By Cristina LH Traina

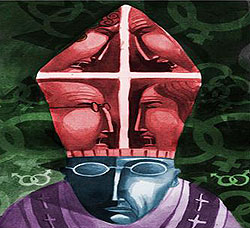

Selection of the next Pope will factor in a host of complicated variables as wings of the Church compete for ascendancy.

Pope Benedict XVI’s impending resignation has already fuelled all the usual speculation about candidates for his successor, accompanied by profiles, photos and odds of election. Behind the hoopla is the question, what sort of leader will really be best for the Church?

Pope Benedict XVI’s impending resignation has already fuelled all the usual speculation about candidates for his successor, accompanied by profiles, photos and odds of election. Behind the hoopla is the question, what sort of leader will really be best for the Church?

Benedict’s own admission that an elderly man cannot undertake the globe-trotting that effective relations require suggests that as a rule, a younger, healthier leader would be a wise choice. But the Church also faces the question what style of leadership would be most fruitful.

Despite the vision of Vatican Council II, which recommended collegial authority and granted the laity almost complete province over action in the world, Pope John Paul II’s and Pope Benedict XVI’s pontificates have echoed an ultramontane, top-down model in which the authority of the pope supersedes that of the bishops, individually or in national organisations.

History of papal power

Vatican I ratified the ultramontane model in an era in which the Roman Catholic Church felt besieged on all sides. The Church had just lost the Papal States and suffered long periods of anti-clericalism and persecution in Europe. The Council responded by absolutising the popes’ control over the one thing left to them: the Church. Over the next 50 years, popes declared a single standard of orthodoxy (the works of Thomas Aquinas) and published – and enforced – laundry lists of anathematised philosophical and political beliefs.

In earlier periods, strong central control could not be realised so easily in practice, except in cases like the Inquisition in which civil power could be conscripted. But when travel took place on foot, by horse, or by sailing ship, and all communications were carried by letter, people had to choose carefully what information to send up and down the chain of the hierarchy. Practices varied, and many “irregularities” simply went uncommented.

Flash forward to the present day, and ultramontanism becomes a little less forgiving. Photos, news reports and blog posts make their way across oceans in seconds or less. Not only does Rome have theoretical authority over every Catholic person and organisation, it has actual access to real-time information about them. This is not to belittle the silencings, excommunications, and even executions of earlier eras, or to overlook the inefficient contemporary Vatican bureaucracy, in which branches famously work at cross purposes. But strong central control combined with instant communication from every layer of the church in every corner of the world creates unprecedented micro-managerial possibilities.

Contemporary contradictions

Cue the debate over the next pope. So-called “conservative” Catholics will be cheering for a candidate who  continues Benedict’s line of strong Catholic identity. Conservatives, so the stereotype goes, will want a firm hand guiding a centralised, top-down hierarchy capable of overseeing of theology and charitable work all over the world. The ultramontane trend confirmed at Vatican I, and alive and well in the CEO model of the papacy, is their ideal.

continues Benedict’s line of strong Catholic identity. Conservatives, so the stereotype goes, will want a firm hand guiding a centralised, top-down hierarchy capable of overseeing of theology and charitable work all over the world. The ultramontane trend confirmed at Vatican I, and alive and well in the CEO model of the papacy, is their ideal.

A look back at Pope Benedict XVI’s career

In contrast, conventional wisdom says that so-called “liberal” Catholics will be hoping for a candidate who, like John XXIII 50 years ago, might surprise the world by changing direction. Liberals will want a decentralised, participatory structure that places most power in the hands of national bishops’ conferences, in collaboration with the laity. On this view, popes are good for inspiration, pastoral care and ecumenical diplomacy but too far removed from the local details of daily life to rule sensitively on regional questions.

Recent events seem to reinforce these stereotypes. Liberal Catholics took it amiss when the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (CDF) undertook a comprehensive review of the Leadership Conference of Women Religious, the largest organisation of Catholic women major superiors. The CDF judged that rampant “radical feminism”, dissent and collaboration with questionable social justice organisations needed correction, and it appointed Seattle Archbishop Peter Sartain to oversee the “renewal” of the organisation.

Liberals viewed this as an attempt to silence the most educated and independent branch of American women religious. Conservatives held up the smaller Council of Major Superiors of Women Religious, which was not investigated, as an example of fidelity and obedience.

Similarly, when Benedict blocked Lesley Anne Knight’s run for a second term as director of the Catholic umbrella organisation Caritas Internationalis and issued his motu proprio on preserving the Catholic identity of Catholic charities, liberals fretted over Catholic groups’ losses of funds and of opportunities for collaboration with independent non-profits. Conservatives, on the other hand, heralded the increased oversight as an overdue means of ensuring the purity of Catholic teaching and of income streams.

The important exception seems to be the clerical sex abuse crisis. Here organs associated with American liberal Catholicism – Voice of the Faithful, The Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests, Call to Action, BishopAccountability.org, the National Catholic Reporter and others – have echoed conservatives in demanding authoritative, decisive action from the Vatican against bishops who facilitated and hid priestly sexual abuse. Catholics in Ireland and much of Europe, not to mention other parts of the world, have joined them in this demand.

Demand for clerical accountability

And here’s the contradiction. Catholics may not be able to have their cake and eat it too. Some conservative laypeople have laid aside ultramontanism to join the liberal demand for clerical accountability to laypeople, and liberals have joined the conservative chorus requesting action from Rome. Only a tough, centralised hierarchy that monitors all of its outposts carefully can take the strong action against bishops that liberal Catholics seek. A truly collegial model – perhaps a federation of strong national churches with a single spiritual leader, as in the Anglican Communion – would yield more adaptability at the local level but would not have the central power to depose transgressing bishops.

Thus liberal Catholics face a quandary. A pope strong and authoritative enough to purge transgressing bishops is likely to use his power as well to purge liberal theologians, nuns and clergy. A pope who opts for a collegial style more in keeping with Vatican Council II’s precedent will have to rely on his fellow bishops to monitor each other, something they have so far shown little willingness to do.

Conservatives face a similar quandary. What will ensure that the strong hierarchy they envision protects laypeople from clerical transgressions?

There is a third option, of course. If the Catholic Church had structures of accountability that operated from below rather than from above, it would not need to rely on benevolent ultramontanism to get rid of destructive bishops. The next pope could undermine the Vatican’s managerial authority even more radically by insisting that bishops share power collegially with priests, vowed religious and laypeople, and by instituting term limits for bishops like those observed by many Protestant communions. Benedict XVI’s resignation could be the precedent. Stranger things have happened.

Complete Article HERE!