Two modern-day American suffragists had a plan.

During this month’s Synod of Bishops, an international gathering at the Vatican, Deborah Rose-Milavec and Kate McElwee, who lead groups dedicated to advancing women in leadership roles in the Roman Catholic Church, made sure that Cardinal Lorenzo Baldisseri, the synod’s general secretary, was presented with a hefty pink folder.

Inside was a petition with more than 9,000 signatures and one specific request: Allow female religious superiors at the synod to “vote as equals alongside their Brothers in Christ.”

The petition’s request, said Ms. Rose-Milavec, the executive director of Future Church and Ms. McElwee, who holds the same post at the Women’s Ordination Conference, was a minor volley in what has seemed to be an insurmountable battle to get the male-centric Catholic Church to pay serious attention to women, who represent about half the world’s 1.3 billion Catholics but count for little where it matters.

Vatican synods are held every few years. Women have emerged as a major concern of this one, which opened earlier this month and focuses on how the church can better minister to today’s youth in an era of emptying pews.

“The presence of women in the church, the role of women in the church,” has been repeatedly raised, in the synod’s plenary meeting and within smaller working groups, said Sister Sally Marie Hodgdon, the superior general of the Sisters of St. Joseph of Chambery, and a synod participant. “The youth bring it up, as have some of the bishops and cardinals.”

“Clearly,” she added, the issue of women will be in the final document, which will be voted on Saturday.

But women, who make up about a tenth of the 340 or so synod participants, won’t be among the voters. Until this synod, only ordained men were allowed to vote on recommendations to the working document, whose final draft is given to the pope, who can include as much as he wants in his own post-synodal reflection.

This year, though, two men who are not ordained but are the superiors general of their respective religious orders have been granted the right to vote. Sister Hodgdon, too, is a superior general, but she has no voting rights.

For some Catholics, the difference clearly smacks of the sexism that “underlines the grave marginalization of women in the church,” said Lucetta Scaraffia, the editor of a monthly insert on women in the Vatican’s newspaper, L’Osservatore Romano. “It’s a clamorous injustice. It demonstrates that the criteria they use is not between priest and lay people, but between women and men,” she said.

The cover of the October insert, “Women, Church, World,” depicted a woman shouting angrily. The intent of the issue, Ms. Scaraffia said, was to encourage debate and to get women “to protest every time there is a reason to protest.”

“What are they afraid of? One woman voting, honestly!” said Ms. McElwee, of the Women’s Ordination Conference, who helped to draft the petition and was an organizer of a protest that coincided with the synod’s opening, on Oct. 3.

Standing outside the gates that lead to the synod hall inside Vatican City that day, several dozen women and men chanted: “Knock, knock.” “Who’s there?” “More than half the church.” The protest was peaceful — “a prayer groups is more disruptive,” Ms. McElwee said — but still drew the attention of the police, who brought the protest to a halt, identified all the protesters and forced some to delete footage of the demonstration from their mobile phones

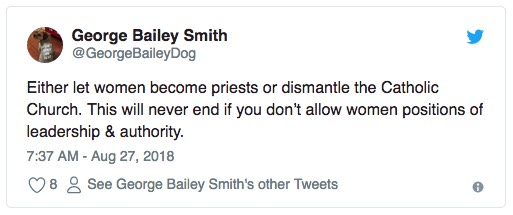

The petition to allow female superiors general a synod vote was a “strategic” move toward their more equal participation in church matters, Ms. McElwee said, adding that she realized it confirmed the “ultimate fear” of some clerics who see it as a step down a “slippery slope that could eventually lead to women’s ordination” as priests.

Such ordination, Ms. McElwee said, was “the last door that’s closed to women,” though there are many doors in between. Church teaching says that women can’t be priests because Jesus chose only men as his apostles.

Various studies of religious affiliation in the United States show that young people are leaving the Catholic Church in greater numbers than before for many reasons. Women have traditionally been the bedrock of the faithful, but a study last year by the Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate (CARA) of Catholic women showed that they are less engaged than in the past.

Those numbers have not raised the loud warning bells in the Catholic Church that they should have, critics say.

“For the first time in history women are leaving at greater rates than men,” said Ms. Rose-Milavec. “That is a deep dive.”

Pope Francis has spoken often of a more-incisive presence for women in the church, and six women occupy senior roles in the five dozen departments that make up the Catholic Church’s governing body, the Holy See. Critics say he needs to do more.

In 2016, Francis appointed a commission to review the place that female deacons had in the early church, a move seen by some as possibly opening the way to female deacons in the modern era. But the commission has not made its finding public, and the cardinal who heads it made clear last June that advising the pope on modern-day female deacons had never been on its agenda

“Through his positive statements, Pope Francis has really raised women’s expectations about the changes that he plans in order to bring more women into leadership roles,” Petra Dankova, the advocacy director of Voices of Faith, replied in a written response to questions. “But concrete actions have followed slowly and without an overarching plan.”

Voice of Faith, based in Liechtenstein, is pushing for women to gain full leadership roles in the Catholic Church. It has urged the close-knit group of cardinals who advise the pope on various issues that it should establish a special advisory board for women, Ms. Dankova said.

The question of their involvement in the church, she added, “is too complex and it cannot be expected to be somehow solved on the side without a concentrated attention and without the collaboration with women themselves.”

That suggestion has fallen on deaf ears, although some top prelates at the synod have been vocal in their support of women.

On Wednesday, speaking to reporters at a daily Vatican briefing, Cardinal Reinhard Marx, chairman of the German Bishop’s Conference, said that the issue of women’s roles in the church was “important for the entire church,” which must understand the evolution of women’s equality as a gift from God.

“We would be foolish not to make use of the potential of women,” Cardinal Marx said. “Thank God we are not that stupid.”

Male religious superiors at the synod have also been supportive, and the umbrella groups of both male and female superiors general have drafted a concrete proposal to allow women superiors to participate as voting members in future synods. If ratified by their respective boards, the proposal would be presented to the pope, Sister Hodgdon said.

After living in Rome for eight years, Sister Hodgdon, an American, said she has learned that the ways of the Church took time. Female superior generals were not likely to get the right to vote in this synod, she conceded. “But do I believe it will happen for the next one? Yes, I really do believe that.”

The next synod is scheduled for October 2019, and will focus on issues related to the Amazon region.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!