— U.S. Catholic readers weigh in on how queer theology informs their faith.

By Caleb Murray

Growing up in a conservative evangelical church, the closest I came to understanding queer theology was in narrow, binary terms. Queer theology was theology that debated whether or not the Bible approved or disapproved of queer people. The boundary lines of queer theology mirrored other hot button issues (Abortion—good or bad? Homosexuality—good or bad?). The parameters of what counted as “queer” theology were so narrow (and laser-focused on sexual ethics) that the theological inquiry was effectively drained of all nuance; queer theology was reduced to a moral either/or.

As a straight, heterosexual teenager, I didn’t see myself in these debates, but I did have the nagging sense that—like the abortion debate—the militant my-side-is-right-ism was shortchanging a fascinating and complicated field. This leads me to an intentionally cheeky and provocative claim: There should be no “queer theology,” because all theology is queer. This statement may appear oxymoronic, self-defeating, or something else entirely. I say this not to erase a subfield of theological inquiry, but to reframe an entire field.

All theology is queer. So long as queerness stands for difference, inclusion, and creative upheaval, I will stand by my strange proclamation that all theology is, was, and will continue to be queer.

Scripture and millennia of interpretive tradition have revealed a queer God—a strange God, a mysterious God, a God of radical difference. In the incarnation, God obliterates metaphysics, mixing immanence and transcendence, spirit and matter. In the Eucharist, Catholics affirm a queer belief that accident, substance, and essence are transubstantiated. In mystical prayer, theologians have long queered and (mis)gendered the soul.

But what really is “queer?” Much like the concepts, identities, and orientations that it circumscribes, queerness is broadly and diversely defined by activists and academics alike. Difference (and difference of opinion) is all but baked into what it means to be queer and to define queer. To put it bluntly, for theorists and theologians, activists and self-identifying queer folks, queerness does not come with a one-size-fits-all definition.

Many thinkers and activists have shown how queerness might function as a creative or alternative mode of seeing and experiencing the world. Many philosophers, theologians, and gender theorists define queerness in opposition to the “norm”: For example, if heterosexuality is normative (the default social “norm”), then queerness is understood in the inverse (non-normative, countercultural, or transgressive). Such thinkers have argued quite convincingly that there’s a “problem with normal”: Try defining “normal” heterosexuality in a manner that would include every “straight” person, and you quickly realize that there is no stable category we might confidently label “normal.” Is a celibate, cisgender, heterosexual priest “normal?” Is it “unnatural” for a dad to raise his children while his wife works?

With questions such as these, one quickly realizes that there is no unitary “normal” out there. The observable reality of difference and diversity in the world pops the “normal” bubble. Queerness turns “normal” on its head and teaches us that none of us are very “normal,” and that is a good thing.

If queerness is about more than just same-sex attraction, what is queer theology? For many religious scholars, queer theology is—to put it simply and broadly—theology about queer people. As the theologian Linn Tonstad summarizes, “Queer theology [often] indicates theologies in which 1) sexuality and gender are discussed 2) in ways that affirm, represent, or apologize for queer persons.” Theologians, especially those who write and think along the lines of queer theology, ought to reaffirm the breadth of what queerness is and can be.

Queer theology isn’t just about gay and lesbian people; queer theology isn’t just about non-heterosexual sexual ethics; queer theology isn’t just about contemporary gender politics. Queer theology—if approached capaciously and with humility—is disruptive, creative, and new. Queer theology challenges us to look differently. Queer ways of thinking, inquiring, and arguing might undercut the very logic that attempts to demarcate, bracket, and contain Christian discourse. In useful, productive, or surprising ways, queer modes of knowing might destabilize rigid categories and stultifying traditions. Shouldn’t all theology do this? Doesn’t God exceed every feeble category we create? To pigeonhole queer modes of knowing to the self-contained box labeled “queer theology” is to shortchange Christian theology writ large.

To push this argument a step further, I do not think that theologians ought to merely “queer” theology by finding apologetic examples of homosocial belonging or same-sex love in church history and doctrine; they must acknowledge with humility and embrace with earnestness the possibility that Christian theology is always already queer.

Within scripture and the Christian tradition, readers may find apologetic resources, passages that affirm queer existence, and arguments of acceptance. For example, Romans 8:38 reminds us that nothing can separate us from God’s love. In Psalm 139 the poetic speaker declares that God knows everything about God’s creation, that God created humanity with love and intention, and that God will never abandon anyone. In no uncertain terms, 2 Corinthians 5:19 presents a theology of absolute forgiveness and generous reconciliation—ours is not a scorekeeping God, and in Christ God “no longer count[s] people’s sins against them.” But I am after something other than arguments of rebuttal.

To be clear, these are good resources, and I believe Bible verses that unequivocally affirm a God of infinite love and forgiveness eclipse the various passages pulled by bigots about pre-Judaic marriage law or the direction of fabric warp and weft. But this is just the tip of the iceberg. In my estimation, arguments of rebuttal represent a fraction of what queerness can do for Christian thought and practice. So, with this definition of queer in mind, is it really possible that all Christian theology is queer?

It is difficult to approach scripture and the Christian tradition from outside of “normal.” Indeed, the church has an entire category for the maintenance of normality and tradition: orthodoxy. Orthodoxy draws a line between things that are normal and things that are not—things that are inside the fold and things that are beyond the pale. However, if we try to read the Bible and experience the Christian tradition with new eyes and open hearts—our vision and attachment not yet bound by orthodoxy—we are reminded that Christianity and its sacred texts are often rather strange, abnormal, countercultural, and transgressive.

Reread the Beatitudes and they start to sound a little queer. Reconsider the Trinity and you start to see something homosocial or even homoerotic in its structure of mutuality and God’s self-desire for God’s self. Contemplate the sacred mystery, which revolves around transubstantiation, and you might catch a glimpse of an ineffable God who makes a habit of shattering our categories and expectations.

For hundreds of years Christians have gendered the soul. From medieval mystics to Protestant reformers, the male soul has often been theologized as feminine so that the soul might pursue a heterosexual union with Christ the bridegroom. If one’s sex, gender identity, and gender expression are thoroughly embodied, then it takes some mental gymnastics to “gender” the soul. Again, something queer is going on here. In order to avoid a gay spiritual union with Christ, there is a long tradition of cisgender men affirming the transgender status of their souls. Just as souls might transmigrate from earthly to heavenly bodies, the selective gendering of the embodied soul throws a queer wrench into the way things work. What is the line between material things and ideal objects? Where does spirit end and matter begin? Does the human man’s “female” soul retain its feminine identity, even after the man’s earthly, bodily death?

Queerness haunts the New Testament. Some might argue that Jesus and his male disciples share homosocial bonds—instances of camaraderie and same-sex intimacy, kisses, and declarations of love and fealty. But much of this is anachronistic, a ham-fisted projection of contemporary gender and sexuality categories onto misunderstood history.

But this cuts both ways. Categories are not static. Words and meanings shift over time. Take the creation myths for example. Genesis gives us two conflicting accounts of creation. In one telling, God creates a singular, androgynous human. In another, God creates Man and Woman. This certainly says something about the theological rigor of the “it’s Adam and Eve, not Adam and Steve” polemicists who pick a few passages from Genesis while ignoring neighboring paragraphs. Queer theology should not fall for the same reductionism. Instead, queer theology should champion complicated, conflicting, and category-busting inquiry.

Queer theology isn’t about cherry-picking passages that support one’s agenda while ignoring verses that don’t. Indeed, there are passages of scripture that do not square with contemporary LGBTQ politics. I am not after a simple apologetics that “prove” the moral acceptability of certain gender identities and sexual preferences once and for all. Queer theology, as a broader project, should encourage creative, surprising, and even upsetting ways of looking at scripture and tradition.

Queerness—its categorization and its conventions, its advocates and its malcontents—has much to offer Christian thought and practice. The apologists and the bigots will continue to lob their scripture verses at each other, but it is my hope that sincere followers of Christ will listen to queerness’s countervailing promise. It is the promise of approaching things differently, seeing old ideas in a new light, reencountering ancient practices with an openness to renewed life and a future marked by greater justice, lasting peace, and unbridled love. Christ’s ministry witnesses to the queer workings of the divine. His message is and was disruptive, contrarian, and mystifying. Christ’s message to his contemporaries speaks to us today: What you take to be normal might just be average. Don’t settle, you deserve abundant life.

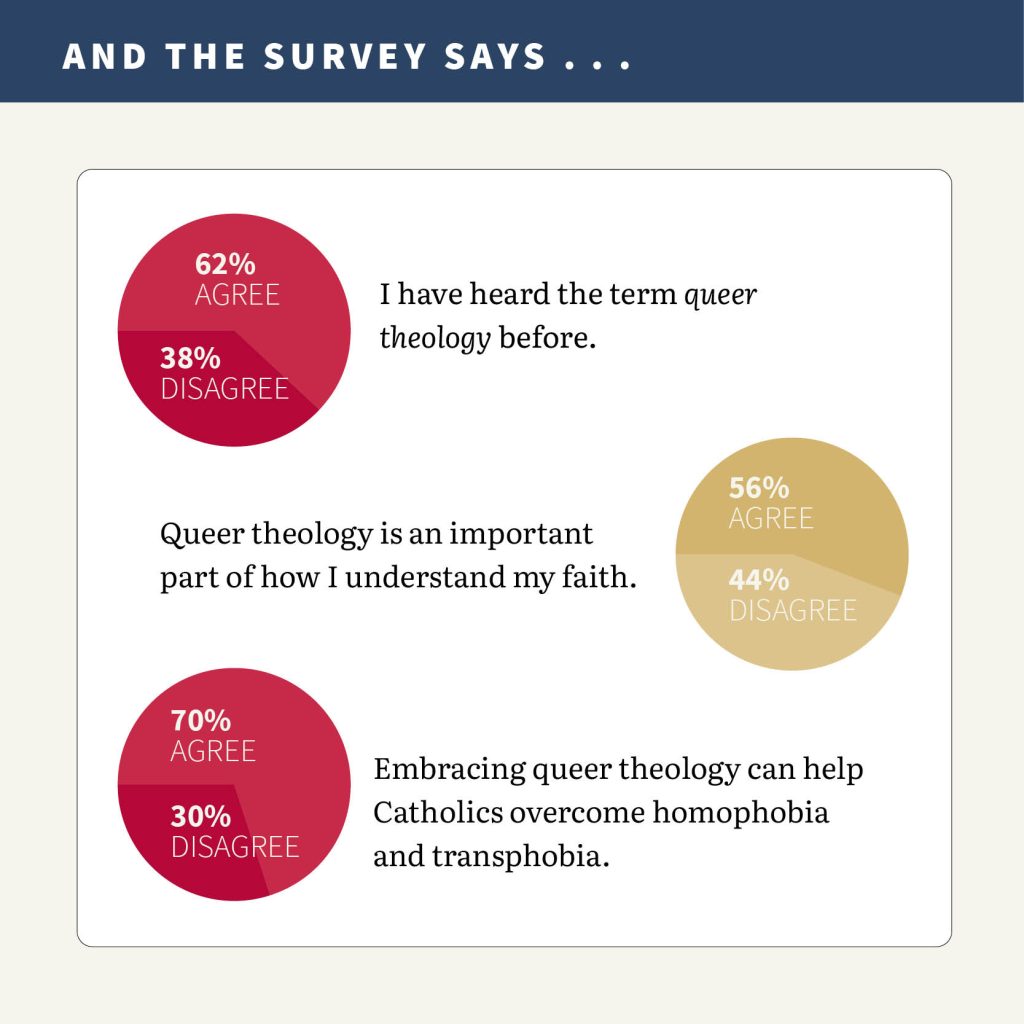

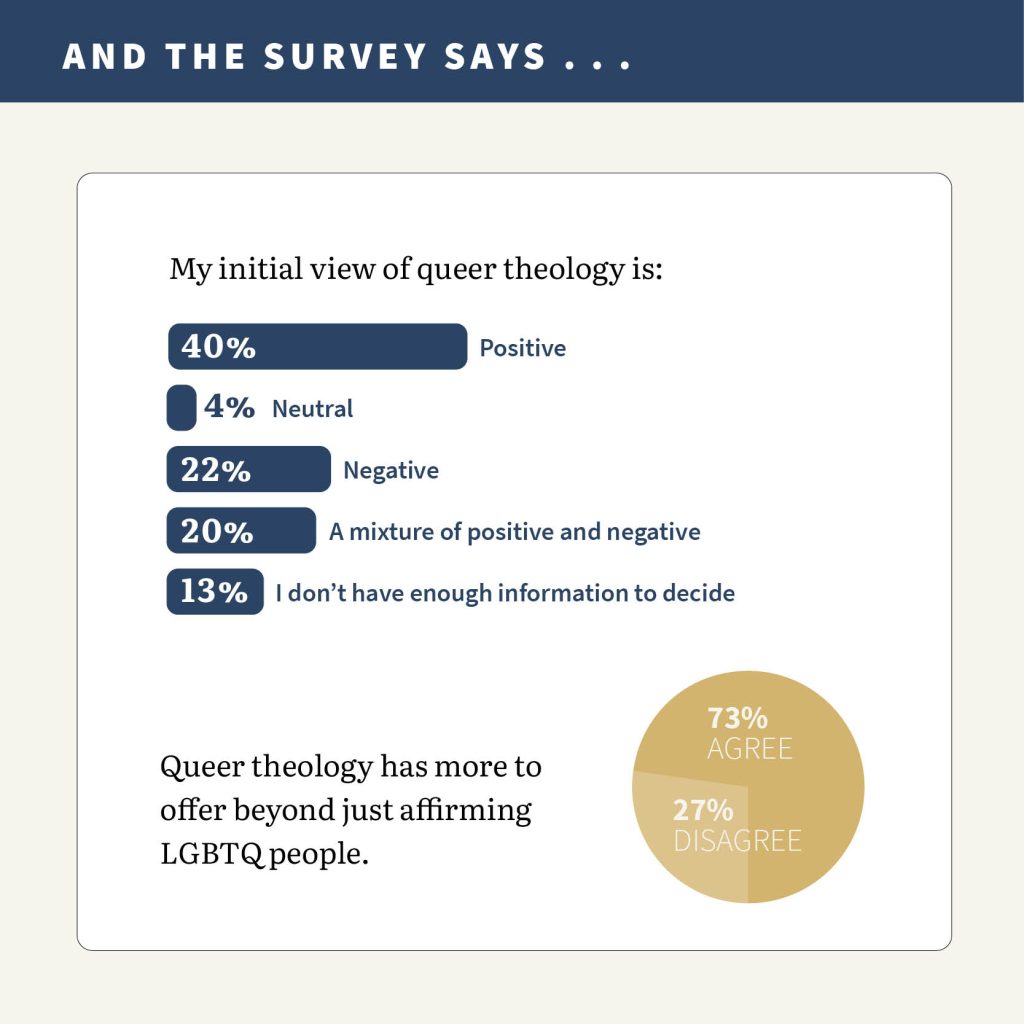

Results are based on survey responses from 113 uscatholic.org visitors.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!