— Why weren’t newly accused priests on Bay Area bishops’ disclosure lists?

By John Woolfolk

When Bay Area bishops a few years ago released lists of their clergy found credibly accused of sexually abusing children, they called it a commitment to confronting past failings, a move toward accountability for a colossal scandal that has scarred the Catholic Church for decades.

But the Rev. Elwood Geary’s name wasn’t on any list. Neither was the Rev. Robert Gemmet’s.

The pair of now-deceased priests, who ministered in the South Bay a half-century ago, are now accused of horrific acts in separate lawsuits made possible under a state law that opened a three-year window for abuse claims long after the statute of limitations for such crimes expired. Geary and Gemmet are just two of at least 14 clergy in Northern California – 10 in the Bay Area – who this past week were linked for the first time to the church abuse scandal.

Why they weren’t named before, abuse victims and their advocates say, stems from a shell game church leaders have played with disgraced priests. Dioceses in San Jose, Oakland and Santa Rosa — which Friday announced plans to file for bankruptcy over abuse claims — have identified their own abusive clergy. But their lists may omit offenders from back when those parishes were under the Archdiocese of San Francisco.

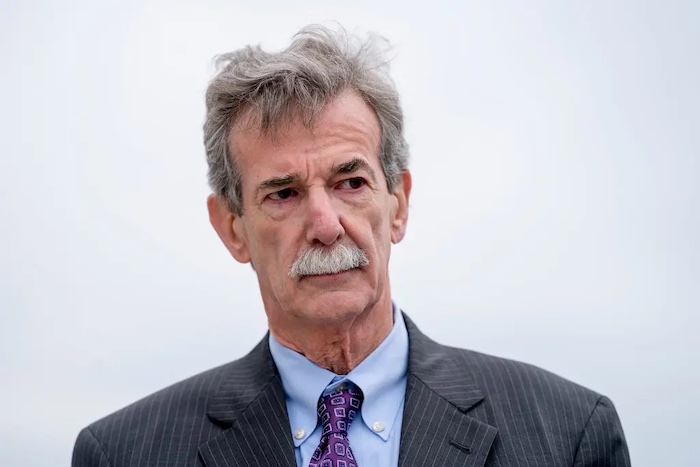

And San Francisco still hasn’t released its own list of tarnished priests. Instead, the archdiocese there, headed by the controversial Archbishop Salvatore Cordileone, lists only clergy in “good standing.”

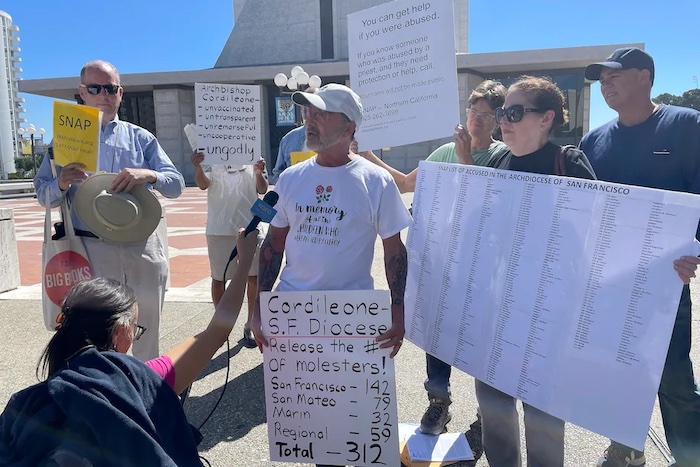

“The purpose of these lists is in part to be as transparent as possible in outreach to survivors of those priests,” said Dan McNevin, who received a settlement for abuse by a Fremont priest when he was an altar boy and now is a leader of SNAP, the Survivor Network of those Abused by Priests. “In all of this, there is a deeply disappointing lack of empathy toward survivors and a horrendous lack of accountability.”

The San Francisco Archdiocese, which currently oversees parishes in San Francisco, Marin and San Mateo counties, had said when other Bay Area bishops released their accused clergy lists that it hadn’t made a decision about doing so. But it ultimately decided to do the opposite, creating a list of current priests and deacons “who have faculties to minister here in the Archdiocese.”

“Those with questions about a priest or deacon can refer to this list,” the Archdiocese said in a statement. “The Archdiocese addresses allegations related to lawsuits through appropriate legal channels.”

It added that “any priest under investigation is prohibited from exercising public ministry in accordance with canon law” as well as policies of the Archdiocese and United States Conference of Catholic Bishops.

SNAP in September called out Archbishop Cordileone for not releasing a list of credibly accused priests in the Archdiocese, which most U.S. Catholic dioceses and institutions have done, it said. SNAP said its research identified 312 accused priests with ties to the Archdiocese, 229 of whom ministered within its current bounds, and that they believe there are others still unknown.

San Francisco’s and San Jose’s opposite approaches partly explain why Geary and Gemmet had yet to be exposed. The two were linked to South Bay churches that were under the Archdiocese of San Francisco years before the Diocese of San Jose was established in 1981.

Church officials say that timing is why the pair weren’t among San Jose’s updated 2018 list of more than 80 clergy found credibly accused of sexually abusing children.

Cynthia Shaw, spokeswoman for the Diocese of San Jose, said Geary was the founding pastor of Queen of Apostles Parish in San Jose from 1960-1979, and Gemmet ministered at St. Christopher in San Jose and St. Mary in Gilroy in the 1960s and 1970s.

Because both priests “stayed with the Archdiocese when the Diocese of San Jose was formed, the Diocese of San Jose has no personnel files for those men,” Shaw said.

Shaw said that the Diocese of San Jose “stands in solidarity” with abuse victims, offering support to them and their families. It hopes those who have come forward “can begin a process of healing.”

“Every accusation of sexual abuse is significant,” Shaw said, “and one instance of abuse is one too many.”

The Diocese of San Jose said it lists as credible allegations those that are confirmed by the clerics, their religious order or diocese or civil authorities. It also lists those deemed credible by its Independent Review Board and Sensitive Incident Team based on “pertinent and affirming details that would support an allegation against a diocesan clergy within plausible and reasonable means.” The diocese said it “will apply the same methodology to new cases upon their determination.”

The Catholic Church in the U.S. has made significant progress confronting the priest sex abuse scandal that surfaced through lawsuits, police investigations and news reports from the 1980s to early 2000s, adopting a zero-tolerance policy toward abusers known as the Dallas Charter two decades ago.

But it has been dogged for years by criticism from abuse victims that it hasn’t been fully forthcoming. Victim advocates said they were already aware of eleven of the 14 priests named in recent lawsuits, even though the church had not acknowledged them.

McNevin said the San Jose diocese is “hairsplitting when it leaves out names because of an excuse like ‘it was San Francisco then.’”

“This is a classic shuffle,” McNevin said.

A public records database indicates Geary died at age 63 in 1981 in Alameda. In one of the lawsuits, filed in December 2020, a 65-year-old man alleges Geary sexually assaulted him in 1968 when he was 11 years old and a parishioner at Our Lady Queen of Apostles Church in San Jose. The suit accused Geary of “repeatedly touching and fondling” the boy’s “genitals and forcibly performing oral sex on the child.”

According to the San Mateo Times, Gemmet was ordained in 1964 and appointed to St. Timothy Catholic Church in San Mateo. While in the seminary in Menlo Park, he worked with children at day camps in San Francisco and Redwood City and before that taught catechism to kids at St. Simon parish in Los Altos. A public records database indicated he died at age 46 in 1985.

A March 2020 lawsuit brought by another 65-year-old alleges Gemmet began “grooming” him for sexual abuse when he was a 10-year-old altar boy in 1967 at St. Christopher, leading him to believe that the “training process necessarily involved being repeatedly inappropriately sexually touched and violated.” The lawsuit alleged Gemmet threatened that “God would kill” the boy and that he “would have to watch his parents and siblings die, if he told anyone about Gemmet’s inappropriate sexual touching.”

The Diocese of Oakland, established in 1962 and including parishes in Alameda and Contra Costa counties, said it needs time to research allegations against the priests and religious sister newly linked to abuse claims within its bounds. They include John Francis Scanlon in Oakland, Domingos S. Jacques in San Pablo, Benedict Reams in Moraga and Sister M. Rosella McConnell in Berkeley. They were not among the more than 60 clergy the diocese identified as credibly accused in February 2019.

California’s AB 218 law opened a three-year window from 2020 to 2022 during which adults who say they were abused long ago as children are allowed to sue. Attorneys had predicted it would generate thousands of lawsuits against institutions including the Boy Scouts and Catholic Church.

Separately, the California Attorney General has been investigating the handling of priest abuse by the state’s Catholic dioceses, similar to a Pennsylvania attorney general probe that led to devastating 2018 grand jury findings of widespread abuse and coverups. What that may reveal is still unclear.

But Jennifer Stein, a lawyer with Jeff Anderson and Associates, a law firm handling many AB 218 cases, said the Archdiocese of San Francisco’s decision to list only priests in good standing “seems to be an intentional effort to hide knowledge of offenders.”

San Francisco’s Cordileone said in a 2018 letter to parishioners that he had hired outside consultants to review personnel files of some 4,000 clergy dating to 1950, exploring allegations received and how they were handled. He said that would take time but he would report results to the Archdiocese. So far, no report has been forthcoming.

“While I find encouragement in the progress our own church has made,” Cordileone wrote then, “there is still more to be done.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!