It took Bruce Novozinsky more than seven years and 14,000 pages of letters, memos, manuscripts and interviews to produce his book on the decades of sexual abuse allegedly covered up by the powers that be in the Roman Catholic Church.

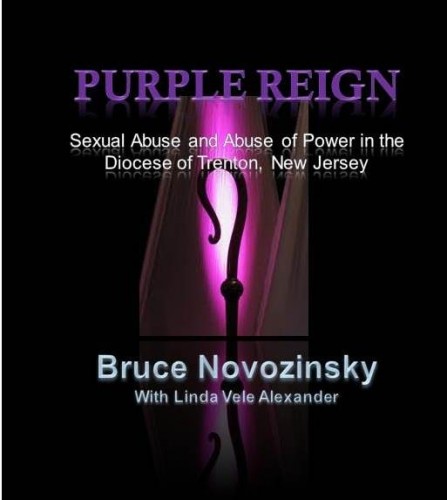

“Purple Reign: Sexual Abuse and Abuse of Power in the Diocese of Trenton”, written with co-author Linda Vele Alexander, hit stores and online in June and recently became the sixth-most purchased e-book about Christianity on Amazon.com.

“Purple Reign: Sexual Abuse and Abuse of Power in the Diocese of Trenton”, written with co-author Linda Vele Alexander, hit stores and online in June and recently became the sixth-most purchased e-book about Christianity on Amazon.com.

“Purple Reign,” the result of what the Upper Freehold resident calls an “obsession,” chronicles his memoirs in Catholic school — and three years at the former Divine Word Seminary in Bordentown — and the sexual abuse suffered in the Diocese of Trenton through the mid- to late 20th century.

“We were all products of the 1970s, where you just kind of prayed to, obeyed and paid the church. Nobody ever questioned the politics involved,” Novozinsky said in a telephone interview earlier this week.

The book reads like a conversation with Novozinsky — “I write like I speak and that’s with candor and very little filtering,” he writes. The book is interspersed with firsthand accounts of others’ sexual abuse, correspondence with the alleged perpetrators more than 40 years later, and reflections on the abuse perpetrated by men wholly trusted by their victims.

“I didn’t look like the typical candidate for a kidnapping, or a sexual assault for that matter, and yet less than an hour before, I had a priest on top of me,” Novozinsky writes of his own close call with sexual abuse by his parish priest decades ago.

He latched onto the subject when news broke of the sexual abuse scandal 10 years ago in the Archdiocese of Boston, as those experiences and rumors started “eating at him.”

“To say that the Catholic Church abuse crisis started in January 2002 in Boston, Mass., is naive and simply not true,” Novozinsky writes. “Sexual abuse and the abuse of power in the Church have been around since Adam bit the apple.”

The book includes anecdotes of weeping parents pleading with priests to take action over the abuse witnessed by their sons — and the resulting inaction.

“Everybody had a horrible, horrible story to relay, but the common theme was, ‘Nobody did anything about it,’ ” Novozinsky said. “Or they settled a case and were told to be quiet, or were told, ‘This is a secret between us and God.’ Just being in a workforce and in corporate America, it just dawned on me that this is the highest degree of sexual harassment.”

“The abuse is bad enough. It’s horrid,” Novozinsky said. “But the cover-up is worse, as far as I’m concerned.”

Many of the alleged perpetrators — who he said were never charged due to a “loophole” in the legal system — still live in the area, still wearing priest collars.

Even Novozinsky’s attempted abuser lives “scot-free,” he said.

The Diocese of Trenton declined to comment on any of the allegations made in “Purple Reign.”

“We have nothing to say about this book,” spokeswoman Rayanne Bennett said in a statement. “Regarding the overall issue, the diocese has been proactive and diligent in the steps we’ve taken to protect children and assist victims. Our efforts have been pastoral and transparent and we take our responsibilities in this matter very seriously.”

Novozinsky said parents, though, have ramped up efforts to protect children.

“People today are so aware that if one accusation was made, the school would be shut down,” Novozinsky said. “People are much more in tune and sensitive to it.”

The sex abuse scandal and the cover-up his book alleges hasn’t shaken Novozinsky’s faith at all, he said. His children even attend Catholic schools.

“My faith is my faith in God and the Roman Catholics. I will always be a Roman Catholic. (The research) has made my faith stronger for me,” Novozinsky said. “However, the hierarchy of the Catholic Church, from Trenton to Rome — I have absolutely no confidence in them.”

Complete Article HERE!