By Jane Musgrave

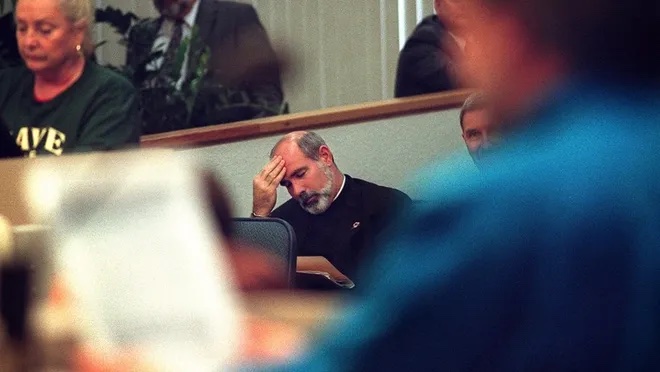

Leo Armbrust was never your typical Catholic priest.

Serving as chaplain to the Miami Dolphins, University of Miami Hurricanes and even briefly for the Dallas Cowboys, on weekends he was as likely to be seen pacing the sidelines shouting at trash-talking linemen as he was preaching the word of God to devout followers at Our Lady Queen of Apostles in Royal Palm Beach.

Known for his quick wit and a penchant for off-color jokes, Armbrust rubbed shoulders with famous athletes, business tycoons and community leaders. His well-placed connections helped him when he set off on a multi-million-dollar fund-raising odyssey to establish a Father Flanagan-style village for troubled and neglected teens.

However, 15 years after he founded Vita Nova, a less ambitious, but well-respected agency that provides housing and other assistance to hundreds of young adults no longer eligible for foster care, Armbrust is being accused of all manner of wrongdoing.

In a lawsuit filed this month in Palm Beach County Circuit Court, a former Vita Nova board member claims Armbrust, who left the priesthood in 2009, used agency accounts as his personal piggybank to fund a lavish lifestyle. In her lawsuit, Barbara McMillin accuses Armbrust, 63, of spending his days at the office trolling the Internet for sexual partners.

Further, she says, he harassed employees with crude behavior, obscene photos and anti-Semitic jokes. In at least one case, she says in her lawsuit, the agency was forced to pay a worker $200,000 to settle a sexual harassment complaint.

Her claims are salacious, provoking strong denials from agency officials and Armbrust supporters. However, the Wellington woman didn’t merely lay out her claims and leave it at that.

As part of her lawsuit, she attached confidential reports and internal memos that appear to shore up at least some of her allegations. They reveal Armbrust’s relationship with a hip-hop musician as well as statements from top staff that he was undermining Vita Nova’s work. Further, she said, she plans to send the information to law enforcement officials in hopes they will investigate.

‘Obviously, not happy’

Attorney Jack Scarola, who is being sued along with Armbrust, Vita Nova and several others, scoffed at McMillin’s attack. He said McMillin is simply trying to get back at him and Armbrust for filing a lawsuit against her and other board members for attempting to boot the former priest out of the agency he founded. While the other board members in February agreed to settle the lawsuit, award Armbrust an undisclosed amount in back pay and give him his job back, McMillin refused. So, he said, the litigation against her will continue.

“She obviously is not happy about that circumstance and has responded in what appears to be a very irrational fashion by suing everyone in sight,” Scarola said.

Attorney Gerald Richman, who filed a different lawsuit against McMillin and other board members on Armbrust’s behalf, voiced similar views. “Barbara McMillin has been extremely antagonistic toward Leo,” he said. “It’s almost like a vendetta.”

McMillin, a former CEO of Kids Sanctuary who has worked for children’s service agencies for decades, said the lawsuits Richman and Scarola filed prompted her to do some serious soul-searching about what she witnessed during her five years on Vita Nova’s board.

While she signed onto the settlement of the lawsuit Richman filed, she became suspicious when she said her own attorney wouldn’t reveal the full terms of the agreement that was hashed out with Armbrust to resolve the suit Scarola filed. She said she was appalled by the idea of giving Armbrust $100,000 to $200,000 in back pay and allowing him to return to his job as agency fund-raiser when he had proved so inept at raising much-needed cash.

“They can call me a mean old lady or whatever they want to do,” the 67-year-old said. “I just wouldn’t have felt I had done what was necessary for the kids if I hadn’t thrown this out there.”

And throw out she did.

As part of the lawsuit, she released an investigation the law firm Akerman Senterfitt did in 2012 in response to a grievance former employee Terry Sullivan filed against Armbrust.

In interviews with Akerman attorneys, Sullivan recounted the unprovoked tongue-lashings she received from Armbrust. He forced her to mend his clothes, wrap Christmas presents and go with him to pick out presents during the work day. On at least one occasion, she saw pornographic images on his computer, she told investigators.

When he began a relationship with hip-hop artist and rapper Jeancarlos Correa, who uses the stage name Remynd, Armbrust told her to prepare packages at agency expense to promote the struggling musician’s career, she said in the report.

In one instance, he asked her to order T shirts to promote Remynd’s album, “Sex and Computers.” Featuring a blow up doll with the word “Censored” stamped between its legs, the album cover image was so offensive to the printer that the agency used that it refused the order. Sullivan also told lawyers Armbrust once called her into the office to look at a sexually laced music video of Remynd, featuring the musician trying to bed a Sarah Palin look-alike.

“Ms. Sullivan said that the video did not make her uncomfortable. She stated that she ‘is not a prude,’” Ackerman lawyers wrote in their report. “However, she felt the video should not be shared in the office.”

Top brass at the agency agreed. Vita Nova CEO Jeff DeMario told lawyers that when he learned Armbrust was circulating the image from “Sex and Computers” among staff and officials from other nonprofits, he told him to stop. He also told Armbrust to stop asking Sullivan to do sewing for him.

DeMario said there were other lapses as well. He said Armbrust sometimes dressed inappropriately, such as wearing a T shirt with a photo of one of the cops from the 1970s TV show “Chips”and the words “Spread ‘em” on it. He said he had heard Armbrust make “inappropriate” jokes about black and Jewish people.

The real problem, DeMario said, was that there was little he or Irvine Nugent, another former priest who was then president of Vita Nova, could do to rein in Armbrust. While both were technically his bosses, as the founder, he had the upper hand.

“If this was anyone else, they would have been terminated,” DeMario told the lawyers. “We have an agency that is predicated on virtues and we are not practicing them in house. What kind of agency are we?”

Scarola said he hadn’t read the report that McMillin attached to the lawsuit. He said he advised Armbrust not to comment for this story. But he said the depiction of Armbrust as a bigot or a sexist is simply wrong.

“There is not an anti-Semitic bone in Leo Armbrust’s body — not the slightest hint of prejudice about anything,” Scarola said. As to those who might have found Armbrust’s jokes offensive, he said: “That’s more a reflection of their over-sensitivity rather than any impropriety on the part of Leo Armbrust.”

Armbrust’s natural exuberance and occasionally flamboyant behavior are part of his charm and the reason he is a successful fund-raiser, Scarola said. “He has excellent community connections with high-profile people,” he said. “He has established these connections with the force of his personality.”

However, there are questions about Armbrust’s fund-raising ability. Before Vita Nova board members agreed to settle the lawsuit Richman filed on Armbrust’s behalf, their attorney described Armbrust’s fund-raising as “abysmal.”

“As the director of development for (Vita Nova Foundation), Armbrust has performed poorly and has failed to bring in sufficient donations that would cover his high salary, his benefits and his assistant,” attorney Roy Fitzgerald wrote. “Since at least 2006, Armbrust has failed to meet the fund-raising budget, although the fund-raising budget was significantly lower than what should be expected.”

According to Fitzgerald’s short-lived counterclaim to Richman’s lawsuit, Armbrust earned $150,000 annually, plus benefits. An assistant made $60,000-a-year. According to industry standards, he should have been bringing in three or four times the $210,000 the agency was spending on his office, roughly $630,000 to $840,000 annually. Records show its investment portfolio declined from $15.7 million in 2006 to $6.2 million in 2013. The agency also gets government grants.

“Armbrust sets his own schedule and does not invest the necessary time and energy into fund-raising or into the organization to understand the programs the organization offers,” Fitzgerald continued. “As such, Armbrust has failed at getting the necessary fund-raising and could do more.”

Since that lawsuit was settled, Vita Nova board members and executives have changed their tunes. They dispute the allegations McMillin is making in her recently filed suit.

“Much of what Ms. McMillin alleges in her complaint is substantially inaccurate,” DeMario said in a statement. “As an organization, we are saddened that Ms. McMillin has taken a path that may harm the very organization that she was once affiliated with and may impact the hundreds of young adults we serve.”

McMillin said that isn’t her intention. She said the organization is a good one and praised DeMario as doing good work against enormous odds.

“I truly hope and I pray that people will support the organization,” she said. “They are doing a fabulous job for kids who need their support. But it just isn’t right to allow Leo to go on and give that man money that should go to the kids.”

Scarola said McMillin may pay a heavy price for her actions. By releasing confidential information she may have put Vita Nova at risk. “Clearly, she had a fiduciary responsibility as an officer of the corporation to preserve the confidence of the corporation,” he said.

McMillin said she’s not worried. “Protecting Leo is not part of my fiduciary responsibility,” she said.

Further, she said, she’s not done. After Easter, she said she plans to ask the Palm Beach County state attorney, Florida attorney general and the IRS to look at the records she has collected. Not all of them are in the lawsuit, she said. She said she has credit card receipts that prove Armbrust was using agency money as his own.

“I’m not trying to destroy the foundation. I am trying to save the foundation,” she said. “He has been looting it for years.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!