As a matter of urgency, the new pope must extend the gift of marriage to all priesthood candidates. Failure to do that will mean, in less than a generation, a priesthood comprised solely of social misfits and emotionally damaged refugees from reality.

By Kevin McKenna

Of all the theories advanced explaining why the Catholic priesthood attracts so many young gay men, this is the most valid: it is a direct consequence of the church’s official attitude to homosexuality and the way that this has insinuated itself into the fabric of what we might call a traditional Catholic family with its roots in Ireland.

In such an upbringing homosexuality is still treated as the sum of all sins. Catholic families long ago found a way of dealing with abortion, extramarital sex and divorce, the other three horsemen of the Catholic apocalypse, whenever they occurred close to home, but not homosexuality.

In such an upbringing homosexuality is still treated as the sum of all sins. Catholic families long ago found a way of dealing with abortion, extramarital sex and divorce, the other three horsemen of the Catholic apocalypse, whenever they occurred close to home, but not homosexuality.

The others could all be processed and interpreted as very human failings stemming from the powerful instinct of physical desire and our need for affection and love. The Christian virtues of understanding, compassion and forgiveness are built to outlast initial shock and hurt in these “acceptable” moral failings. Not so homosexuality.

For how many Catholic parents have secretly prayed that their son “does not turn out gay” or obsess about their response if the eldest boy shows no interest in football and insists on taking a shower every day and buying all his own clothes? The church’s pastoral care and guidance for its own gay community is nonexistent. Catholic gays are non-people in my church; they are “los desaparecidos” and one day many of us will be called to account for how we have treated them.

The church has nothing to say to a child reared in these circumstances and who is beginning to encounter issues with his sexual identity. And so, by a perverse irony, the Catholic priesthood becomes a viable option for him. For what better way to submerge your “problem sexuality” than by committing yourself to a life of celibacy and a lifetime of reflection on the burden that God has deemed you must bear for your redemption and his glory?

Neither of these, though, explains why a church which has become a haven for homosexual men has become so obsessive about warning the rest of us about the dangers of gay sex.

Cardinal Keith O’Brien, Britain’s most senior Catholic cleric, has been accused of “inappropriate behaviour” towards four priests, stretching back 30-odd years. Thus far he has refused to “deny” the claims, merely to “contest” them. The press office for the Catholic church in Scotland, by way of explanation, lamely insists that the cardinal does not know the identity of his accusers, nor the details of which he is being accused.

Has such behaviour occurred so many times that the cardinal simply has trouble recalling specific instances? Or might he genuinely think that what the priests describe as “inappropriate behaviour” was merely a misunderstanding arising from an encounter with an over-affectionate and tactile boss?

The sullen “no comments” and “I can’t help you” are curious, too. This is an organisation that has become the church’s de facto witchfinder-generals, ever vigilant for examples of anti-Catholicism and never missing an opportunity to portray this country as bigoted and backward.

Like the entire hierarchy of the global Catholic church, they are in complete denial about a culture of sexual dysfunction that has been operating at its core for several decades. Hardly a year passes without an example of grotesque sexual behaviour, both homosexual and heterosexual, by a priest or bishop in the church.

The damage to the church is incalculable. In response to last week’s Observer story, the historian Tom Devine, a Catholic, described it as the church’s biggest crisis since the Reformation. It means that the Scottish Catholic church has lost all authority to speak on matters of human relationships until it at least recognises the root of the problem. Quite simply, the Catholic hierarchy in Scotland is no longer fit for purpose. It hasn’t been for a long time now: its default position is denial and concealment before accusing its critics of being motivated by bigotry.

The Vatican says it will investigate the complaints of the cardinal’s accusers. I have very little faith that an inquiry conducted in another country and of indeterminate legal structure and under the authority of another old man in Rome – identity, as yet, unknown – will deliver anything resembling a just outcome.

Nothing less than a full-scale investigation into the structure and leadership of the Scottish Catholic church will suffice to begin the task of recovering its lost authority. The commission to oversee this must be headed by an overseas cardinal of impeccable character and must comprise clergy and lay people in equal measure.

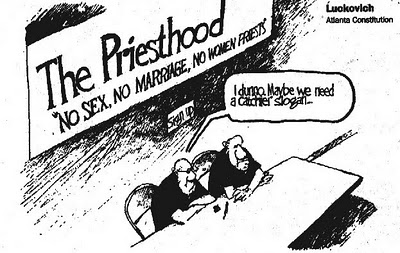

As a matter of urgency, the new pope must extend the gift of marriage to all priesthood candidates. Failure to do that will mean, in less than a generation, a priesthood comprised solely of social misfits and emotionally damaged refugees from reality. Ordinary Catholics have been incessantly grossly betrayed by the Catholic hierarchy. It is time we ignored the weekly collection plate until we receive some answers.

Complete Article HERE!