By Shawn Boburg Robert O’Harrow Jr.

It was billed as a holy journey, a pilgrimage with West Virginia Bishop Michael J. Bransfield to “pray, sing and worship” at the National Shrine in Washington. Catholics from remote areas of one of the nation’s poorest states paid up to $190 for hotel rooms and overnight bus rides to the nation’s capital.

Unknown to the worshipers, Bransfield traveled another way. He hired a private jet and, after a 33-minute flight, took a limousine from the airport. The church picked up his $6,769 travel bill.

That trip in September 2017 was emblematic of the secret history of Bransfield’s lavish travel. He spent millions of dollars from his diocese on trips in the United States and abroad, records show, while many of his parishioners struggled to find work, feed their families and educate their children.

Pope Francis has said bishops should live modestly. During his 13 years as the leader of the Diocese of Wheeling-Charleston, Bransfield took nearly 150 trips on private jets and some 200 limousine rides, a Washington Post investigation found. He stayed at exclusive hotels in Washington, Rome, Paris, London and the Caribbean.

Last year, Bransfield stayed a week in the penthouse of a legendary Palm Beach, Fla., hotel, at a cost of $9,336. He hired a chauffeur to drive him around Washington for a day at a cost of $1,383. And he spent $12,386 for a jet to fly him from the Jersey Shore to a meeting with the pope’s ambassador in the nation’s capital.

Pope Francis has said bishops should live modestly. During his 13 years as the leader of the Diocese of Wheeling-Charleston, Bransfield took nearly 150 trips on private jets and some 200 limousine rides, a Washington Post investigation found. He stayed at exclusive hotels in Washington, Rome, Paris, London and the Caribbean.

Last year, Bransfield stayed a week in the penthouse of a legendary Palm Beach, Fla., hotel, at a cost of $9,336. He hired a chauffeur to drive him around Washington for a day at a cost of $1,383. And he spent $12,386 for a jet to fly him from the Jersey Shore to a meeting with the pope’s ambassador in the nation’s capital.

Bransfield was barred from public ministry in July after an internal church investigation found he had engaged in financial abuses and sexually harassed young priests, allegations Bransfield has denied. The Post previously obtained the investigative report and revealed its major findings, including that he spent $2.4 million of church funds on travel and gave $350,000 in cash gifts to other clerics.

To gain a deeper understanding of Bransfield’s travel expenditures, The Post reconstructed his movements in the year before he retired in September 2018. The reporting drew on receipts obtained by The Post, public flight records and the confidential findings of the church’s own investigation as well as interviews with some of Bransfield’s companions and travel company representatives.

Bransfield was outside of West Virginia for a total of almost four months, according to documents and interviews. Though most of that travel was not related to his duties in West Virginia, the diocese routinely covered Bransfield’s expenses as well as those of the young priests who accompanied him, The Post found.

“This is so much worse than we ever imagined,” Michael Iafrate, a church activist in West Virginia, said when told about The Post’s reporting. “It is profoundly, morally wrong.”

In an interview, Bransfield, 76, did not dispute the findings but defended his frequent vacations as necessary breaks from his religious responsibilities.

Bransfield said he never made travel arrangements for himself, and he blamed his aides for selecting luxury accommodations, including the penthouse in Palm Beach. “I did not arrange that room,” he said. “That was done by staff.”

He said much of his travel was related to his role as president of the Papal Foundation, a nonprofit entity that raises money from wealthy Catholics for Vatican initiatives.

“Usually it was business,” he said.

The church’s internal investigation, completed in February, found that three of Bransfield’s top aides had enabled him. After The Post reported on the probe’s findings in June, the diocese announced that the aides had resigned from their administrative positions. They have not responded to interview requests.

Bransfield could face financial consequences for his actions. Pope Francis has said the former West Virginia bishop must “make personal amends,” and in response to questions from The Post, the diocese said it may seek to recover money Bransfield spent inappropriately.

In a statement, the diocese said Bransfield’s successor, Bishop Mark Brennan, has launched an internal audit “to determine what, if any, of Bransfield’s expenses were connected to Church business.”

“If Bishop Bransfield is not cooperative, Bishop Brennan has stated he intends to exercise his unilateral authority to recover funds that we can determine were primarily used for personal benefit,” the diocese said.

Bransfield arrived in West Virginia in 2005 after a quarter-century in Washington in various posts at the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception, the largest Catholic church in North America.

Bransfield told The Post that he had grown accustomed to the comfortable lifestyle he led in those years. He had befriended celebrities and politicians, including former House speaker Newt Gingrich, who credited Bransfield and others at the National Shrine with helping convert him to Catholicism. His allies and friends included some of the most powerful clerics in the country.

In West Virginia, Bransfield took responsibility for a vast diocese in great need. Nearly 1 in 5 state residents lived in poverty, the opioid epidemic was spreading and even coal mining jobs — a mainstay of West Virginia’s hardscrabble economy — were hard to come by.

Bransfield had access to an obscure source of riches. More than a century ago, a New York heiress donated land in West Texas to the West Virginia diocese. The land turned out to be rich with oil, generating annual revenue of almost $15 million in recent years.

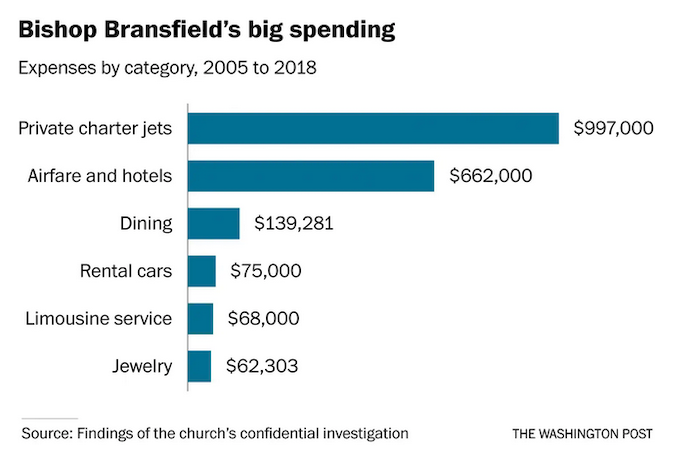

Bransfield did not call attention to that revenue publicly, but the diocese drew on it to cover his travel expenses and other personal spending, according to the confidential investigative report. During his 13 years in West Virginia, Bransfield spent $4.6 million on renovations to his church residence, almost $140,000 at restaurants, $62,000 on jewelry, and thousands on alcohol, the report shows.

By his final year, records show, Bransfield’s use of private jets and limousines had become routine — even as the diocese closed or cut funding for nearly two dozen parishes and parochial schools.

On Sept. 16, 2017, as parishioners traveled by bus for the pilgrimage to the National Shrine, Bransfield boarded an 11-seat Learjet.

When Bransfield arrived at Dulles International Airport, a hired luxury car was waiting outside a small terminal devoted to executive jets, according to receipts from the chauffeur service Limolink. The firm told The Post that its fleet is primarily made up of Mercedes-Benzes and BMWs. The ride to the National Shrine and back to the jet several hours later cost $440, receipts show.

In his last year, Bransfield flew by chartered luxury jet at least 19 times at a cost of over $142,000, according to receipts from Skyward Aviation, a charter firm that provides “concierge” service for well-heeled travelers from an airport about 30 miles from the diocesan headquarters. During his entire tenure in West Virginia, Bransfield spent almost $1 million on private jets, according to the investigative report.

“Welcome to luxury and comfort at its finest,” Skyward Aviation says on its website.

Bransfield’s use of private jets was no secret to two of the pope’s close advisers. The Vatican’s diplomatic representative in the United States, Christophe Pierre, and his predecessor Carlo Maria Viganò each rode on a jet paid for by the diocese, according to receipts and interviews.

Pierre’s July 24, 2017, flight back to Washington from a Boy Scouts event in Charleston, W.Va., cost $7,596.

Pierre and officials in his office did not respond to requests for comment about the previously unreported flight.

Viganò previously told The Post he did not know his 2013 flight — also to a Boy Scouts event — was paid for by the West Virginia diocese.

A Vatican spokesman did not respond to emails seeking comment.

Bransfield also routinely traveled in luxury overseas. During his tenure, he visited Paris, London and Geneva, often flying first-class and staying in leading hotels, and was at times accompanied by young priests, according to records and interviews.

One of those priests is the Rev. Andrew Fisher, the pastor at St. Ambrose Catholic Church in Annandale, Va., who worked with Bransfield at the National Shrine. Fisher described the trips — including at least four to Paris and London — as “a blend of vacation and work.”

“After he moved to West Virginia, I was asked to take a number of trips as his guest and was told the trips were paid for out of the bishop’s personal finances,” Fisher said in a statement. “I had no role in selecting the accommodations or making travel arrangements, and I was unaware of the costs.”

In late October 2017, Bransfield asked a cleric in his mid-20s to accompany him on a trip to Rome, according to the confidential investigative report. The priest, based in West Virginia, only reluctantly agreed. He had confided to one of the bishop’s top aides that Bransfield had once slapped his buttocks during a summer party, the report said.

The Post generally does not name the victims of alleged sexual harassment. He declined to comment.

The pair visited Castel Gandolfo, a lakeside village south of Rome, according to the investigative report. During the visit, Bransfield upset the priest by again slapping him on the buttocks, the investigative report said.

Bransfield has denied any inappropriate contact with priests or seminarians.

Several weeks after returning to West Virginia, Bransfield took another charter jet to Washington, for a meeting of the Philadelphia-based Papal Foundation. The group is run by U.S. cardinals and was founded by a close ally of Bransfield’s, then-Cardinal Theodore McCarrick, who was defrocked earlier this year for sexual abuse.

As president of the group, Bransfield helped manage more than $225 million in total assets, according to internal Papal Foundation documents. He also used private jets and limousines paid for by his diocese to visit wealthy Catholic contributors.

Bransfield arrived in the nation’s capital several days before the foundation’s December 2017 meeting. He racked up nearly $2,000 in bills at the Hay-Adams Hotel, which overlooks the White House. Bransfield dined at the Capital Grille in Chevy Chase, Md., and at Cafe Milano in Georgetown. He also spent $400 at Nieman Marcus, documents show.

In an interview with The Post, Bransfield lamented the lack of shopping opportunities in the Mountain State. “I didn’t have the opportunity in West Virginia to live the lifestyle I lived in Washington,” he said.

A favorite store in the nation’s capital was Ann Hand Collection, a boutique jeweler where he spent $61,785, according to the investigative report.

Owner Ann Hand said in an interview that Bransfield often visited the showroom and bought pins, cuff links and silk scarves for friends and colleagues. Bransfield blessed the shop when it moved to its location in Georgetown several years ago, she said.

Hand expressed surprise when told how much church money Bransfield spent on the gifts.

“That is shocking it would be that much,” Hand said. “I guess I honestly thought he was a priest who had his own money.”

On the final day of his D.C. visit, Bransfield attended the Papal Foundation meeting. The Dec. 12 gathering brought together top U.S. Catholic leaders and a handful of wealthy Catholic donors who helped steer the foundation.

Bransfield assured the donors that Pope Francis would meet with them to acknowledge their generosity during the group’s annual pilgrimage to Rome in the spring, according to minutes of the meeting.

Afterward, Bransfield stepped out of the Vatican’s embassy on Massachusetts Avenue and got into a limousine that took him to a private jet waiting to fly him back to West Virginia, according to a Limolink receipt.

Nearly two weeks later, at midnight on Christmas Eve, Bransfield was standing at the altar at the Cathedral of St. Joseph in Wheeling, W.Va. He was surrounded by red and white poinsettias. He celebrated a Mass that was broadcast on television stations across the state.

Hours later, he was gone again.

On Christmas afternoon in 2017, he flew by private jet to Philadelphia, his hometown. He hosted a holiday soiree at a catering hall not far from a Philadelphia home he owns — at a cost to the diocese of more than $5,000, according to a person familiar with the event who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss a private matter.

On Dec. 28, Bransfield and another Philadelphia priest, the Rev. Monsignor Charles P. Vance, flew on American Airlines to Palm Beach International Airport. Records show Bransfield routinely took winter vacations at the diocese’s expense — and not just to Florida but to the Cayman Islands, St. Maarten and St. Barthelemy in the Caribbean.

As a tax-exempt charity, the church is prohibited from spending on luxuries or services that unduly benefit an individual.

In Palm Beach, Bransfield and Vance stayed for a week at the Colony, a boutique hotel that hosted Presidents Bill Clinton and George H.W. and George W. Bush and once was a favorite of British royalty.

From Dec. 28, 2017, to Jan. 4, 2018, the two clerics stayed in the Presidential Penthouse, a 1,640-square-foot spread with two bedrooms as well as living and dining rooms and a private sun deck, according to a hotel executive, accounting manager Mimi Hector.

Over the years, Bransfield spent almost $50,000 of the diocese’s money at the hotel, sometimes for multiple rooms, records show.

In his Post interview, Bransfield described the hotel as “a very classy little place,” convenient to the beach and Palm Beach’s legendary shopping district. Yet he called the choice of the suite an error of judgment by his staff.

“It only happened once,” Bransfield said. “I made sure it was not repeated.”

Hector told The Post that Bransfield had previously stayed in another of the Colony’s premium suites — the Duke of Windsor Penthouse.

For the return flight from Palm Beach, Bransfield did not use his round-trip ticket on American Airlines. He never sought a refund for the return portion of the $2,854 trip, an airline representative said.

Instead, he took a private jet from Palm Beach International Airport to the airport near his residence in Wheeling.

Bransfield said he did not recall forgoing the commercial flight.

“I had nothing to do with arranging the flights,” he said. “That was staff.”

Vance, the pastor of St. Philip Neri Church in Lafayette Hill, Pa., traveled to Palm Beach with Bransfield for winter vacation four times in recent years. He told The Post that he assumed that the trips and related expenses were “gifts” from Bransfield’s diocese.

“I never felt comfortable in Palm Beach,” he said. “It was just too extravagant for me.”

Vance said he had nothing to do with the arrangements.

“I was just a guest,” said Vance, who had attended seminary with Bransfield. “As far as I knew, it was something they were doing for him. It was arranged by his staff.”

Bransfield flew south twice more last winter at church expense.

In late January, he visited Miami Beach for a week-long vacation with the same young priest who accompanied him to Rome. Bransfield’s aide, Monsignor Kevin Quirk, the judicial vicar of the West Virginia diocese, instructed the priest to accompany Bransfield because “there is no one else” willing to go, according to the investigative report. The priest reluctantly agreed, according to the investigative report.

Quirk did not respond to requests for an interview.

Bransfield also spent four days in Aruba in March. In an interview, he described the visit as “a small vacation.”

In April 2018, when Bransfield returned to Rome with Papal Foundation contributors, he took a side trip to relax. This getaway was in the seaside village of Positano, on Italy’s Amalfi Coast.

“I was working very hard,” Bransfield told The Post. “And I took two or three days off. That was strictly personal.”

Bransfield racked up a $3,333 bill staying at Le Sirenuse, regularly ranked in leisure magazines as one of Europe’s finest hotels, records show.

“I did not pick the hotel,” Bransfield said. “Someone else did.”

Bransfield declined to say who selected the hotel.

Two weeks after returning to West Virginia, Bransfield was again headed to Washington aboard a private jet. A limousine picked him up at 11:09 a.m., a receipt shows. Bransfield stopped at the Vatican diplomatic office and another church facility. While the limousine waited, he got a haircut at Salon ILO in Georgetown, according to a salon employee. The diocese covered the $80 haircut, records show.

A growing number of Bransfield’s subordinates, including some of his closest aides, were privately grumbling about his financial and sexual conduct, according to interviews and the investigative report.

Complaints about Bransfield’s financial activity were not new. Parishioners in the state had sent letters to Vatican officials six years earlier seeking an investigation of his spending, The Post previously reported. Four senior clerics in the United States and at the Vatican who received written complaints about Bransfield in previous years had also received cash gifts from the bishop.

But in the summer of 2018, the allegations took on a new significance.

Two young priests who had traveled with Bransfield overseas had gone to Baltimore Archbishop William Lori with claims that Bransfield sexually harassed them. In August, Quirk wrote an eight-page letter with allegations about financial abuses, including that Bransfield spent money excessively on travel, according to a copy obtained by The Post.

Quirk made many of the travel arrangements, according to the travel receipts.

At the time of Quirk’s Aug. 8 letter, Bransfield was on his annual vacation on the Jersey Shore, where he regularly spent up to a month with family members and friends, with the diocese footing many of the bills. He made a $276 purchase at one of his regular stops each summer: a liquor store in Somers Point, N.J. He spent $1,002 at the Flanders Hotel in Ocean City, and he rented a car for the month at a cost of $2,975.

On Aug. 25, Bransfield was summoned to the nunciature in Washington. Instead of driving down Interstate 95 — a trip that could take up to four hours — he chartered a private jet from Atlantic City. He hopped into a limousine for the trip to the nunciature, the Vatican’s diplomatic office in Washington, receipts show.

Bransfield told The Post that that was when he first learned that his job was imperiled.

“It was the worst day of my life,” Bransfield said.

He took the jet back to the Jersey Shore.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!