By John L. Allen Jr.

This column probably ought to carry a warning label: “The following piece of writing contains an apples-and-oranges comparison that may be hazardous to your intellectual health.” I’m going to compare two fights among senior churchmen, but the purpose is not to suggest they’re identical. Rather, it’s to understand what makes them different.

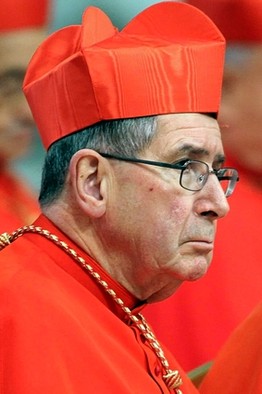

The first term of comparison is the tension between Archbishop Jose Gomez of Los Angeles and his predecessor, Cardinal Roger Mahony. On Jan. 31, Gomez announced that Mahony would “no longer have any administrative or public duties” because of failures to protect children from abuse, documented in files released by the archdiocese. That triggered an open letter to Gomez from Mahony acknowledging mistakes, but insisting he went on to make Los Angeles “second to none” in keeping children safe.

The first term of comparison is the tension between Archbishop Jose Gomez of Los Angeles and his predecessor, Cardinal Roger Mahony. On Jan. 31, Gomez announced that Mahony would “no longer have any administrative or public duties” because of failures to protect children from abuse, documented in files released by the archdiocese. That triggered an open letter to Gomez from Mahony acknowledging mistakes, but insisting he went on to make Los Angeles “second to none” in keeping children safe.

Mahony remains a priest and bishop in good standing, and he really hasn’t had any administrative role since stepping down in March 2011. The practical effect of the action thus is limited, but symbolically it amounts to what Jesuit Fr. Tom Reese has called a “public shaming.”

So far, the Vatican hasn’t said much other than it’s paying attention and clarifying that the action applies only to Los Angeles.

Behind door No. 2 lies the highly public spat in 2010 between Cardinal Christoph Schönborn of Vienna, Austria, and Italian Cardinal Angelo Sodano, a former Secretary of State and still the dean of the College of Cardinals.

For those whose memories may have dimmed, a series of clerical abuse scandals exploded across Europe in early 2010, which among other things cast a critical spotlight on Benedict XVI’s personal record. Sodano created a media sensation in April 2010 by calling that criticism “petty gossip” during the Vatican’s Easter Mass.

In a session with Austrian journalists not long afterward, Schönborn not only said Sodano had “deeply wronged” abuse victims, but he also charged that Sodano had blocked an investigation of Schönborn’s disgraced predecessor, Cardinal Hans Hermann Gröer, who had been accused of molesting seminarians and monks and who resigned in 1995. Schönborn reportedly said that then-Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, now Pope Benedict XVI, wanted to take action, but he lost an internal Vatican argument to Sodano.

Schönborn apparently thought that session was off the record, but the content leaked out anyway.

In that case, the Vatican hardly restricted itself to a dry “no comment.” Instead, Schönborn was summoned for a one-on-one with Benedict, and afterward, both Sodano and Cardinal Tarcisio Bertone, the current Secretary of State, joined the conversation. When it was over, the Vatican issued a statement widely seen as a rebuke to Schönborn — among other things, pointedly reminding him that it’s not up to him to pass judgment on a fellow cardinal.

“It should be remembered that in the church, when there are accusations against a cardinal, competence rests solely with the pope,” it said.

One might call this the “Sodano Rule”: When it comes to cardinals, keep your hands off and leave it to the boss.

Hence the obvious question: Why doesn’t the Sodano Rule apply to Gomez? So far, no one has summoned him for a knuckle-rapping session, and the Vatican declined a chance to reiterate that cardinals are accountable only to the pope. The working assumption is that Gomez informed Rome of his plans, and apparently no one asked him to back down.

I can think of six factors that might help account for the contrast.

First, Schönborn had no authority over Sodano, who doesn’t live in Vienna. Mahony, however, resides in Los Angeles, having moved back to his childhood parish of St. Charles Borromeo in North Hollywood. Moreover, Mahony had no intention of keeping a low profile. He wanted to help lead the charge in Los Angeles and nationally on immigration reform.

Canonically speaking, Gomez has the right to determine who can play public roles on behalf of the church in his own jurisdiction, even if no one probably envisioned that codicil being wielded against a prince of the church.

Second, the 68-year-old Schönborn studied under Benedict XVI when the future pope was a theology professor and is widely perceived as a papal protégé. He made his comments about Sodano in the context of defending the pope’s record. Thus the initial suspicion in many quarters was that Schönborn was speaking for the pope, that his attack on Sodano represented Benedict’s thinking, expressed through one of his closest friends and allies.

Gomez does not have the same close relationship with Benedict XVI, so there’s not the same tendency to assume he’s acting as a mouthpiece for the papal apartment. As a result, the Vatican likely doesn’t feel the same pressure to get involved.

Third, and with no disrespect to Mahony, Sodano is simply a bigger target.

Sodano was the second-most-powerful official in the church under Pope John Paul II, and he remains dean of the College of Cardinals, which means he would preside over the college when Benedict dies. Although Sodano’s reputation has taken a beating, especially over his long-running defense of the late Mexican Fr. Marcial Maciel Degollado, founder of the Legionaries of Christ, he still has a lot of Vatican friends.

Mahony, by way of contrast, is seen as a relatively liberal prelate somewhat out of sync with the ethos under John Paul II and Benedict XVI. Although he’s an active member of three Vatican departments — the Congregation for Eastern Churches, the Council for Social Communications, and the Prefecture for the Economic Affairs — he doesn’t have anything like Sodano’s base of support to push back.

Fourth, precisely because Sodano was a key aide to John Paul II, criticism of his record functions as a proxy for calling John Paul’s legacy into question. In 2010, the Vatican was preparing to beatify John Paul II, just as they’re now getting ready for his canonization. In that context, anything that smacks of tarnishing the late pope’s memory is dicey stuff, especially if the critique is perceived as coming from the sitting pope through one of his friends.

Mahony was never part of John Paul’s inner circle, so criticism of him doesn’t carry quite the same sting.

Fifth, perhaps the Vatican learned something from the way it handled things two years ago. Whatever the intent, the fact that Schönborn was hauled on the carpet came off as punishment for being outspoken about the sex abuse crisis and was taken by critics as another chapter in denial. If the Vatican were to wade in now in support of Mahony, even if the principle involved was a cardinal’s unique relationship with the pope rather than his record on abuse cases, it would probably leave a similar bad aftertaste.

Of course, the Vatican has a mixed record in terms of learning the right lessons from previous PR disasters, but maybe this is one instance in which they’ve concluded that discretion is the better part of valor.

Sixth, and most basically, the culture of the church is evolving in the direction of greater accountability. Yes, it’s happening under external pressure, and yes, it’s taking an awfully long time. Nonetheless, the wheels are slowly grinding in the direction of the idea that when someone drops the ball, there need to be consequences.

This week marks the one-year anniversary of an international summit on the sex abuse crisis at Rome’s Gregorian University co-sponsored by several Vatican departments. At that session, then-Msgr. Charles Scicluna of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith said it’s “simply not acceptable” for bishops to fail to act when reports of abuse surface, and that “we need to use the tools that canonical law and tradition give us for the accountability of bishops.” Sciculna since has been made a bishop in Malta and a member of the doctrinal congregation, and one could view the situation in Los Angeles as a trial run for Scicluna’s position.

How all this will play out isn’t clear. Vatican culture abhors public tiffs between senior prelates, fearing that it projects disunity. If the tensions between Gomez and Mahony metastasize, Rome may feel compelled to step in.

For now, however, it would seem the Sodano Rule comes with an asterisk: Only the pope can judge a cardinal — unless there are good reasons to let somebody else do it.

Complete Article HERE!

By now it is familiar news, though no less stomach-turning, that top officials in the Catholic Church protected pedophile priests for decades — impeding criminal investigations, shuffling offenders to new parishes or abroad, and resisting disclosure. In so doing, they exhibited little concern for victims of sex abuse, usually boys.

By now it is familiar news, though no less stomach-turning, that top officials in the Catholic Church protected pedophile priests for decades — impeding criminal investigations, shuffling offenders to new parishes or abroad, and resisting disclosure. In so doing, they exhibited little concern for victims of sex abuse, usually boys.