By DIARMAID MACCULLOCH

The Catholic Church, aka the western church of the Latin rite, trades on tradition. That is what so fascinates many people: the lure of its continuity, the certainty, the serene provision of answers.

As anyone mildly acquainted with its history will know, this is a series of illusions. Christian history, like all history, is a delicious Smorgasbord of unintended consequences, paradoxes, misunderstandings, sudden veerings in new directions.

As anyone mildly acquainted with its history will know, this is a series of illusions. Christian history, like all history, is a delicious Smorgasbord of unintended consequences, paradoxes, misunderstandings, sudden veerings in new directions.

If you like to call that the work of the Holy Spirit, then fine, but do note that the Holy Spirit delights in confounding human expectations and going its own way.

The church of Rome, having been around from near the start of the story, illustrates this general truth particularly well. Its prestige derives from possessing the tomb of the Apostle Peter, who probably never visited the city.

This Palestinian fisherman, who would have spoken a version of Aramaic, plus enough street-Greek to make himself understood in the forum, may have been illiterate in either language, but he is represented among the books of the Bible by two elegantly-penned Greek letters written by two different authors – he himself was neither of them.

The current position of the Roman Catholic Church as the largest section of world Christianity depends on a variety of later accidents. One of these – the French Revolution of 1789 – produced the modern papacy. Until then, the pope was one Italian prince among several others.

Certainly he was equipped with a dozen centuries and more of ideological baggage, bulging with his aspirations to be something universal.

But he shared his power in the church inescapably with European Catholic monarchs, prince-bishops of the Holy Roman Empire and a host of other fiercely independent local jurisdictions in cathedrals and the like, all of which were themselves the products of the happenstance of history.

The revolution dealt them a devastating blow. As its consequences unfolded, it swept nearly all away, and the first World War delivered the coup de grace.

To begin with, it looked as if the revolutionaries would do for the pope as well. Poor Pius VI died in a revolutionary prison in France, his death in 1799 being recorded by the local mayor (with chilling Jacobin wit) as that of “Jean Ange Braschi, exercising the profession of pontiff”. But the papacy drew on its historical resources and on revulsion in much of Europe against revolutionary brutality and destructiveness.

It very successfully played the tradition card to create something brand new: a monarchy for the whole western church, which increasingly eliminated competition from rival jurisdictions. The 19th century revival of Catholicism laid the foundations of the rock-star papacy of John Paul II, kissing airport tarmac and thrilling crowds with the force of his exceptional personality.

While popular participation in secular politics has grown throughout Europe and America over two centuries, precisely the reverse has happened in the church of Rome: it has eliminated any wider participation, even that of kings.

The post-revolutionary Vatican remodelled the church across the world, to eliminate independence in church government, local initiative or scholarship.

In Ireland, the process took up the later 19th century, to produce the variety of Catholic Church still easily within the memories of many, embodied by such prelates as the late and widely unlamented John Charles McQuaid.

The reforming work of the second Vatican Council (1962-1965) looked for a moment as if it would roll back this 19th-century innovation, but the curia’s bureaucrats in the Vatican were left to implement council initiatives, and we all know the results of that in the two pontificates of John Paul II and Benedict XVI.

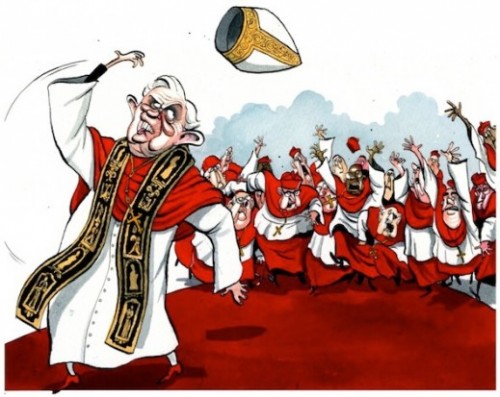

Benedict, arch-traditionalist, expounding even this week a narrative of Vatican II in which nothing much happened at all to the church, has by his resignation set the church on yet another new path.

It is paradoxical but admirable that this sensitive and learned man has recognised the limits of his office. The all-powerful, all-providing papacy constructed after 1789 has simply been too much for any one man to embody, regardless of whether he is frail or old.

The cardinals whom John Paul and Benedict appointed to parrot the myth of enduring tradition will no doubt resist the implications, scrabbling around to find the most convincing representative of the post-French Revolution state of the hierarchy. But it is just possible that the Holy Spirit might seize them afresh.

Wouldn’t it be a wonderful surprise for the Christian world if they reached beyond the conclave and chose someone from beyond their ranks? That’s a big ask at the moment. But look back before the French Revolution, and we can find stories to help the church in framing a more workable version of its future than the present dysfunctional structure.

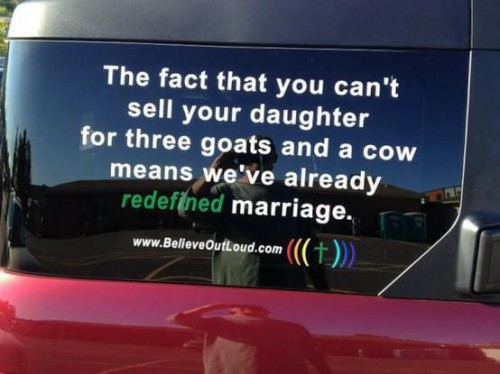

At the moment, the debate between Catholic “liberals” and “conservatives” is stuck around the second Vatican Council: what happened there? Not much? A lot? Even more than a lot, but frustrated by the Curia? Let’s recognise that the debate is much older than that.

A great many Catholics over the centuries have considered a monarchical papacy a very bad idea: particularly all those monarchs, prince-bishops, cathedral chapters. They constructed coherent theologies out of their convictions.

Historians use labels for these ways of thinking which have become merely pieces of historical jargon: Gallicanism; Cisalpinism; Conciliarism.

It’s a pity that these words now seem off-putting and archaic, because once they were living affirmations that the church’s future should be decided in broader arenas than a few chambers in the Vatican palace.

That future won’t resemble the past – it never does – so I’m not suggesting we restore the Holy Roman Empire, or the heirs of Louis XVI to the French throne. But history has rich resources to offer: showing how they did things in the past, so Catholics can find sensible solutions for what to do next.

In the middle of what any fool can see is a deep crisis in Catholic Church authority, let historians ride to the rescue.

Complete Article HERE!