When a group of local Catholics decided to expand their advocacy work outside a Whitefish Bay living room, they had to come up with a name for their new organization.

They settled on “Awake Milwaukee.”

As Catholics who wanted to push for change on the issue of sexual abuse from within the church, the name represented their own views as well as what they hoped to do for others.

“We felt like we were finally awake. We were finally paying attention to something that had been there all along,” said executive director Sara Larson. “It’s also what we’re aiming to do for our broader community: to help people wake up to this reality.”

The group’s ethos is that while the Archdiocese of Milwaukee has come a long way in addressing clergy abuse, more can be done to support survivors and increase transparency. The group has also recently released a list of recommended changes.

Awake is unique among most anti-clergy sexual abuse groups because its leaders are practicing Catholics who want to remain in the church and see it improve.

“Real change and structural change can only come from within, when the laity really is speaking and saying we’re not comfortable with where this is at,” said Patty Ingrilli, a member of Awake’s board of directors.

An archdiocese spokeswoman said the church has put stringent policies in place to prevent abuse, worked with survivors and given anti-child abuse training to 100,000 people.

“No organization in the U.S. has done more than the Catholic Church when it comes to addressing sexual abuse, and incorporating prevention measures throughout the organization,” said communication director Sandra Peterson.

‘It’s about listening first’

A lifelong Catholic with a theology degree, Larson was working at a local parish in 2018 when two pieces of news hit her like a “punch in the gut” and caused her to pay attention to the abuse crisis. The cardinal Theodore McCarrick was removed from ministry over allegations of child sex abuse, and the sprawling Pennsylvania grand jury report was released, detailing widespread abuse and cover-ups.

Previously, Larson believed a narrative she thinks is common among Catholics: Sexual abuse in the church “happened a long time ago, and when we found out about it, we fixed it, and now it’s time for us to move on.”

Within a year, Larson had dived into research on the crisis, hosted other local Catholics in her home for discussions on the issue and launched Awake Milwaukee.

The group’s first action was an open letter to survivors, apologizing for the abuse they experienced and for the “many ways your abuse was ignored, minimized, and covered up.” Dozens of local Catholics, including priests and deacons, signed on.

Most of the group’s founders weren’t survivors of abuse or close family or friends of survivors. But they were people of faith who cared.

“We were people who maybe had been part of the problem by not caring enough about this, and not learning and not taking action earlier,” Larson said.

Ingrilli, a Brookfield Catholic who’d served as chair of her parish council, got involved because it was important to raise her three sons in the church, she said.

“I needed the Catholic Church to be a safer place than what I felt it was,” she said.

Awake has four areas of focus: education, prayer, advocacy and survivor support.

Educating “Catholics in the pews” about “the full reality of sexual abuse” in the church is key, Larson said. Awake runs a blog and hosts regular panel discussions with survivors and experts.

It’s been painful that some Catholics don’t support Awake’s mission, she said.

“We really think that a lack of understanding is a huge part of the problem,” she said.

Awake also runs support groups for survivors of clergy abuse. The virtual groups have drawn survivors from across the U.S. and Canada, Larson said. Not all experienced abuse within the Milwaukee archdiocese.

Most of the survivors have remained in the church and were looking for a place to be honest about the crisis while remaining “rooted in faith and hope,” Larson said.

“People want to be heard, and they want to be believed. That is the foundation of everything we do,” Larson said. “It’s about listening first.”

Group compiled list of recommendations

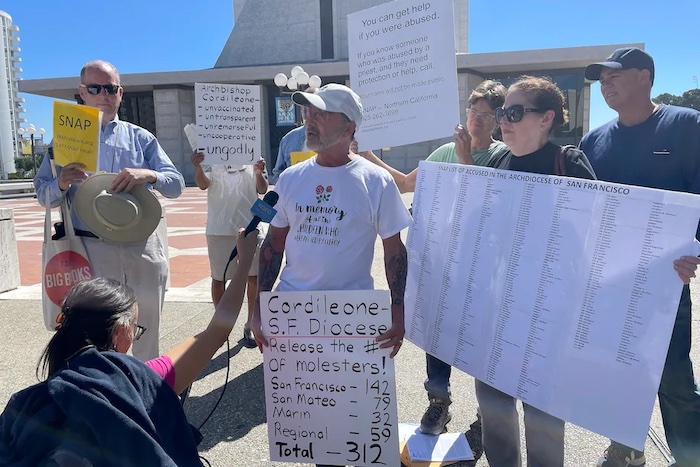

Awake recently released a list of recommended policy changes for the Archdiocese of Milwaukee.

Among the recommendations: publish an online list of all priests credibly accused of abuse in the archdiocese, including visiting priests and those from religious orders – the current list only includes diocesan priests; publish twice-annual reports detailing the work of two oversight boards; and acknowledge the sexual abuse of adults, not only children, in Archdiocesan documents.

Each recommendation includes reasoning for why Awake leaders believe it should be implemented, as well as examples of dioceses that have implemented it.

“We really wanted to focus on things that, from what we understand, are very possible,” Larson said.

While some changes may seem minor, they can have a big impact on survivors, Larson said. Take the suggestion to list all credibly accused priests online.

She says that an average parishioner likely would make little distinction between a diocesan priest and, for example, a priest who was ordained in the Archdiocese of Chicago but was working at a church in Milwaukee.

A survivor “could go looking and say, ‘my abuser is not on this list,’” Larson said.

And while so-called extern and religious-order priests aren’t directly accountable to the Milwaukee archbishop, “it’s just a really good way to increase transparency about the full scope of abuse that happened in our archdiocese,” Larson said.

The archdiocese says it does not list extern and religious-order priests because it has no way of knowing key details about abuse allegations against such priests and how they were investigated. “There is also no certainty that the Archdiocese would be informed of allegations against every priest who worked at some point in the Archdiocese,” the statement said.

Another of Awake’s recommendations is to be more public about the work of two lay-led oversight boards, which provide advice to the archdiocese on its clergy abuse policies and whether people are fit to serve in ministry.

In response to a reporter’s question about the recommendation, the archdiocese spokeswoman said the Community Advisory Board includes survivors of abuse, victim advocates, professional psychologists and therapists, and members of law enforcement.

The board meets regularly and “serves as an instrument of education and vigilance and as a pathway of archdiocesan accountability to the larger community,” Peterson said.

Especially important to Larson is the recommendation to expand protections for child victims to adults. It’s not just children who are vulnerable to power differentials, she said: women in religious orders, adult seminarians and lay leaders also suffer sexual abuse.

“I’ve come to believe that the abuse of adults in the church is that it’s happening on a really broad scale today and still being tremendously mishandled by the church,” Larson said.

Awake Milwaukee has not received a response after sharing the recommendations with archdiocese officials.

“My hope is at least that they can see that the recommendations have merit and that even if they don’t directly respond to us, that it just makes them think,” Ingrilli said.

Ingrilli led a campaign last year to ask the archdiocese to ban liturgical music from David Haas, a widely known contemporary composer who was accused of sexual misconduct by dozens of women. Officials didn’t reply. The decision whether to play Haas’ songs falls to individual parishes.

In response to a reporter’s questions about the lack of response to Awake’s leaders, Jerry Topczewski, chief of staff for the archdiocese, issued a statement:

“We are always open to input from professionals regarding the Church’s considerable and ongoing efforts assisting those who were victims of clergy sexual abuse of minors, while also remaining vigilant in our abuse prevention and safe environment efforts.”

Catholicism ‘part of the fabric of my life’

Even as they find little traction with archdiocesan officials, Awake’s leaders remain committed to their cause as well as their faith.

It hasn’t been easy.

“I had no idea, when I said yes to this, how much it would break my heart,” Larson said. “The depth of the pain and the depth of the wounds that are still present in the church is just not something that I understood.”

For Ingrilli, the group’s work has been personal. She found her great-uncle’s name on the Green Bay Diocese’s list of credibly accused priests. Her priest working at her hometown parish in Kiel, a Salvatorian from the Buffalo diocese, was also accused of abuse but wasn’t removed from ministry until decades later.

The discoveries galvanized her to make a difference within the church. She didn’t consider leaving it.

“That is part of the fabric of my life. That is very much who I am. I can’t imagine not having it,” Ingrilli said.

Ultimately, Ingrilli hopes Awake’s work prompts enough change that people who have left the church feel comfortable enough to return.

It’s her way of evangelizing, she said.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!