“I think it’s different for parents. We have to protect our children. That’s our No. 1 calling in life, and that comes before everything.”

By Julie Beck and Ashley Fetters

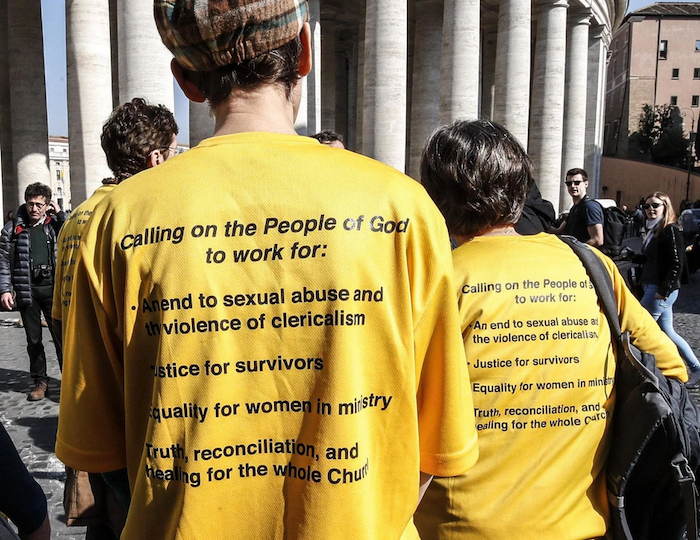

As it has been for decades, the Catholic Church is in the midst of a crisis, one whose long reach has traumatized thousands and left one of the world’s oldest institutions struggling to find a way forward. In late February, the Vatican held a high-profile conference on the sexual-abuse crisis—the revelations of decades of abuse, by priests in different parts of the globe, of children, adult seminarians, and nuns. During the conference, Pope Francis called for “concrete” change, though the Atlantic reporter Rachel Donadio wrote that, on the whole, the meeting seemed largely to be a “consciousness-raising exercise,” out of step with the “zero tolerance” that many victims’ advocates in the United States have been demanding for priests who use their power to abuse. It seems the crisis will likely drag on as the Church’s highest authorities continue their slow-moving reckoning.

What is an institutional crisis for the Church is a personal crisis for the faithful. Lay Catholics are left to grapple with what this crisis means for them, their families, and their faith. Parents in particular often feel acutely conflicted. How can they not worry about sending their children to be altar servers after reading about priests taking advantage of altar servers in the past? At the same time, devout parents who deeply love the Church naturally want their children to receive its spiritual benefits. What are they to do?

Some decide that they simply can’t reconcile their faith with decades of abuse and the subsequent cover-ups, or that the best way to protect their kids is to leave the Church. Laura Donovan, 30, says the child-sexual-abuse crisis is the reason she’s parted ways with the Catholic Church. Donovan, a social-media manager based in Los Angeles, had drifted away somewhat from her Catholic upbringing by the time The Boston Globe revealed the extent of the Catholic Church’s cover-up of Boston-area priests’ child abuse in 2002, but when she learned just how widespread the problem was, she says, “ultimately, that’s what made me think, I don’t want to go back to a Catholic church again, and I certainly don’t want to raise my own children in a religion like that.”

The Pennsylvania grand-jury report that revealed 70 years of abuse by more than 300 priests came out in August of last year, around the time Donovan’s first child, a son, was born. After becoming a parent, Donovan felt called back to Christianity and wanted to raise her family in a Church, but she and her husband “made the call not to raise him Catholic.”“

Eventually, Donovan’s son was baptized in the Lutheran Church, and Donovan herself was confirmed as well. Her husband grew up attending a Lutheran church, and when Donovan first attended with him, “I felt really comfortable there,” she says. “It had a lot of elements of what I like about the Catholic Church—it’s old, it’s structured, but it doesn’t have that big scandal, obviously.” Still, she misses some of the Catholic traditions she grew up with: the songs, the rosary beads, the congregational sign of peace, “praying to saints and thinking about angels.” Today, when Donovan prays, she has a hard time not instinctively making the sign of the cross.

It’s difficult to know just how many people have left the Catholic Church as a direct result of the sexual-abuse crisis. But across the United States, the Catholic Church is losing members at a faster rate than any other religion, with more than six former Catholics for every recent convert as of 2015, according to the Pew Research Center. (The second-fastest-declining religion in the United States was mainline Protestantism, with 1.7 former congregants for every new member.) From 2010 to 2016, the percentage of American adults who describe themselves as Catholic dropped from 25.2 percent to 23.5 percent. While it’s unclear whether the abuse crisis is the main reason Catholics are leaving the Church, a 2016 Public Religion Research Institute report found that people who were raised Catholic were more likely than those raised in any other religious tradition to characterize their departure as a direct result of “negative religious treatment of gay and lesbian people” and/or “the clergy sexual-abuse scandal.”

Other Catholic parents, though distressed by the Pennsylvania revelations and earlier reports on the crisis, are committed to the Church.

“It’s not something that changed my day-to-day practice of the faith, and I couldn’t see how it possibly could,” says Kendra Tierney, a 42-year-old writer and stay-at-home mother of nine children, ages 1 to 16 years old. “If you believe that the Catholic Church is the one founded by Jesus Christ, there is nowhere else to go. Jesus asked Peter, ‘Are you going to leave me also?’ and Peter says, ‘To whom shall we go?’ This is how I feel.”

She sees cases of abuse as “failings of personal holiness,” and rather than “sitting back and saying, ‘This is a terrible thing; this is a threat to my children and my faith,’” she wanted to do something in response to the news. Along with some others in the Catholic community online, Tierney launched a campaign to promote a month-long period of prayer, fasting, and sacrifice, as an act of reparation to God for the sins of abusive priests and the bishops who covered up their actions.

“For the whole month of September, our family observed kind of a Lent,” she says. “We gave up all treats, desserts, and sodas, all TV and video games, and we added in a special prayer from a book called In Sinu Jesu, a prayer of reparation for priests. We are all sinners, and if we can each improve as a member of the body of Christ, if I can raise holy sons and daughters, that’s going to help the Church.”

One Catholic father, a 35-year-old in New York City, seems to be feeling torn between raising a holy daughter and protecting her. (This man asked to remain anonymous, because he works for a Catholic organization and worried there could be consequences at his job if he spoke freely about the Church.) He grew up in a Hispanic Catholic family and went to Catholic school for middle and high school, and though he didn’t go to church much in college, he says he grew closer to the Church after he met his wife. “She was much more devout than me,” he says.

The man says he and his wife have not yet discussed how they feel about raising their daughter, now 2, in the Church, in light of the sexual-abuse crisis. “We’ve just been numb,” he says. Plus, with the stresses of parenting a 2-year-old, the family hasn’t had a ton of time to go to church lately anyway. “But I’m not going to deny that part of it is a real distaste for all this news that keeps coming out,” he says.

A couple of days after the Pennsylvania report was released, he posted on a Catholicism subreddit, asking whether it was reasonable to be wary “of priests with very poor social skills or [who] appear awkward?” In the replies, some people chided him, saying that just because someone is awkward doesn’t mean he’s a predator, but the man still feels like he needs to trust his gut if someone seems off to him.“I think it’s different for parents,” he says. “We have to protect our children. That’s our No. 1 calling in life, and that comes before everything. You’re not worried about the Church or school—you’re allowed to judge and be cautious and not feel guilty about that, because you’re a protector.”

Nonetheless, he still hopes to send his daughter to Catholic school when she’s older, and for the Church to be part of her life in some way, even if he’s still thinking through how exactly to handle it. “[Catholicism] is wrapped up in identity for a lot of Hispanics,” he says. “I want my daughter to find her own way, but there is a place in my heart that still hopes she ends up being part of the faith. There’s a lot of beauty in the Church. Even if you just want to look at Christ as a historical figure, that’s a great model for how people should treat other people.”

Among families who are still part of a Catholic church, some parents have begun to rethink the level of their children’s involvement in the church community. The Catholic dad in New York City, for example, said, “I probably would never feel comfortable with my daughter being alone at a church by herself without parents around.”

In 2018, after the Pennsylvania grand-jury report, Chris Damian, an author and attorney based in the Twin Cities in Minnesota, co-founded YArespond, a group that hosts events for young Catholic adults to get together and discuss the crisis in the Church. At a meeting in August, more than 100 attendees gathered in the basement of a Minneapolis church to express sentiments including worry, disillusionment, anger, and grief. According to Damian’s blog, one attendee said, “There’s no way I would let my child be an altar server.”

It’s an understandable position to take, says Kirby Hoberg, 28, a blogger, actor, and mother of three who helps YArespond organize and host meetings—especially given that, historically, altar servers have spent more time alone with priests than have other children in a congregation. “I hear that a lot, and I see why people would do that,” Hoberg says.

A dose of caution is enough to make some Catholic parents comfortable with their kids being involved in church activities. Chris Mayerle’s 12-year-old son, for instance, not only is an altar server but knows how to serve Mass in Latin, which apparently makes him in quite high demand in their home state of Utah. The Mayerles—Chris, his wife, and their seven children (some of whom are adults)—have moved around a good amount, since Chris was in the Air Force for a time. In each place they’ve lived, they’ve vetted churches and priests—“parish shopping,” as he puts it—before settling down with a congregation.

“We became very, very selective about which priests we would be around, and which priests we would let our children be around,” Mayerle says. “Everywhere we’ve been, we’ve been close to our priests. We have them over for dinner. You can get a sense when things are not quite right with a priest. But we never put our kids in a situation where they’ve been alone with a priest or where they could be compromised.”

The way a priest says Mass, Mayerle believes, is one clue to his personality, and that plays a role in whether or not Mayerle will trust him. At the first church the family went to in Utah, “the priest just skipped over major parts of the Mass,” he says. “That was off-putting to us. One of the things we look for is when they do things the way they’re supposed to. In other words, they’re obedient—it means they’re probably obedient to their vows also. When they just start winging it, it means they view themselves as their own authority, which I don’t think is healthy.”

Of course, many Catholic parents, while dismayed by how the scandal reflects on the Church as an institution, still trust their own parishes and priests. They say their churches have routine audits, training for adult volunteers, and policies that prohibit priests from being alone with children. Some Catholic parents we spoke to mentioned that their priests openly discuss the issue and share in their grief, and that the leaders in their churches seem willing to engage with parishioners in discussions on how to make Catholic churches safer places. Others emphasize that they believe the vast majority of priests are morally sound leaders, and that only a small portion have been accused of inappropriate conduct.

But perhaps the biggest change from earlier eras, when some of the abuse described in the Boston and Pennsylvania reports occurred, is that for some of today’s Catholic families, priests are not put on a pedestal. Several parents we spoke to for this piece said there is less of a sense among Catholics today than in decades past that priests are infallible, or more incorruptible than the average person. And so they teach their kids to be wary of inappropriate behavior from all grown-ups—priests and other spiritual leaders included.

“You want your kids to have respect for people in positions of authority, but perhaps overemphasized respect for the clergy allowed this culture of abuse to last in the shadows as long as it did,” Tierney says. “They’re not superheroes; they are humans. We are all capable of sin, and that’s the conversation I’ve had with my kids. You trust your gut, and if something doesn’t feel right, it probably isn’t.”

“It’s not that I would treat my priest differently from the way I would another grown-up, but I am very, very cautious about leaving my children alone with anyone,” says Haley Stewart, the writer behind the Catholic blog Carrots for Michaelmas and a 33-year-old mother of four in Waco, Texas. Her children are seven months, 5, 7, and 10, and she says she has talked about bodily autonomy with them from a young age.

“We start really young by teaching our kids the anatomical names of their body parts, saying, ‘This part of your body is not for anyone else to touch,’” she says. “It doesn’t have to be a big scary conversation with a small child. Also impressing upon them that if someone ever does something to your body that you did not like, that is not your fault, and you need to tell Mom and Dad so we can make sure you are safe from that person.”

Kirby Hoberg has noticed that the younger Catholic parents she knows seem angrier about the recent wave of sexual-abuse revelations than do older parents she knows who were adults during the first phase of the crisis, in 2002. “I think I was turning 12 when the news started to break … We watched things like the Dallas Charter [come into effect] and really believed that things were being taken care of,” she says. “I’m noticing a lot of people older than me [seem to feel] very helpless. Like, ‘We tried once, and now it’s gone.’”

Hoberg expects that Catholic parents of her generation will be reckoning with the aftereffects of the sexual-abuse crisis for years to come. “It’s going to be a long road,” she says. “The kids aren’t going away, and these questions are only going to get harder [as they get older].”

She’s uncertain, she adds, about how she might handle a future in which her son decides he wants to go to seminary—a sentiment that Chris Mayerle, the Utah dad whose son is an altar server, echoes. His son has expressed interest in becoming a priest, and if he were to follow through, Mayerle says, “we’d be excited, in all honesty. The Church is in great need of renewal, and it’s gotta start somewhere. But whatever seminary he wanted to go to, we would vet very closely.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!