towns and cities, priests tend to work from an office. Their homes are private and their wives have fewer responsibilities toward the churchgoers.

Married priests are a tradition that dates back to the early days of Christianity, before the Latin Church banned it in the 11th century. For a long time in Lebanon, villagers would choose their priests from among married men who had already proven they could be in charge of a family. Those who wished to remain single would join monasteries to become monks.

Today, the question of whether or not to get married usually arises during seminary studies in Lebanon.

Charles took his decision when he was 25, during his fourth year of theological studies. “I came to the conclusion that I wanted to join priesthood, but I also deeply wished to have a family. I felt the need to be loved by a woman and to have children,” he told Al-Monitor.

When asked if he would have been able to give up family life for God, like European priests do — he said he wouldn’t have. “Some people can live like hermits — I can’t. I don’t have the capacity to endure that kind of loneliness,” he said.

Allowing married men to become priests is also a way for the Church to welcome older people who have had another life before.

This is the case of Mansour Zeidan. At the age of 36, he is about to switch careers. For the time being, he is the proud owner of Mr & Mrs Clown, a birthday events company he created 10 years ago. But costumes and party decorations will soon be part of his past. In a few weeks, he will be ordained priest.

“I’m afraid he will spend all his time in church and leave me alone with our son,” Yolla, his wife, said.

“I wanted to have the time to try several things before making my decision,” he said, listing his previous jobs as a supermarket cashier, night watchman, site manager and school supervisor.

Zeidan is studying hard to join priesthood. He takes theology courses at the university and is finishing a practical training in a church near Beirut.

Father Marwan Mouawad, who is also married, teaches him how to draw on his experience as a family man to feed his relationship with the faithful. “When it comes to man and wife issues for instance or the parent-child relationship, it is not just theories for us; we can take examples from our personal lives and for people that is very important,” Mouawad told Al-Monitor.

At night, Zeidan joins a group of seminarians in Burj Hammoud, a deprived neighborhood near Beirut. Between meal distributions and prayer circles, future clerics discuss marriage.

“Being a priest is a vocation but so is having a family. It is dangerous to stifle an inner desire at the expense of the other; you can never be happy that way,” said Charbel Fakhry, a 29-year-old seminarian who chose celibacy.

While married men can become priests, it does not work the other way around. Priests who are ordained while single can’t change their minds later. They can aspire, however, to climb up the hierarchy and become bishops, which is forbidden for married priests.

Johnny Estephan, 22, is still undecided. “A father has a sense of responsibility, he knows what it is to get up at 2 a.m. to feed a baby. It prepares you to be in charge of a parish, but you have to be able to handle both,” he told Al-Monitor.

You must also be able to support your family. In Lebanon, a priest’s salary at roughly $400 a month is not enough. Therefore, priests often have another job.

After his ordination, Zeidan plans to resume his old job as a supervisor in a Christian school. He also dreams of having a second child.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

By Francis X. Rocca

Germany’s Catholic bishops will meet in Frankfurt on Thursday to launch their most ambitious effort yet in their role as the church’s liberal vanguard: a two-year series of talks rethinking church teaching and practice on topics including homosexuality, priestly celibacy, and the ordination of women.

Conservatives in Germany and abroad are greeting the prospect with alarm, and nowhere more so than in the U.S., whose episcopate has emerged as the western world’s foremost resistance to progressive trends under Pope Francis.

The tension between the groups epitomizes significant divisions in the church, which some warn could lead to a permanent split.

Earlier in January, a group of conservative Catholics from various countries, including Archbishop Carlo Maria Viganò, a former Vatican envoy to the U.S. who has become one of the pope’s harshest critics, gathered in Munich to warn that the German initiative would result in “the constitution of a church separate from Rome.”

The event starting this week originated as a response to the scandal over sex abuse of minors by Catholic priests. A 2018 report on the crisis in Germany called for a more positive attitude to homosexuality and more attention to the challenge of celibacy. Catholic women’s groups later prevailed on the gathering to also address the question of gender equity in the church’s leadership.

The decline of the Catholic Church in Germany has accelerated amid the scandals and growing secularization. According to the church’s latest statistics, 216,078 people left the church in 2018—a leap of 29% from the previous year. A poll published in January by the Forsa Institute showed that only 14% of Germans trusted the Catholic Church, down from 18% the previous year. Trust in Pope Francis fell to 29% from 34%.

However, the church in Germany is prospering as never before in material terms, receiving a record €6.6 billion ($7.3 billion) through a state-collected tax in 2018. German bishops are among the biggest financial supporters of the Vatican and of Catholic institutions in the developing world.

German bishops have enjoyed rising influence under Pope Francis, reflected in his policies of greater leniency on divorce and more autonomy for local church authorities on matters such as liturgy—moves long advocated by German theologians.

The leaders of the German synod, which will include representatives of Catholic laypeople, say they are offering it as a model for the church at large.

Ludwig Ring-Eifel, head of the German bishops’ news agency, estimates that around two thirds of the bishops—the threshold for passing a resolution—support the ordination of married men and women deacons and half are in favor of blessings for same-sex unions.

American conservatives say that for a branch of the church even to consider such moves poses a threat to unity.

“The German bishops continue move toward #schism from the universal Church,” Archbishop Samuel Aquila of Denver said on Twitter in September.

A minority of German bishops share such fears—and look to the U.S. for support. Cardinal Rainer Maria Woelki of Cologne, leader of the German conservatives, traveled last summer to the U.S., where he visited various church institutions and met with some of his most prominent American counterparts.

“Everywhere, I encountered concern about the current developments in Germany,” the cardinal later told his diocesan newspaper. “In many meetings, the worry was tangible that the ’synodal path’ is leading us on a German special path, that in the worst case we could even put communion with the universal church at risk and become a German national church.”

Pope Francis himself has cautioned the Germans not to stray too far.

“Every time an ecclesial community has tried to get out of its problems alone, relying solely on its own strengths, methods and intelligence, it has ended up multiplying and nurturing the evils it wanted to overcome,” the pope said in an open letter to German Catholics in June.

But after meeting with the pope and Vatican officials in September, Cardinal Reinhard Marx of Munich, chairman of the German bishops conference, said: “There are no stop signs from Rome.”

In fact, when Pope Francis has publicly entertained the possibility of a split in the church, it has been in regards to the U.S., not Germany.

“There is always the option for schism,” the pope said in September, in response to a reporter’s question about conservative American opposition to his agenda. “I pray that schisms do not happen, but I am not afraid of them.”

That lack of fear could be because only the pope can decide whether or not a state of schism even exists, said Adam DeVille, a professor of theology at Indiana’s University of Saint Francis.

“If things get too far out of hand one way or another, I can see him acting in extreme but selective cases,” to stop any separatist moves, Mr. DeVille said.

“All it would take would be the sudden forced ‘retirement’ of a couple especially outspoken or perceived troublemakers, in Germany or anywhere else, for the others to shut up, and fall docilely in line,” he added.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!