Vatican stunned by Irish embassy closure

Catholic Ireland’s stunning decision to close its embassy to the Vatican is a huge blow to the Holy See’s prestige and may be followed by other countries which feel the missions are too expensive, diplomatic sources said on Friday.

The closure brought relations between Ireland and the Vatican, once ironclad allies, to an all-time low following the row earlier this year over the Irish Church’s handling of sex abuse cases and accusations that the Vatican had encouraged secrecy.

Ireland will now be the only major country of ancient Catholic tradition without an embassy in the Vatican.

“This is really bad for the Vatican because Ireland is the first big Catholic country to do this and because of what Catholicism means in Irish history,” said a Vatican diplomatic source who spoke on the condition of anonymity.

He said Ireland informed the Vatican shortly before the announcement was made on Thursday night.

Dublin’s foreign ministry said the embassy was being closed because “it yields no economic return” and that relations would be continued with an ambassador in Dublin.

The source said the Vatican was “extremely irritated” by the wording equating diplomatic missions with economic return, particularly as the Vatican sees its diplomatic role as promoting human values.

Diplomats said the Irish move might sway others to follow suit to save money because double diplomatic presences in Rome are expensive.

It was the latest crack in relations that had been seen as rock solid until a few years ago.

DAMNING REPORT

In July, the Vatican took the highly unusual step of recalling its ambassador to Ireland after Prime Minister Enda Kenny accused the Holy See of obstructing investigations into sexual abuse by priests.

The Irish parliament passed a motion deploring the Vatican’s role in “undermining child protection frameworks” following publication of a damning report on the diocese of Cloyne.

The Cloyne report said Irish clerics concealed from the authorities the sexual abuse of children by priests as recently as 2009, after the Vatican disparaged Irish child protection guidelines in a letter to Irish bishops.

While Foreign Minister Eamon Gilmore denied the embassy closure was linked to the row over sexual abuse, Rome-based diplomats said they believed it probably played a major role.

“All things being equal, I really doubt the mission to the Vatican would have been on the list to get the axe without the fallout from the sex abuse scandal,” one ambassador to the Vatican said, on condition of anonymity.

Cardinal Sean Brady, the head of the Catholic Church in Ireland, said he was profoundly disappointed by the decision and hoped the government would “revisit” it.

“This decision seems to show little regard for the important role played by the Holy See in international relations and of the historic ties between the Irish people and the Holy See over many centuries,” Brady said in a statement.

The Vatican has been an internationally recognized sovereign city-state since 1929, when Italy compensated the Catholic Church for a vast area of central Italy known as the Papal States that was taken by the state at Italian unification in 1860.

It has diplomatic relations with 179 countries. About 80 have resident ambassadors and the rest are based in other European cities.

The Vatican guards its diplomatic independence fiercely and in the past has resisted moves by some countries to locate their envoys to the Holy See inside their embassies to Italy.

Dublin said it was closing its mission to the Vatican along with those in Iran and East Timor to help meet its fiscal goals under an EU-IMF bailout. The closures will save the government 1.25 million euros ($1.725 million) a year.

Complete Article HERE!

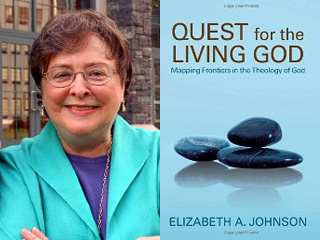

Bishops again blast nun’s popular book about God

The nation’s Catholic bishops again condemned a prominent nun’s book about God, in a move that may further fray relations between the hierarchy and Catholic theologians.

Given the popularity of Sister Elizabeth Johnson’s, “Quest for the Living God” in parishes and universities, the bishops’ renewed criticism may not help their, credibility in the pews, either.

The 11-page statement issued Friday (Oct. 28) by the bishops’ Committee on Doctrine reaffirms a March declaration that Johnson’s book “does not sufficiently ground itself in the Catholic theological tradition as its starting point.”

Johnson, a professor of systematic theology at Fordham University in New York and a member of the Congregation of St. Joseph religious order, published “Quest for the Living God” in 2007. It was widely hailed for elaborating new ways to think and speak about God within the framework of traditional Catholic beliefs and motifs.

In fact, “Quest for the Living God” became so popular that many Catholic universities began using it as a textbook, a development that sparked concern among conservatives, who have been gaining influence within the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops.

On Friday, Johnson said she read the bishops’ latest condemnation with “sadness” and “disappointment.”

“I want to make it absolutely clear that nothing in this book dissents from the church’s faith about God revealed in Jesus Christ through the Spirit,” Johnson said in a statement.

Johnson also said the bishops had not responded to her explanations and did not respond to her offer to meet with the doctrinal committee to discuss their differences.

A spokesperson for the bishops said Washington’s Cardinal Donald Wuerl, head of the doctrine committee, had offered to meet with Johnson.

The 21-page critique that the nine bishops on the doctrinal committee released last March puzzled many experts and observers because the criticisms did not seem to reflect the contents of Johnson’s book.

The bishops’ critique claimed that Johnson did not pay sufficient heed to Catholic traditions or did not argue hard enough on behalf of those traditions. The bishops also said that Johnson used ambiguous terms that were open to misinterpretation and could lead believers astray. Particularly, the bishops took issue with Johnson’s discussion of female images for God without giving sufficient weight to the primacy of male imagery.

The USCCB’s criticism irked Catholic theologians because it came without warning more than three years after the book was published and seemed to violate the bishops’ own guidelines, which call for dialogue with theologians rather than public pronouncements.

Those guidelines had been adopted in an effort to try to ease growing tensions between theologians and the hierarchy. Church officials said the popularity of Johnson’s book made it imperative that they act without wider consultations.

In addition, there were concerns because the top staffer at the doctrine committee, the Rev. Thomas Weinandy, is a conservative theologian who had long been associated with a controversial Catholic community in Washington.

In a May speech, Weinandy said that theologians can be a “curse and affliction upon the church.” He did not mention Johnson by name but blasted theologians who “often appear to possess little reverence for the mysteries of the faith as traditionally understood and presently professed within the church.”

In June, Johnson responded to the doctrinal committee with a 38-page defense of her work, arguing that the bishops had misunderstood and “misrepresented” her book.

The critique by the bishops does not mean that Johnson’s book is formally banned from parishes and universities, though it will likely become a marker for conservative critics if they see priests or theologians using the book in churches and classrooms.

And as often happens in these cases, the hierarchy’s disapproval has actually made the book even more popular than it was before.

In her statement Friday, Johnson said she received thousands of messages of support from readers after the condemnation was published in March, including one from an elderly Catholic man who had read “Quest for the Living God” in his parish book club.

“Now I am no longer afraid to meet my Maker,” the man told Johnson.

Complete Article HERE!

Justice Scalia speaks for himself on death penalty, not the Catholic Church

That Justice Antonin Scalia believes in execution as a moral form of punishment is a well-known fact. That he is an observant, traditional Roman Catholic is, similarly, well-known.

That he appears to believe his church supports the death penalty and that he’s willing to stake his job on that conviction is nothing short of astonishing. But there it is: “If I thought that Catholic doctrine held the death penalty to be immoral, I would resign,” he told an audience at Duquesne University Law School last month. “I could not be part of a system that imposes it.”

Let’s start with Scalia’s implication that the Roman Catholic Church supports the death penalty. The evidence to the contrary is overwhelming. In 2005, the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops released a statement saying that “ending the death penalty would be one important step away from a culture of death and toward building a culture of life.” In 2007, the Vatican said that capital punishment is “an affront to human dignity.” Both Pope Benedict XVI and his predecessor, John Paul II, have consistently voiced their opposition to the death penalty and praised governments and leaders who abolished it.

In 2007, Benedict sent a letter through an emissary pleading for clemency in the Georgia capital case of Troy Davis. On Sept. 21, the U.S. Supreme Court denied Davis’s petition for a stay of execution and Davis was killed by injection. One doesn’t know how Scalia voted. But in any case, that justice’s professional and democratic obligations overrode the express wishes of his pope that night.

Scalia might argue that the statements and pleas cited above are just that, statements and pleas reflecting a current mood. And he would be right. Bishops, Vatican officials and even popes say and write many things that are important or illuminating but do not qualify as doctrine, according to the law of the church. Scalia might argue further, as he has done in the past, that he is as traditionalist in his approach to religious interpretation as he is to the Constitution and that Catholic tradition has long endorsed capital punishment. Paul, Augustine, Thomas Aquinas and Thomas More — all these saints — he has argued, believed in punishment by death.

On the question of doctrine, though, Scalia is out on a limb, and like a cartoon bunny, he’s sawing it off behind him. In 1995, Pope John Paul II issued an encyclical — an official document of the utmost importance — called “Evangelium Vitae,” in which he weighed in on the death penalty.

“The nature and extent of the punishment,” he wrote, “ought not to go to the extreme of executing the offender except in cases of absolute necessity: in other words, when it would not be possible to defend society.” In today’s societies, the pope said, “such cases are very rare, if not practically non-existent.”

Death penalty opponents celebrated, saying that “Evangelium Vitae” voiced the church’s near total opposition to capital punishment. Although important theologians disagreed, saying the encyclical falls short of calling the death penalty immoral, Scalia was not one of them.

In a 2002 speech at the University of Chicago, Scalia said “Evangelium Vitae” reversed centuries of Catholic tradition by making capital punishment — his word — “wrong.”

“I do not agree with ‘Evangelium Vitae,’ ” he said, “that the death penalty can only be imposed to protect rather than avenge, and that since it is, in most modern societies, not necessary for the former purpose, it is wrong.”

And so, after consultation with canonical experts, who advised him that the doctrine was nonbinding, Scalia — his words, again — “rejected it.”

To recap: The U.S. bishops oppose capital punishment. So do this pope, the last pope and documents from the Vatican press office. Catholic doctrine isn’t crystal clear, but Scalia himself believes “Evangelium Vitae” fails to support capital punishment. And so, in the tradition of millions of Catholics for thousands of years, he has rejected official teaching in favor of his own view, which he believes (to be presumptuous for a minute) to be more traditional and more moral than the established one.

That’s fine with me. I don’t want a justice sitting on the Supreme Court who submits blindly to religious authority or who holds his religion above the laws of the land. So keep your job, Justice Scalia. Just don’t pretend your church approves of the death penalty. Or that you aren’t like most people of faith, cherry-picking the teachings of your church that suit you best.

Complete Article HERE!

“Idolizer of the Market”: Paul Ryan Can’t Quite Hear Catholic Church’s Call for Economic Justice

Paul Ryan accuses President Obama of engaging in “sowing social unrest and class resentment.” The House Budget Committee chairman says the president is “preying on the emotions of fear, envy and resentment.”

Paul Ryan accuses Elizabeth Warren of engaging in class warfare. The House Budget Committee chairman the Massachusetts U.S. Senate candidate is guilty of engaging in the “fatal conceit of liberalism.”

But what about the Catholic Church, which has taken a far more radical position on economic issues than Obama or Warren? What does the House Budget Committee chairman, a self-described “good Catholic,” do then?

If you’re Paul Ryan, you don’t decry the church for engaging in class warfare. Instead, you spin an interpretation of the church’s latest pronouncements that bears scant resemblance to what’s been written — but that just happens to favor your political interests.

Ryan’s certainly not the only Catholic politician in Washington to break with the church.

For years, Catholic Democrats from House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi to Massachusetts Senator John Kerry to former House Appropriations Committee David Obey have taken their hits for adopting positions that are at odds with the church’s teachings with regard to reproductive rights and same-sex marriage.

But many of the same politicians who align with the church on social issues are at odds with the social-justice commitment it brings to economic debates.

Ryan’s rigidly right-wing approach to issues of taxation and spending, as well as his deep loyalty to Wall Street (he led the fight to get conservatives to back the 2008 bank bailout), has frequently put him at odds with the church’s social-justice teaching.

But never has the distinction been more clear than in recent days, as Ryan’s statements have reemphasized his status as the leading congressional spokesman for policy positions that are dramatically at odds with those expressed in a major new statement by the Vatican’s Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace?

That puts the congressman in a difficult spot.

Ryan has always identified as a Catholic politician, and he has frequently suggested that he is guided by the teachings of the church, going so far as to write in a July, 2011, column for a Catholic publication that: “Catholic social teaching is indispensable for officeholders.”

So what, Ryan was asked after the release of the Pontifical Council’s statement, did the House Budget Committee chairman think of proposals that the Rev. Thomas Reese of Georgetown University’s Woodstock Theological Center suggests are “closer to the views of Occupy Wall Street than anyone in the U.S. Congress”

Time magazine observes that: “Those politicians who think the Dodd-Frank law went too far in attempting to reform Wall Street will likely need smelling salts after taking a look at a proposal for reforming the global financial system that was released by the Vatican… Calling into question the entire foundation of neo-liberal economics and proposing one world financial order? You never know what those radicals over at the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace will come up with next.”

So what was Paul Ryan’s take?

What did the chairman of the House Banking Committee think of the Pontifical Council’s highlighting of Pope John Paul II’s criticism of the “idolatry of the market”? What of the council’s call for “the reform of the international monetary system and, in particular, the commitment to create some form of global monetary management” that will end abuses and inequity and restore “the primacy of the spiritual and of ethics needs to be restored and, with them, the primacy of politics – which is responsible for the common good – over the economy and finance”?

Ryan’s initial response to a pointed question about whether the church, with urging of “the global community to steer its institutions towards achieving the common good,” might be engaging in the “class warfare” he so frequently decries, was to try and laugh the contradictions off.

“Um, I actually do read these,” Ryan joked, with regard to Pontifical pronouncements. “I’m a good Catholic, you know… get in trouble if I don’t.”

Pressed to actually answer the question, the usually direct and unequivocal Ryan suddenly embraced moral relativism.

“You could interpret these in different ways,” he said of the statements from the church’s hierarchy. “I think you could derive different lessons from it,” he added.

Amusingly, the congressman then took a shot at moral relativism, suggesting that when the Pope expresses concern regarding the global financial system he is “talking about the extreme edge of individualism predicated upon moral relativism that produces bad results in society for people and families, and I think that’s the kind of thing he is talking about.”

That’s an interesting statement coming from a congressman who frequently mentions his reverence for Ayn Rand, the novelist who set herself up as a high priestess of individualism.

It’s also wrong.

The statements from the Pope and the Pontifical Council have been focused and clear in their criticism of the greed and abuse that characterizes the current financial system, of their concerns about the economic inequity its has spawned, and especially about the damage done to the poor by the “idolatry of the market.”

The Pontifical Council is calling for dramatically more oversight and regulation of financial markets, and for the establishment of new public authorities “with universal jurisdiction” to provide “supervision and coordination” for “the economy and finance.”

“These latter (economy and finance) need to be brought back within the boundaries of their real vocation and function, including their social function, in consideration of their obvious responsibilities to society, in order to nourish markets and financial institutions which are really at the service of the person, which are capable of responding to the needs of the common good and universal brotherhood, and which transcend all forms of economist stagnation and performative mercantilism,” the council continues. “On the basis of this sort of ethical approach, it seems advisable to reflect, for example, on… taxation measures on financial transactions through fair but modulated rates with charges proportionate to the complexity of the operations, especially those made on the ‘secondary’ market. Such taxation would be very useful in promoting global development and sustainability according to the principles of social justice and solidarity. It could also contribute to the creation of a world reserve fund to support the economies of the countries hit by crisis as well as the recovery of their monetary and financial system…”

That’s a reference to a financial speculation tax, something that Ryan — a major recipient of campaign contributions from traders, hedge-fund managers and other Wall Street insiders — has historically opposed.

The Pontifical Council says that such a tax should be considered “in order to nourish markets and financial institutions which are really at the service of the person, which are capable of responding to the needs of the common good and universal brotherhood, and which transcend all forms of economist stagnation and performative mercantilism.”

There is no moral relativism in that statement, no list of options. Rather, there is a call from the Catholic Church for the development of an economy and financial systems “capable of responding to the needs of the common good and universal brotherhood.”

I happen to agree with the church on this one. My sense is that my friend Paul Ryan does not.

America is not a theocracy. Ryan certainly has a right to deviate from church doctrine as he chooses. But, hopefully, he will recognize that he is, like those members of Congress who support reproductive rights or same-sex marriage, distancing himself from the position of the church.

He is free to do so, of course. But those of us who understand that budgets are moral documents — which outline the values and priorities of a society — are equally free to wonder whether Paul Ryan, as chairman of the House Budget Committee, is perhaps engaging too ardently in the “idolatry of the market.”

Complete Article HERE!