Trials, Lawsuits, and Financial Strains

By Neil Pang

With Apuron’s canonical trial underway and a slew of civil lawsuits filed in Guam, the Catholic Church confronts new crises here and at the Vatican

With the Archdiocese of Agaña facing 13 lawsuits alleging child sexual abuse – and the real potential for additional suits to follow – the Catholic Church is preparing for what could be a drawn out and highly publicized exposure of alleged abuses and cover ups, as well as court ordered payouts possibly adding up to millions of dollars.

At the center of the current tumult are two interrelated events: the allegations of child sexual abuse leveled against local archdiocesan clergymen and the passage of Bill 326-33 into Public Law 33-187 that eliminated the statute of limitations in cases involving child sexual abuse.

Years of controversy

Contention and controversy were not new to the Archdiocese of Agaña prior to the May 17 statement made by Roy Quintanilla that alleged child sexual abuse against Archbishop Anthony Apuron.

For at least six years prior to Quintanilla’s accusation, Apuron often found himself the subject of news stories that intimately connected him to instances of alleged cover-ups of priests accused of abuse.

In 2010, Apuron was criticized by leaders of the Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests (SNAP) when it came to light that local priest Rev. Raymond Cepeda had been defrocked over allegations of abuse made against him. That revelation was exacerbated when, shortly thereafter, two other priests who served under the Archdiocese were found to be no longer engaged in public ministry after their ministerial authority had been permanently revoked due to allegations of sexual abuse.

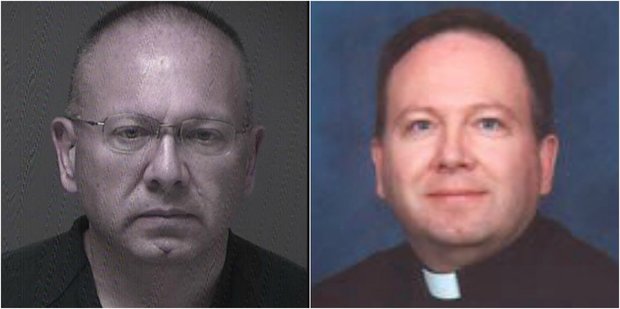

According to Post files, Rev. Randolph “Randy” Nowak and Rev. Andrew “Andy” Mannetta were stripped of their ministerial authorities, in 2004 and 2002 respectively, over allegations of abuse that occurred off-island against individuals who were minors at the time.

SNAP had requested that Apuron follow in the steps of other dioceses and post a list of all priests accused of sexual abuse that had or currently did serve under the Archdiocese of Agaña. Apuron never complied with SNAP’s request.

In 2014, Apuron was again targeted by SNAP. The group, asserted that Apuron engaged in “dangerous” behavior when he knowingly allowed a clergyman, Rev. John Wadeson, accused of sexual abuse in Los Angeles, to minister in the Archdiocese of Agaña. Apuron denied prior knowledge of the accusations against Wadeson. Following the publication of molestation allegations by SNAP, Post files state that Wadeson was removed from the Archdiocese of Agana.

Apuron was also accused of mismanagement of multi-million dollar church assets when, in 2011, he filed a deed restriction on the Redemptoris Mater Seminary that certain legal opinions asserted essentially transferred control of the Yona property from the Archdiocese of Agaña to a nonprofit organization outside the purview of the church.

Then, in a seeming crescendo, Apuron himself was named in a series of child sexual abuse accusations starting with Quintanilla in May of 2016. Quintanilla, a former altar boy from the Agat parish where Apuron ministered in the 1970s, was followed by Doris Concepcion – the mother of Joseph A. Quinata, who admitted to her shortly before his death in 2005 of being sexually abused by Apuron in the late 1970s.

The two were joined by Walter Denton and Roland Sondia in June when they made similar accusations of abuse against Apuron.

Subsequent accusations have been made against other priests who served on Guam at various times in the past decades, including Rev. Louis Brouillard, Rev. Antonio Cruz (deceased), and Rev. David Anderson.

Save for a few videos and selfies published online from Rome in early summer and a prepared statement welcoming the appointment of his successor last month, Apuron has been unusually silent. All that is known is that he remains at the Vatican in Rome, where, according to Guam’s new archbishop, Michael Jude Byrnes, a canonical trial is now underway

According to clergy child sex abuse advocate Patrick J. Wall, Apuron could be the first Archbishop to survive a canonical trial.

“The new Archbishop [Byrnes] reported that the canonical trial of [former] Archbishop Apuron is underway,” Wall said in an email. “This is new ground in the modern world as no Bishop I am aware of who sexually abused children has ever finished a canonical trial. Archbishop Wesolowski died prior to the completion of his trial in Rome.”

Wesolowski was the former Holy See envoy to the Dominican Republic who was accused in 2013 of sexually abusing teenage boys and defrocked in 2014, according to the International Business Times. At the time, Wesolowski was the highest-ranking Vatican official ever to be investigated for sex abuse, and was the first top papal representative to receive a defrocking sentence.

Though Wesolowski was successfully laicized, or had his clerical status revoked, he died before standing trial for accusations of possessing child pornography, for which he faced a possible prison term.

Canonical trial

While survivors of alleged abuse continue to come forward in suits filed against the Archdiocese of Agaña and its clergymen, questions abound as to the current status of Apuron’s canonical trial in Rome.

Wall, who has extensive experience in the field of Catholic clergy abuse and is currently an advocate at Jeff Anderson and Associates, explained that the trial itself will proceed as follows:

First, a complaint is filed by the Promoter of Justice, what the church calls the prosecutor, at the Congregation of the Doctrine of the Faith, the Vatican office responsible for upholding the integrity of the Catholic Church.

The next step is where Wall says the trial likely is now. According to his explanation, the Vatican court will receive an answer to the complaint written by the Respondant’s canonical advocate.

Referring to statements made by Byrnes on Nov. 28 that the “initial phase” of Apuron’s trial had started, Wall said Byrnes had indicated that Apuron had received the written charge from the Promoter of Justice and that the next stage was discovery.

During the discovery phase, Wall explained that documents, depositions, and all relevant evidence would be exchanged.

Trial and determination by a panel of three Clerical Judges would follow with penalties up to and including dismissal from the clerical state. Additional “lower penalties” are also imposed at this time and, if applicable, the Pope would then need to assign Apuron to a monastery or some other appropriate location, according to Wall.

While it is unclear exactly what charges Apuron received from the Promoter of Justice, it is pertinent to note that, according to “The Norms of the motu proprio ‘Sacramentorum Sanctitatis Tutela’,” the 2001 letter by Pope John Paul II that amended the Code of Canon Law to include sexual abuse of a minor under 18 by a cleric among the new list of canonical crimes or “delicts” reserved to the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, canon law stipulates a 10 year statute of limitations on cases involving child sexual abuse that begins from the year the victim turns 18.

Regardless of what charges Apuron is presented with, the Code of Canon Law contains additional provisions under which Apuron could potentially be charged with other “grave delicts” and removed.

However, as indicated by Wall, the procedures outlined for canonical trials move slowly, and that any determination made following the discovery phase could take months to articulate. During that time, the secular courts will also have to move forward with their own proceedings, with or without Apuron’s presence.

Back on Guam

Of the 13 child sex abuse suits currently sitting in Guam’s courts, four name Apuron, six name Brouillard, one names Anderson, and another names Cruz.

While Apuron has maintained his innocence of the accusations made against him, Brouillard has openly admitted in written and video documentation that he abused at least 20 boys during his tenure on Guam in the 1960s and 70s. Anderson, who court documents state resides in the mainland U.S., has not been located, and Cruz is deceased.

Connecting Brouillard to the accusations of abuse is a foregone conclusion, but making the connection to Apuron, Anderson, the Archdiocese, any of the five unnamed insurance companies, or 45 unnamed individuals will be an uphill battle for attorney David Lujan, who must establish a preponderance of evidence in multiple cases for events that allegedly transpired decades prior.

As the plaintiff in the cases, Lujan will be tasked with the burden of proof. As legal sources explain, that burden tends to become increasingly difficult with the passage of time.

Further, there is an additional hurdle that could potentially obstruct proceedings.

Given the contentiousness with which these cases have been publicized and the reach that such publicity has had within Guam’s relatively small community, there is a reasonable chance that establishing an unbiased jury will prove difficult. In fact, a number of Superior Court of Guam judges have already recused themselves from some of the 13 cases filed for reasons of familiar relationship with individuals somehow tied to the cases.

According to Post files, Judge Anita Sukola went so far as to cite exposure to the case via the church she attends, as well as her personal relationship with Apuron, as grounds for her recusal.

A number of judges have already filed disqualification memoranda in the cases, according to Gloria Lujan Rudolph of the firm Lujan & Wolff, LLP.

Rudolph, an attorney with the firm that represents the 13 existing claimants, told the Sunday Post that, so far, “Judge Pro Tempore Ingles, Judges Perez, Cenzon, Iriarte, Lamorena, and Sukola have recused themselves from at least one of the child sex abuse cases against the Church.”

Rudolph added that her firm had agreed to give the Archdiocese extra time to respond to the complaints that have already been served.

Once the complaints have been answered and the jury trials commence, counsel will have to determine, as stipulated in each of the 13 suits, the sum of the general, special, and other damages, including attorney’s fees, that will comprise the plaintiffs’ request for relief.

While such a sum cannot be easily ascertained, Post files concerning the fate of former Guam priest Rev. Andrew Mannetta state that in January 2007, the Catholic Diocese of Honolulu reached an out-of-court settlement with Elton Killion, who accused Mannetta of sexually abusing him from 1997 to 2001 during a time that Killion was a minor. The church paid out $375,000.

While none of the current 13 suits are related or equivalent to Killion’s 2007 suit, if the $375,000 figure is used as a benchmark, then the Archdiocese of Agaña, as of now, could stand to lose upwards of $4.5 million and be forced to sell some of its more valuable, and contentious, properties to make those payments.

Complete Article HERE!