Allow me to call you attention to another brilliant commentary posted over at Enlightened Catholicism:

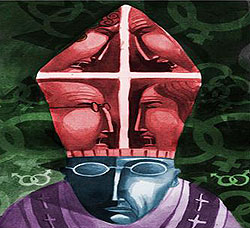

What kind of pope do Roman Catholics need?

By Cristina LH Traina

Selection of the next Pope will factor in a host of complicated variables as wings of the Church compete for ascendancy.

Pope Benedict XVI’s impending resignation has already fuelled all the usual speculation about candidates for his successor, accompanied by profiles, photos and odds of election. Behind the hoopla is the question, what sort of leader will really be best for the Church?

Pope Benedict XVI’s impending resignation has already fuelled all the usual speculation about candidates for his successor, accompanied by profiles, photos and odds of election. Behind the hoopla is the question, what sort of leader will really be best for the Church?

Benedict’s own admission that an elderly man cannot undertake the globe-trotting that effective relations require suggests that as a rule, a younger, healthier leader would be a wise choice. But the Church also faces the question what style of leadership would be most fruitful.

Despite the vision of Vatican Council II, which recommended collegial authority and granted the laity almost complete province over action in the world, Pope John Paul II’s and Pope Benedict XVI’s pontificates have echoed an ultramontane, top-down model in which the authority of the pope supersedes that of the bishops, individually or in national organisations.

History of papal power

Vatican I ratified the ultramontane model in an era in which the Roman Catholic Church felt besieged on all sides. The Church had just lost the Papal States and suffered long periods of anti-clericalism and persecution in Europe. The Council responded by absolutising the popes’ control over the one thing left to them: the Church. Over the next 50 years, popes declared a single standard of orthodoxy (the works of Thomas Aquinas) and published – and enforced – laundry lists of anathematised philosophical and political beliefs.

In earlier periods, strong central control could not be realised so easily in practice, except in cases like the Inquisition in which civil power could be conscripted. But when travel took place on foot, by horse, or by sailing ship, and all communications were carried by letter, people had to choose carefully what information to send up and down the chain of the hierarchy. Practices varied, and many “irregularities” simply went uncommented.

Flash forward to the present day, and ultramontanism becomes a little less forgiving. Photos, news reports and blog posts make their way across oceans in seconds or less. Not only does Rome have theoretical authority over every Catholic person and organisation, it has actual access to real-time information about them. This is not to belittle the silencings, excommunications, and even executions of earlier eras, or to overlook the inefficient contemporary Vatican bureaucracy, in which branches famously work at cross purposes. But strong central control combined with instant communication from every layer of the church in every corner of the world creates unprecedented micro-managerial possibilities.

Contemporary contradictions

Cue the debate over the next pope. So-called “conservative” Catholics will be cheering for a candidate who  continues Benedict’s line of strong Catholic identity. Conservatives, so the stereotype goes, will want a firm hand guiding a centralised, top-down hierarchy capable of overseeing of theology and charitable work all over the world. The ultramontane trend confirmed at Vatican I, and alive and well in the CEO model of the papacy, is their ideal.

continues Benedict’s line of strong Catholic identity. Conservatives, so the stereotype goes, will want a firm hand guiding a centralised, top-down hierarchy capable of overseeing of theology and charitable work all over the world. The ultramontane trend confirmed at Vatican I, and alive and well in the CEO model of the papacy, is their ideal.

A look back at Pope Benedict XVI’s career

In contrast, conventional wisdom says that so-called “liberal” Catholics will be hoping for a candidate who, like John XXIII 50 years ago, might surprise the world by changing direction. Liberals will want a decentralised, participatory structure that places most power in the hands of national bishops’ conferences, in collaboration with the laity. On this view, popes are good for inspiration, pastoral care and ecumenical diplomacy but too far removed from the local details of daily life to rule sensitively on regional questions.

Recent events seem to reinforce these stereotypes. Liberal Catholics took it amiss when the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (CDF) undertook a comprehensive review of the Leadership Conference of Women Religious, the largest organisation of Catholic women major superiors. The CDF judged that rampant “radical feminism”, dissent and collaboration with questionable social justice organisations needed correction, and it appointed Seattle Archbishop Peter Sartain to oversee the “renewal” of the organisation.

Liberals viewed this as an attempt to silence the most educated and independent branch of American women religious. Conservatives held up the smaller Council of Major Superiors of Women Religious, which was not investigated, as an example of fidelity and obedience.

Similarly, when Benedict blocked Lesley Anne Knight’s run for a second term as director of the Catholic umbrella organisation Caritas Internationalis and issued his motu proprio on preserving the Catholic identity of Catholic charities, liberals fretted over Catholic groups’ losses of funds and of opportunities for collaboration with independent non-profits. Conservatives, on the other hand, heralded the increased oversight as an overdue means of ensuring the purity of Catholic teaching and of income streams.

The important exception seems to be the clerical sex abuse crisis. Here organs associated with American liberal Catholicism – Voice of the Faithful, The Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests, Call to Action, BishopAccountability.org, the National Catholic Reporter and others – have echoed conservatives in demanding authoritative, decisive action from the Vatican against bishops who facilitated and hid priestly sexual abuse. Catholics in Ireland and much of Europe, not to mention other parts of the world, have joined them in this demand.

Demand for clerical accountability

And here’s the contradiction. Catholics may not be able to have their cake and eat it too. Some conservative laypeople have laid aside ultramontanism to join the liberal demand for clerical accountability to laypeople, and liberals have joined the conservative chorus requesting action from Rome. Only a tough, centralised hierarchy that monitors all of its outposts carefully can take the strong action against bishops that liberal Catholics seek. A truly collegial model – perhaps a federation of strong national churches with a single spiritual leader, as in the Anglican Communion – would yield more adaptability at the local level but would not have the central power to depose transgressing bishops.

Thus liberal Catholics face a quandary. A pope strong and authoritative enough to purge transgressing bishops is likely to use his power as well to purge liberal theologians, nuns and clergy. A pope who opts for a collegial style more in keeping with Vatican Council II’s precedent will have to rely on his fellow bishops to monitor each other, something they have so far shown little willingness to do.

Conservatives face a similar quandary. What will ensure that the strong hierarchy they envision protects laypeople from clerical transgressions?

There is a third option, of course. If the Catholic Church had structures of accountability that operated from below rather than from above, it would not need to rely on benevolent ultramontanism to get rid of destructive bishops. The next pope could undermine the Vatican’s managerial authority even more radically by insisting that bishops share power collegially with priests, vowed religious and laypeople, and by instituting term limits for bishops like those observed by many Protestant communions. Benedict XVI’s resignation could be the precedent. Stranger things have happened.

Complete Article HERE!

Cardinal Mahony used cemetery money to pay sex abuse settlement

By Harriet Ryan

The Archdiocese of L.A. took $115 million from its cemeteries’ maintenance fund in 2007, nearly depleting it. The move seems legal, but it was not announced, and relatives of the dead were not told.

Pressed to come up with hundreds of millions of dollars to settle clergy sex abuse lawsuits, Cardinal Roger M. Mahony turned to one group of Catholics whose faith could not be shaken: the dead.

Under his leadership in 2007, the Archdiocese of Los Angeles quietly appropriated $115 million from a cemetery maintenance fund and used it to help pay a landmark settlement with molestation victims.

Under his leadership in 2007, the Archdiocese of Los Angeles quietly appropriated $115 million from a cemetery maintenance fund and used it to help pay a landmark settlement with molestation victims.

The church did not inform relatives of the deceased that it had taken the money, which amounted to 88% of the fund. Families of those buried in church-owned cemeteries and interred in its mausoleums have contributed to a dedicated account for the perpetual care of graves, crypts and grounds since the 1890s.

Mahony and other church officials also did not mention the cemetery fund in numerous public statements about how the archdiocese planned to cover the $660-million abuse settlement. In detailed presentations to parish groups, the cardinal and his aides said they had cashed in substantial investments to pay the settlement, but they did not disclose that the main asset liquidated was cemetery money.

In response to questions from The Times, the archdiocese acknowledged using the maintenance account to help settle abuse claims. It said in a statement that the appropriation had “no effect” on cemetery upkeep and enabled the archdiocese “to protect the assets of our parishes, schools and essential ministries.”

Under cemetery contracts, 15% of burial bills are paid into an account the archdiocese is required to maintain for what church financial records describe as “the general care and maintenance of cemetery properties in perpetuity.”

Day-to-day upkeep at the archdiocese’s 11 cemeteries and its cathedral mausoleum is financed by cemetery sales revenue separate from the 15% deposited into the fund, spokeswoman Carolina Guevara said. Based on actuarial predictions, it would be at least 187 years before cemeteries are fully occupied and the church started to draw on the maintenance account, she said.

“We estimate that Perpetual Care funds will not be needed until after the year 2200,” Guevara wrote in an email.

The church’s use of fund money appears to be legal. State law prohibits private cemeteries from touching the principal of their perpetual care funds and bars them from using the interest on those funds for anything other than maintenance. Those laws, however, do not apply to cemeteries run by religious organizations.

Mary Dispenza, who received a 2006 settlement from the archdiocese over claims of molestation by her parish priest in the 1940s, said her great-uncle and great-aunt are buried in Calvary Cemetery in East L.A.

“I think it’s very deceptive,” she said of the way the appropriation was handled. “And I think in a way they took it from people who had no voice: the dead. They can’t react, they can’t respond.”

The fund dates to the tenure of Bishop Francis Mora, who opened Calvary in 1896. An official archdiocese history published in 2006 recounts how the faithful of Mora’s era were assured their money was “in the custody of an organization of unquestionable integrity and endurance” — the Catholic Church.

Over the next century, the archdiocese built more cemeteries, and each person laid to rest meant a new deposit into the maintenance account. By the time of the sex abuse settlement, there were cemeteries from Pomona to Santa Barbara and $130 million in the fund. Church officials removed $114.9 million in October 2007.

Complete Article HERE!

Experts: Top 5 picks for the next pope

Three expert Vatican watchers list some of their leading papabile – Italian for cardinals who might be elected as the next pope. In alphabetical order:

Cardinal Angelo Bagnasco, Archbishop of Genoa, made headlines last year for a ripping attack on then-Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi and other Italian leaders as unethical role models.

Cardinal Angelo Bagnasco, Archbishop of Genoa, made headlines last year for a ripping attack on then-Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi and other Italian leaders as unethical role models.

He’s “fairly savvy about both secular politics and the media,” writes National Catholic Reporter Vatican specialist John Allen.

Church historian Matthew Bunson, calls Bagnasco, 69, former professor of metaphysics and contemporary atheism “an intellectual heavyweight” who speaks multiple languages, and takes strong stands on doctrine.

But the biggest boost may come from Bagnasco’s role as two-time president of the Italian bishops conference. Italians hold about a fourth of the seats in the College of Cardinals that will choose the next pope.

Cardinal Marc Ouellet, the Canadian-born former Archbishop of Quebec, now heads the powerful Congregation of Bishops, a “great spot for great spot for making friends and influencing people,” by choosing the global leadership of the Church, says Allen. He describes Ouellet, 68, as a veteran in dealing with the secularized West, someone smart and intellectual with “a cosmopolitan resume,” says Allen.

Cardinal Marc Ouellet, the Canadian-born former Archbishop of Quebec, now heads the powerful Congregation of Bishops, a “great spot for great spot for making friends and influencing people,” by choosing the global leadership of the Church, says Allen. He describes Ouellet, 68, as a veteran in dealing with the secularized West, someone smart and intellectual with “a cosmopolitan resume,” says Allen.

Ouellet is close to the late pope in theological thinking and someone who could bring a strong hand to the curia (the Vatican bureaucracy).

“The electors could get a traditional pick still say, ‘Hey, we’re innovators. We went to North America!’ He’s the eye-popping choice.” says David Gibson, author of several books on the Catholic Church including a biography of Pope Benedict XVI.

Cardinal Gianfranco Ravasi, elevated to cardinal in 2010 and head of the Pontifical Council for Culture, is so smart, says Allen, “if you were picking a quiz bowl team in the College of Cardinals, most people would start with Ravasi.”

Cardinal Gianfranco Ravasi, elevated to cardinal in 2010 and head of the Pontifical Council for Culture, is so smart, says Allen, “if you were picking a quiz bowl team in the College of Cardinals, most people would start with Ravasi.”

Allen calls him “a master communicator who could take the world by storm. He can ignite rich, solid commitment to Catholic orthodoxy without ever coming off as a scold.”

The Italian-born Biblical scholar has the advantage of being based in Rome. Cardinals in the curia, the church’s governing bureaucracy, get to meet many of the electors that cardinals in far-flung posts scarcely know.

Still, Allen sees hurdles for Ravasi, who, at age 69 has never been a diocesan bishop. “Some would wonder if there were substance beneath the charm. He spends a lot more time talking to the outside world than within the church. Some see him as trying too hard. That’s off-putting.”

Cardinal Leonardo Sandri, 70, the head of the Vatican’s office for the Eastern Catholics and a longtime Vatican diplomat, would be the first pope from South America, the center of global Catholicism today, if he were chosen.

Cardinal Leonardo Sandri, 70, the head of the Vatican’s office for the Eastern Catholics and a longtime Vatican diplomat, would be the first pope from South America, the center of global Catholicism today, if he were chosen.

“He’s prayerful, well-liked around the world and very much aware, because of his diplomatic experience, of the global dimensions of the Church,” says church historian Matthew Bunson.

He may be best known in his role as No. 2 in the Vatican Secretary of State’s office. Sandri was the person who read the public announcement that Pope John Paul II had died in April 2005.

However, Sandri’s age, his lifelong background in the church bureaucracy, and his reserved demeanor may work against him, says Bunson.

Cardinal Angelo Scola, Archbishop of Milan, leads Bunson’s list as “an Italian with the intellectual chops for the job” who would bring Benedict’s enthusiasm for “recapturing Catholic excitement in Europe.”

Benedict moved him from another high profile post, Venice, in July, 2011, thereby giving this Vatican insider a perch at Europe’s largest diocese. Milan and Venice together have produced five popes in the last 100 years.

A top scholar on Islam and Christian-Muslim dialog, Scola, 70, is “well positioned for dealing with the challenges of secularism and materialism in the West,” says Bunson.

Scola once said: “Our job now has to be to help people to remember God. People suffer from a kind of amnesia about God and we have to remind them to reawaken God in their hearts and in their minds.”

Complete Article HERE!

Pope resignation: Full text

Pope Benedict XVI has announced his resignation. Here is the full text of his statement from the Vatican translated from the Latin:

Dear Brothers,

I have convoked you to this Consistory, not only for the three canonisations, but also to communicate to you a decision of great importance for the life of the Church.

I have convoked you to this Consistory, not only for the three canonisations, but also to communicate to you a decision of great importance for the life of the Church.

After having repeatedly examined my conscience before God, I have come to the certainty that my strengths, due to an advanced age, are no longer suited to an adequate exercise of the Petrine ministry.

I am well aware that this ministry, due to its essential spiritual nature, must be carried out not only with words and deeds, but no less with prayer and suffering.

However, in today’s world, subject to so many rapid changes and shaken by questions of deep relevance for the life of faith, in order to steer the boat of Saint Peter and proclaim the Gospel, both strength of mind and body are necessary, strength which in the last few months, has deteriorated in me to the extent that I have had to recognise my incapacity to adequately fulfil the ministry entrusted to me.

For this reason, and well aware of the seriousness of this act, with full freedom I declare that I renounce the ministry of Bishop of Rome, Successor of Saint Peter, entrusted to me by the Cardinals on 19 April 2005, in such a way, that as from 28 February 2013, at 20:00 hours, the See of Rome, the See of Saint Peter, will be vacant and a Conclave to elect the new Supreme Pontiff will have to be convoked by those whose competence it is.

Dear Brothers, I thank you most sincerely for all the love and work with which you have supported me in my ministry and I ask pardon for all my defects.

And now, let us entrust the Holy Church to the care of Our Supreme Pastor, Our Lord Jesus Christ, and implore his holy Mother Mary, so that she may assist the Cardinal Fathers with her maternal solicitude, in electing a new Supreme Pontiff.

With regard to myself, I wish to also devotedly serve the Holy Church of God in the future through a life dedicated to prayer.

Complete Article HERE!