— An unprecedented global consultation of the faithful is galvanising rival liberals and conservatives

By Tony Barber

The American priest and author Andrew Greeley once said: “The opposite of Catholic is not Protestant. The opposite of Catholic is sectarian.” But just as secular politics in western countries is a battleground between mutually suspicious conservatives and liberals, so Greeley’s appeal to respect differences of religious opinion is drowning in a doctrinal struggle for control of the Roman Catholic Church.

The contest is all the sharper because Pope Francis turns 86 next month. Even if he does not emulate his predecessor Benedict XVI, who abdicated in 2013, the question of who will replace him looms large.

Papal infallibility, a doctrine proclaimed in 1870, is not rigorously applied these days, but the pontiff’s views carry unique authority. Disputes in Francis’s reign over women’s ordination, the Church’s treatment of divorcees, use of the Latin mass, sex abuse scandals and financial irregularities at the Vatican are therefore conducted with one eye on the cardinals’ conclave that will at some future date select the next pope.

Francis is no darling of progressive Catholics, for whom his approach to issues such as women’s role in the Church and homosexuality is too cautious. Still, conservatives correctly regard him as more reformist than Benedict or John Paul II, whose 1978-2005 pontificate made him the second-longest serving pope in the Church’s more than 2,000-year history. A case in point is Francis’s clampdown on the old Latin mass, which reversed Benedict’s decision to permit the celebration of some sacraments according to ancient rites.

Throughout his reign, however, Francis has emphasised healing the Church’s divisions as much as modernising its outlook and practices. In this spirit, he last year launched a global consultation of the faithful — an attempt to gauge the mood of the world’s Catholics, estimated by the Vatican at more than 1.3bn people, and chart a path for the Church’s future. He may have unleashed more than he bargained for.

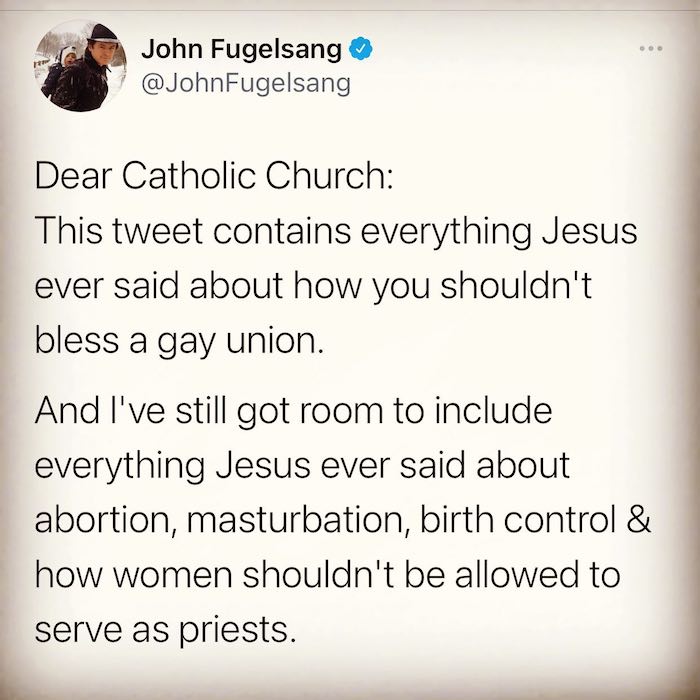

From dioceses across the world a torrent of reports has poured in. Many call for reforms, blocked since the 1962-1965 Second Vatican Council, to allow married clergy, women priests and acceptance of artificial birth control. A Vatican document last month observed: “Almost all reports raise the issue of full and equal participation of women.” On the other hand, conservative regions of the world — usually outside Europe and North America — are urging the Vatican not to yield to liberal pressure.

Francis’s consultation goes by the unwieldy name of the “synod on synodality”, implying inclusive discussion of pressing issues, though certainly not binding democratic votes. Yet the synod represents uncharted waters for the Vatican — and there is a cautionary historical parallel for Francis’s initiative. It is to be found in France on the eve of the 1789 revolution.

With the monarchy in crisis, Louis XVI summoned the Estates General — the future national assembly — to break the deadlock on reform. All across France, constituencies submitted so-called cahiers de doléance, or lists of grievances, as Catholic dioceses have done over the past year. A sort of nationwide opinion survey, the process prompted delegates meeting in Versailles to conclude that there was a public mood in favour of representative institutions, individual liberty, equality under the law and an end to absolutism. In the second half of 1789, the tide of revolutionary change became unstoppable.

It is premature to expect anything so world-shaking in the Catholic Church, where opinion appears more equally balanced between shades of radical reformism, moderate liberalism, mild conservatism and reaction. To take one example, the US consultation revealed deep splits on LGBTQ inclusion, clerical sexual abuse and the liturgy. “Participants felt this division as a profound sense of pain and anxiety,” the US bishops’ conference reported in September.

However, the central point is that both liberals and conservatives are discovering the force of public opinion. Cardinals, bishops and lay pressure groups frame their arguments for or against change in theological language but, as in France in 1789, notables and activists are seizing on the mood of society to advance and legitimize their causes.

The synod was supposed to end next year, but Francis recently extended it until October 2024. By then, either he will still be pope or an as yet unknown successor will be wearing his mitre. Either way, the struggle over the Church’s direction that has rumbled on since the Second Vatican Council and is being amplified by his synod may well be fiercer than ever.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!