Canada’s Indigenous communities have long sought a papal apology for the church’s role in a system of forced assimilation at schools where abuse and disease were widespread.

By Ian Austen and Vjosa Isai

Pope Francis will meet with Indigenous leaders later this year to discuss coming to Canada to apologize for the church’s role in operating schools that abused and forcibly assimilated generations of Indigenous children, a step toward resolving the grievances of survivors and Indigenous communities, the head of Canada’s largest Indigenous organization said on Wednesday.

In a statement, the Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops said that the pope will meet separately at the Vatican with the representatives of Canada’s three biggest Indigenous groups — the First Nations, the Métis and the Inuit — during a four-day series of meetings in December that will culminate in a joint session with all three.

“Pope Francis is deeply committed to hearing directly from Indigenous Peoples, expressing his heartfelt closeness, addressing the impact of colonization and the role of the Church in the residential school system,” the bishops wrote.

Canada’s Indigenous leaders have long called for a papal apology for the church’s role in the residential schools, a government-created system that operated for about 113 years and that a National Truth and Reconciliation Commission called “cultural genocide.”

Those calls have intensified since May, following announcements by three Indigenous communities that ground penetrating radar has revealed many hundreds of unmarked graves containing human remains, mostly of children, at the sites of former schools in British Columbia and Saskatchewan. While both disease and violence were widespread at the schools, the scans offer no information about how the children died.

Catholic orders ran about 70 percent of the schools on behalf of the government. Despite a direct plea from Prime Minister Justin Trudeau in 2017, the pope has consistently refused to apologize for the church.

Three Protestant denominations that also ran residential schools apologized long ago and contributed millions of dollars to settle in 2005 a class-action suit brought by former students.

The Catholic Church, however, has since raised less than four million Canadian dollars, or $3.2 million, of its 25 million dollar share of the settlement.

The delegation of Indigenous leaders will push the question of compensation at the Vatican meetings, said Perry Bellegarde, national chief of the Assembly of First Nations, Canada’s largest Indigenous organization. However, their focus will be on persuading the pope to come to Canada to apologize.

“The Vatican and the Roman Catholic Church, they’ve made apologies to the Irish people, they made apologies to the Indigenous people of Bolivia,” Chief Bellegarde told a news conference. “So I think the spirit will move in the appropriate way at the appropriate time.”

The news of the Vatican meeting came as the third Canadian Indigenous community announced on Wednesday that it had found 182 human remains near a former school for Indigenous children run by the Catholic church.

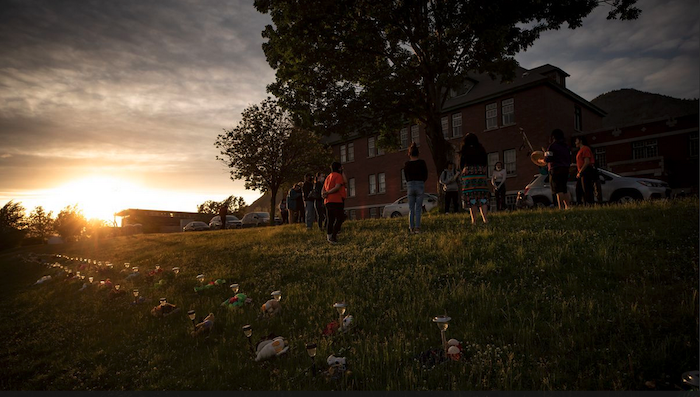

At the St. Eugene’s Mission School, located in British Columbia on the land of a First Nation which renders its name as ʔaq’am, Indigenous leaders said that a search that started last year has found 182 unmarked graves, some of them just three to four feet deep.

Chief Bellegarde said that the Indigenous groups had been trying for two years to schedule this meeting with the pope. But he said that it remains unclear which, if any, of their requests that the pope will agree to.

“There are no guarantees of any kind of apology or anything coming forward, there’s no guarantee that he’ll even come back to Canada,” Chief Bellegarde said. “But we have to make the attempt and we have to seize the opportunity.”

A national Truth and Reconciliation Commission found that physical, mental and sexual abuse were common at the schools, which operated for over 100 years, starting in the late 19th century. Many of the schools were overcrowded, their children afflicted by disease and, in some cases, malnutrition. All of them rigorously, and sometimes violently, enforced prohibitions on Indigenous languages and cultural practices.

In May, Canadians were shocked to learn that ground penetrating radar had revealed the remains of 215 people, mostly children, near the former Kamloops Indian Residential School in British Columbia.

Last week the shock was compounded after a First Nation in Saskatchewan said that the technology had found 751 remains at the site of a former school on its land.

The St. Eugene’s Mission School, where the discovery of remains was announced on Wednesday, was operated between 1890 and 1969 by Catholic orders, including the Oblates of Mary Immaculate.

In a statement released Wednesday, the Lower Kootenay Band said the remains likely belonged to people from the bands of Ktunaxa Nation — of which it is a member — and other neighboring Indigenous communities.

The search, which is continuing, was organized by the ?aq’am First Nation, which informed Chief Jason Louie of the Lower Kootenay Band about its initial findings last week. After making the discovery public on Wednesday, Chief Louie said that he is less interested in a papal apology than criminal charges being brought against members of the church involved in running the school.

“We’re beyond apologies, we need to talk about accountability,” he said. “If Nazi war criminals can be tried at an elderly age for their war crimes, I think we should be tracking down the living survivors of the church — being the priests and the nuns — who had a hand in this.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!