By

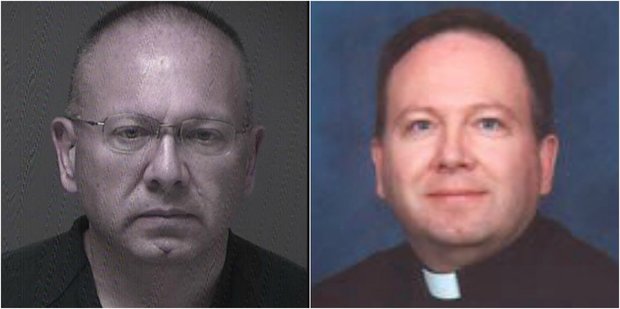

Thirteen years ago, amid allegations he molested a 16-year-old boy, the Rev. Kevin Gugliotta was suspended from ministry in New Jersey, his case referred to the Vatican for guidance because of an unusual circumstance.

When the alleged sex assaults occurred in the mid-1980s, Gugliotta wasn’t yet an ordained Catholic priest. He was a private-sector engineer and Boy Scout leader.

In the eyes of the Vatican, the distinction appeared to be a critical one, regardless of the case’s merit.

A spokesman for the Archdiocese of Newark told NJ Advance Media last week the Vatican ruled that church law, known as canon law, prevented Gugliotta from being punished for something he might have done as a layman. In December 2004, he was quietly reinstated, free of restrictions on his ministry, and served for years in various parishes, including a long stint as chaplain to a youth group.

That decision, which was not widely disclosed, is now being questioned by his accuser and others in the wake of Gugliotta’s arrest in October on 40 counts of possessing and disseminating child pornography.

Gugliotta, 54, remains jailed in Pennsylvania in lieu of $1 million bail, a spokeswoman for the Wayne County District Attorney’s Office said. He is accused of using a computer at his vacation home in Lehigh Township, Pa., to download and share images and videos of children involved in sex acts.

The man who accused him of sexual abuse in 2003 said he was unaware of the Vatican’s ruling on Gugliotta, calling it “mind-blowing” that the decision appeared to be based on a technicality.

The accuser, who did not file a lawsuit or seek money from the archdiocese, questioned how the church could allow a potential threat into its parishes, particularly so soon after the clergy sexual abuse crisis exploded into national view two years earlier, in 2002.

Greg Gianforcaro, a lawyer who facilitated the accuser’s testimony before a board of church investigators in 2003, put the onus on the archdiocese. Even if Archbishop John J. Myers could not bar Gugliotta from serving as a priest under canon law, Gianforcaro argued, Myers could have at least placed him in a position away from children.

“When does common sense take over, and what about the concern for children?” Gianforcaro asked. “That’s crazy.”

Myers’ spokesman, Jim Goodness, said the archdiocese forwarded the case to Rome after it had “looked into the matter seriously.”

“Since the allegations dealt with a time frame before he was a priest, there was nothing canonically the church could do,” Goodness said, adding that he was unaware of any additional abuse claims against Gugliotta. “All I can say is the direction that was given to us by Rome is that no penal action could be taken.”

Such decisions are made by the Vatican’s Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, then headed by Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, who would become Pope Benedict XVI in 2005.

The Rev. James Connell, a canon lawyer in the Archdiocese of Milwaukee and a prominent advocate for victims of clergy sexual abuse, said the Vatican appeared to act appropriately under canon law in determining Gugliotta could not be punished for alleged wrongdoing that occurred before he was an ordained priest.

At the same time, Connell said, Vatican officials should consider amending church laws to eliminate what he characterized as a loophole that could allow potential abusers to remain in the priesthood.

“That’s worth looking at,” he said.

Connell was more forceful in suggesting Myers could have taken action to restrict Gugliotta’s ministry. Under canon law, he said, bishops have a free hand to assign priests where they see fit.

“The bishop of the diocese has a responsibility to be watching out for the care of all the people,” Connell said. “If he knows technically nothing can be done, morally something should be done, so he is not in a spot where someone could be hurt.”

One of Gugliotta’s former pastors — the Rev. John Paladino of St. Bartholomew the Apostle Parish in Scotch Plains, where Gugliotta worked with the youth group for eight years — stopped short of criticizing the archdiocese, but he said he believed he should have been told about the man’s past.

“I had no idea,” Paladino said. “As a pastor, I would want to know something like that.”

Critics of the archbishop say his handling of Gugliotta represents another misstep for Myers, who has previously been criticized for the manner in which he has managed priests accused of sexual abuse. Myers, whose retirement has been accepted by Pope Francis, is due to be replaced by Cardinal Joseph W. Tobin of Indianapolis in January.

“To me, it’s unconscionable that they allowed him to remain a priest without restrictions,” said Mark Crawford, the New Jersey director of the Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests, an advocacy and support group. “And then to allow him to be a youth minister? How reckless was that?”

Gugliotta, a nationally ranked poker player who has regularly competed in tournaments around the country, was arrested at a Toms River home Oct. 21. He was extradited to Pennsylvania last month.

The priest’s criminal defense lawyer, James Swetz, did not return a call seeking comment.

Ordained in 1996, Gugliotta has worked at St. Rose of Lima parish in Short Hills, St. Elizabeth of Hungary Church in Wyckoff, St. Joseph’s Church in West Orange, St. Bartholomew in Scotch Plains and Immaculate Conception Church in Mahwah, where he served as pastor for little more than a year before requesting a transfer in the summer of 2016.

Goodness said the request was not in response to controversy of any kind.

“He expressed that he no longer felt he wanted to be a pastor, but he still wanted to remain in ministry,” the spokesman said.

The priest had been at his latest assignment, Holy Spirit Church in Union Township, for about a week when he was charged in the child pornography case.

Gugliotta was never charged in connection with the abuse allegations that date to the mid-1980s. The accuser, whose name is being withheld by NJ Advance Media because he is an alleged victim of sexual assault, said he reported it to the Essex County Prosecutor’s Office in March of 2003, the same month he first reached out to the archdiocese.

The man, now a 46-year-old married father of two in Union County, said he was told the case could not be prosecuted because it was beyond the statute of limitations.

In a detailed letter given to the Archdiocesan Review Board — a panel that investigates sex abuse claims — and in testimony before the board in October 2003, the man said Gugliotta was a close family friend who lived near him in Newark and and who served as his troop leader in the Boy Scouts.

Beginning in 1986, he said, Gugliotta repeatedly fondled him against his will at Scout events, at his home and on family vacations. He said Gugliotta also once spied on him through his bedroom window as he masturbated.

On another occasion, the man said, Gugliotta hid in his room quietly, apparently hoping to catch him masturbating.

The accuser said Gugliotta eventually confessed to him that he was gay and that he loved him. When the man tried to avoid contact, Gugliotta continued to stalk him into his late teens, he said, at one point showing up unannounced at his college in Pennsylvania.

The man said he felt compelled to come forward in 2003 because he realized he was keeping a secret for the wrong reason and because he wanted to protect others.

“I was not asking for or looking for any reward from the archdiocese,” he said. “I just wanted solely to keep him out of a position of power where he could abuse others.”

He said he was speaking up again now because the archdiocese, despite the child pornography charges, had remained silent about the previous abuse claims until questioned by NJ Advance Media.

Crawford, of the Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests, echoed that criticism.

“They have said, in their words, they have a responsibility to be open and honest and transparent with the faithful and to put kids before the institution,” he said. “Clearly they failed at all levels here.”

Complete Article HERE!

Numerous cases have not made it that far. A 2016

Numerous cases have not made it that far. A 2016