By David Heinzmann

When the pastor of Ottawa’s Catholic parishes announced in March that his assistant, the Rev. Jeffrey Windy, was being removed from ministry, the abrupt and mysterious departure came as a shock to people who had grown to like the young priest over the last nine months.

To others, the brief notice of the removal in the local newspaper brought a different kind of shock — that Windy had been serving as a priest at all.

He was, after all, an ex-con who had been arrested while assigned to a different parish in 2002 and served time in federal prison for manufacturing and selling gamma-hydroxybutyrate, more commonly known as GHB, or the date-rape drug.

Despite Windy’s criminal past, the bishop in Peoria had decided in 2013 to return Windy to parish work, first in Bloomington and then in Ottawa, just a few minutes from Windy’s hometown of Peru. Now he was being removed from ministry again — and the church wasn’t saying why.

People in the central Illinois towns of Ottawa, LaSalle-Peru and a handful of smaller communities that hug the banks of the Illinois River were left to wonder what had happened.

In fact, the explanation does not fit neatly into the usual narrative of priest misconduct. Late last winter, Windy’s superiors in Peoria learned that Windy had involved himself in a criminal court case, paying a visit to an 82-year-old crime victim along with the father of the woman who had robbed her. That man later would be charged with attempted harassment of the victim.

Windy’s role in the matter drew the attention of Ottawa police, who eventually showed up at church to question both the priest and his boss, the Rev. David Kipfer.

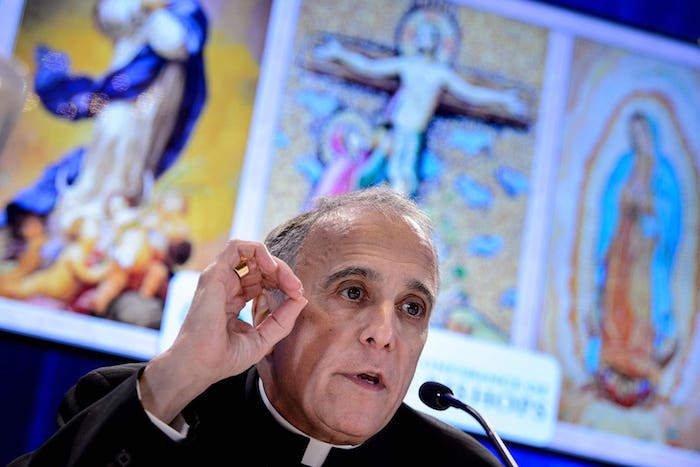

Within a few days, Peoria Bishop Daniel Jenky removed Windy from ministry, setting off a scramble among the priest’s supporters in Ottawa. At the request of a lawyer who is helping Windy, the LaSalle County state’s attorney and at least one other lawyer involved in the case wrote letters to Jenky explaining that the priest was not facing criminal charges. But the bishop has not changed his mind.

Windy declined to comment on his situation, but the prominent Ottawa-area lawyer advising him — former LaSalle County State’s Attorney Gary Peterlin — said the diocese is seeking to remove Windy from the priesthood permanently. Peterlin said the priest has done nothing that would justify removing him from ministry.

Jenky’s vicar general, Monsignor James Kruse, confirmed that Jenky has filed a canon law case in Rome seeking further action on Windy’s status. The fact that Windy did not seek the counsel of superiors in Peoria before involving himself in the criminal case, nor immediately report the police interview to the chancery, showed Windy had not overcome “a pattern of imprudence” that had marred his behavior for years, Kruse said.

Jenky “was immediately unnerved by the fact that he did not know about it,” Kruse said.

The bishop’s position is a turnaround from a decade ago, when Jenky repeatedly supported Windy’s efforts to win early termination of his parole. Jenky twice supported efforts to move Windy out of the Peoria Diocese so he could re-enter ministry away from central Illinois, where the “negative implications” of his date-rape drug conviction would be less of an issue, according to federal court records.

At a time when the public spotlight is again fixed on how the Catholic clergy deals with misconduct in its ranks, Windy’s case raises questions about how, when and with what oversight the church decides to return troubled priests to ministry, regardless of the nature of their transgressions.

“It’s amazing he was put back in,” said Terry McKiernan, president of BishopAccountability.org, a Boston-based advocacy group that has tracked the Catholic hierarchy’s record in dealing with priest misconduct. The fact that Windy has now been removed again “does seem to indicate that the diocese had not thought it through.”

Kruse said years of thought went into the decision to give Windy another chance after his conviction and drug-related problems.

“There was a probationary period to see if he was in a position to reintegrate into ministry,” Kruse said. Ultimately, diocesan officials felt as though Windy deserved compassion and had earned a chance. No one had ever alleged sexual misconduct of any kind, Kruse noted, and “with his addiction … it was something that had been overcome.”

The Peoria Diocese initially declined to comment to the Tribune, maintaining that the situation was a private personnel matter. Jenky agreed to allow Kruse to respond after the Tribune said the newspaper was going to write about the case regardless, based on documents and lawyers’ statements.

‘A terrible mistake’

In early 2002, Windy was a 31-year-old pastor running two parishes in tiny farming towns an hour north of Peoria. Young and athletic, he was popular with parishioners and often seen lifting weights in the garage of the parish house. That image was shattered when Windy was arrested in late January 2002 on federal drug charges.

The U.S. attorney’s office in Iowa alleged that Windy and five men from the Quad Cities had been manufacturing and selling GHB. Windy ordered chemicals and used church property to mix the drug, according to federal prosecutors.

At the time of their arrest, Windy and his codefendants said they were using the drug primarily as a bodybuilding supplement. However, the science underlying its purported muscle-building qualities is dubious at best, experts said.

“Is it legit? No,” said Mark Rasenick, a professor of physiology, biophysics and psychiatry at the University of Illinois at Chicago. “It is the fabric of urban legend. When you take GHB — it’s sedating. If you sleep well, you make more human growth hormone. And bodybuilders are known to inject human growth hormone. None of this has ever been proven to work.”

During his sentencing hearing, Windy acknowledged that he was addicted to the drug, which produces feelings of euphoria and relaxation as well as drowsiness. As Windy began to read a statement asking the judge for leniency, he broke down crying and asked his attorney to read what he had written, according to a transcript of the hearing.

“I know I have made a terrible mistake in using drugs and in purchasing the chemicals for the manufacturing of the same,” Windy wrote. “I have shamed my family, my parish, my brother priests and the lives that I have touched.”

The judge sentenced Windy to 70 months in federal prison, citing abuse of a position of trust as an aggravating factor. The priest spent four years in prison and was released on Dec. 12, 2006, according to court records. He then was subject to an additional three years of mandatory supervised release, the federal version of parole. Church officials said he underwent further counseling and evaluation.

In summer 2008, Windy began to ask the court to end his parole early so he could serve as a priest outside Illinois, first as a military chaplain and then, when that did not come to pass, as a parish priest in Brooklyn, N.Y. In a series of motions, his lawyer noted that the church was in need of his services because of “a worldwide shortage of priests.”

The motions acknowledged that “since his release from custody, his superiors have been reluctant to assign him to public pastoral duties, so as to avoid the negative implications associated with this pending case.” The court filings also stated that Bishop Jenky supported Windy’s efforts to rejoin active ministry elsewhere.

The Brooklyn appointment fell through “at the last minute,” Kruse said, when Windy “demonstrated some point of imprudence. It had to do with some things on his Facebook page.”

Kruse did not explain further. Windy’s Facebook posts over the years have mixed pastoral and religious messages with selfies from vacations and restaurants, often with a cocktail in hand.

Windy did not rejoin active ministry until he was placed in a Bloomington parish in 2013.

He served there for four years before transferring to Ottawa in June 2017 to serve three combined parishes — St. Patrick’s, St. Columba and St. Francis of Assisi — close to his hometown of Peru. In Ottawa he reconnected with old friends and relatives and gained supporters who liked his homilies and outgoing demeanor. But while Windy was getting settled, the trouble that would eventually reach him was growing.

‘No, he’s done’

A year ago, in October 2017, a 33-year-old woman named Deanna Rowley told an elderly couple outside an Ottawa steakhouse that she would open the door for them, according to police. As the 82-year-old woman passed by, Rowley grabbed her purse and tried to run. The woman struggled with her, and Rowley grabbed a wallet from the bag, jumped into her van and drove off.

Rowley eventually pleaded guilty to aggravated robbery of an elderly person and hoped to be placed in a drug treatment program. However, prosecutors were seeking a 12-year prison sentence.

This is where Windy entered the picture.

Rowley’s lawyer, Matthew Mueller, wanted to appeal to the elderly victim to make a statement supporting leniency, according to a letter he later wrote to Jenky in support of Windy. However, Mueller was concerned about reaching out directly for fear of intimidating the woman, he wrote.

Mueller relayed his concerns to Rowley’s father, Gary, the letter said. A few days later, Windy called Mueller to say that Gary Rowley, a parishioner at St. Patrick’s, had contacted him about the matter. The priest also asked “if it was illegal or even frowned upon” for him to reach out to the victim, according to the letter.

Mueller assured him it was common practice for a defense team to seek the support of the victim. According to Peterlin, Windy then went to see the victim at her home and Gary Rowley went with him, in a separate car.

The elder Rowley has a significant criminal history. Among his previous cases was a 2009 conviction for unlawful use of a weapon by a felon. He also had been charged with a felony for allegedly assaulting a pregnant woman.

After Windy talked to the elderly woman and introduced her to Gary Rowley, she called Mueller and, as the lawyer relayed in his letter, “indicated she did want to talk to me about the case and that she understood I was Deanna Rowley’s attorney. She expressed many good things about Father Windy.”

On Feb. 23, Gary Rowley was arrested and charged with felony attempted harassment of a witness, according to a statement from the Ottawa Police Department. “Rowley is accused of taking a substantial step in contacting a victim in a pending legal proceeding, being the robbery case of his daughter Deanna Rowley, with the intent to harass or annoy the victim,” it said.

Rowley’s attempted harassment case, as well as his felony assault charge, are scheduled for trial in January, prosecutors said.

As police investigated the allegations against Rowley, they questioned both Windy and the pastor, Kipfer.

LaSalle County State’s Attorney Karen Donnelly, whose office prosecuted Deanna Rowley, said she received a phone call from the Peoria Diocese’s top lawyer, Patricia Gibson, after the priests were questioned, asking if she was going to press charges.

Donnelly said she told Gibson “there was not enough to justify charges.” Only Gary Rowley would be charged with trying to intimidate the elderly woman, she said.

Windy was removed from ministry anyway. As parishioners mounted an effort to help him, Peterlin approached Donnelly and asked if she would state her position on the case in a letter to the bishop, Donnelly said. She ended up writing a second letter after the first had no effect on Windy’s status.

“Father Jeffrey J. Windy has never been considered for possible arrest in regard to his interaction with the victim,” Donnelly wrote in the second letter, dated April 28. “At no time was this office asked to pursue charges against Father Windy.”

Cathy Ciszweski, a retired nurse who attends St. Francis of Assisi parish, wrote a stern letter to the editor of the local paper in which she addressed Jenky directly, asking: “You have chosen to crucify Rev. Windy for what may I ask?”

She pledged to withhold her annual donation to the diocese until the bishop reinstates Windy. “He is a very good priest, in spite of what happened to him years ago,” she said in an interview. “I feel that he’s used that experience to be helpful.”

Kruse said the letters from Donnelly and others were beside the point.

“The fundamental reason Father Windy was removed was because of his tremendous lack of pastoral prudence in that he didn’t first contact the diocese when he first became involved in the Rowley case,” Kruse said. “That’s the reason the bishop said, ‘No, he’s done. He’s out.’”

Peterlin said he objects to the way the diocese keeps leaning on that one term.

“They can make their decision, but they should not be arbitrary decisions,” Peterlin said. “To come up with this ‘imprudent’ … that’s a judgment call. What I can see is that we’ve got some real overkill here on the part of the diocese.”

Kruse said that the day after the bishop learned of the police interview “we met with Windy and talked with him about the conversation with the police, and talked about all of the details.

“In general, let’s say he confirmed everything, and he said, with some sadness and distress, ‘Yes, I was very imprudent.’”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!