COMMENTARY

A nun who was sexually abused as a minor by a predator priest called out Monsignor William J. Lynn Thursday from her perch on the witness stand.

It was a dramatic confrontation as the Archdiocese of Philadelphia sex abuse trial wrapped up its seventh week of testimony. Lynn is on trial for allegedly conspiring to endanger the welfare of children by allowing abusive priests to continue in ministry

It was a dramatic confrontation as the Archdiocese of Philadelphia sex abuse trial wrapped up its seventh week of testimony. Lynn is on trial for allegedly conspiring to endanger the welfare of children by allowing abusive priests to continue in ministry

All along, the defense mantra has been that the monsignor was just a cog in the wheel down at archdiocese headquarters on 222 N. 17th St., and that the ultimate villain in the case was the guy who wielded the ultimate power in the archdiocese, the conveniently dead Cardinal Anthony J. Bevilacqua.

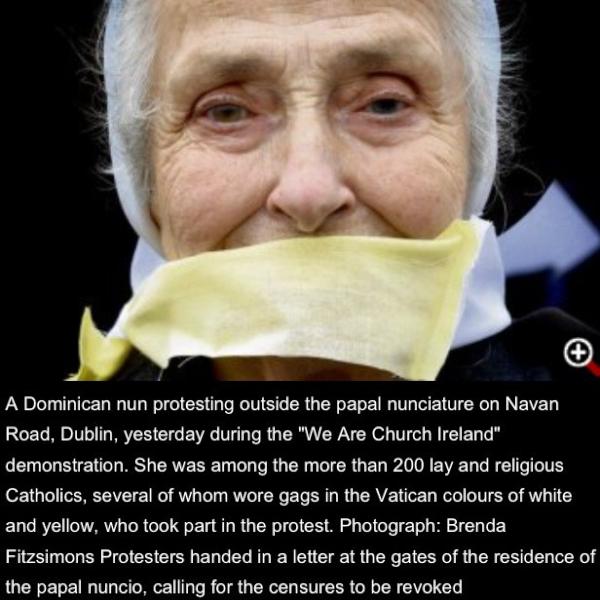

But the nun on the witness stand refused to play along.

It started when Thomas Bergstrom, a defense lawyer for Msgr. Lynn, tried to get the nun on cross-examination to agree that Msgr. Lynn did not have the power to remove a pastor who had sexually abused her and at least 10 other young women.

“He [Lynn] had the power to suggest it,” she said, referring to the removal of the pastor. And then on redirect, when the prosecutor asked her about the power Lynn had as the archdiocese’s secretary for clergy, the nun said that Lynn had the simple power of just saying no.

Instead of going along with the power structure, the nun said, “You can also say, I cannot do this.”

It was a simple, but powerful declaration coming from a nun who herself was an administrator down at archdiocese HQ, and also as a young woman, a victim of sex abuse from a pervert priest.

The nun, who did not want to be identified, wasn’t finished.

“I would think that his [Lynn’s] recommendation would be heard,”she told Assistant District Attorney Patrick Blessington. And if it wasn’t, Lynn could have told the cardinal, “I cannot go on; if it isn’t done that way, I can quit.”

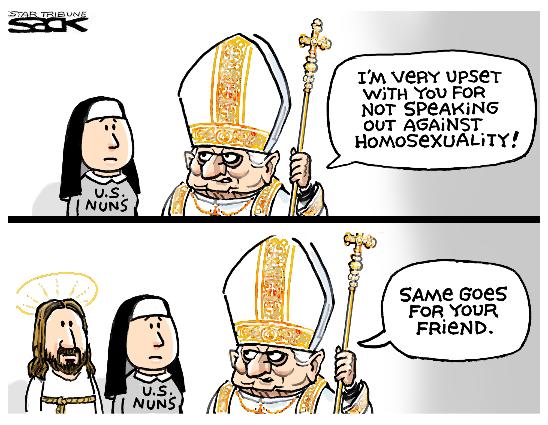

The nun’s firm but understated conviction about the need to simply do the right thing sent a ripple of excitement through courtroom spectators, which included victims of sex abuse, and activists hoping for the impossible, reform in the Roman Catholic Church. It also raised an age-old question, namely why do the women in the Catholic church usually have more balls than the men?

Before she called out the monsignor, the nun told her story about how she had been abused by the notorious Father Nicholas V. Cudemo, a serial rapist who used mind control and guilt to dominate his victims.

The nun, dubbed “Sister Irene” in the 2005 grand jury report, was Father Cudemo’s second cousin. The priest also abused the nun’s sister, and a younger cousin, in addition to at least eight other young women.

The witness was 15 years old when Father Cudemo took her to baseball and basketball games at Archbishop Kennedy High School, where the priest was a teacher. While driving her home one night, Cudemo pulled over, and started kissing her passionately. “He got on top of me,” the nun testified. “His hands were literally all over me.”

The witness told the jury that she had dated boys before, but had never experienced such “intense passion or strength.”

Then, when she was 16, it happened again. Father Cudemo drove her home, this time with a carload of other kids. While driving, he took her hand and “placed it on his penis strongly,” she said, and then he just held her hand there.

“I just went numb,” she said. Father Cudemo would call up the victim and tell her she was “his favorite cousin,” and he would explain his behavior by saying, “cousins have these kinds of relationships.”

In 1991, Sister Irene found out that Father Cudemo had sexually abused her younger cousin, identified in the grand jury report as Ruth. The abuse of Ruth began at 10, and included an abortion at 11. Sister Irene was shattered by the news.

“I really felt for the first time in my life I was confronting evil,” she told the jury. So the nun, her sister, and her cousin Ruth went to the archdiocese on Sept. 25, 1991, to report the abuse. They told Msgr. James E. Molloy, vicar for administration, and his assistant, Msgr. Lynn, that they wanted Father Cudemo removed from his post as pastor of St. Callistus Church.

Molloy told the victims, “It’s not that easy to remove a pastor at this time,” the nun told the jury. When the victims suggested the archdiocese notify parishioners at St. Callistus about what the priest had done to his victims, they were told it would be “defamation of character” and “calumny.”

Complete Article HERE!