Editor’s Note: Last autumn, Alexis Record and Tom Rastrelli appeared together in one of many blog posts here that commemorated The Clergy Project’s 1000 Member Milestone. I thought they were a good example of the variety of religious backgrounds that people who leave religion come from. Now they are back together in what I think is even a more interesting way – a former fundamentalist reviewing the memoir of a former Catholic priest. /Linda LaScola, Editor

First, with permission from the publisher, Alexis starts with excerpts from the prologue:

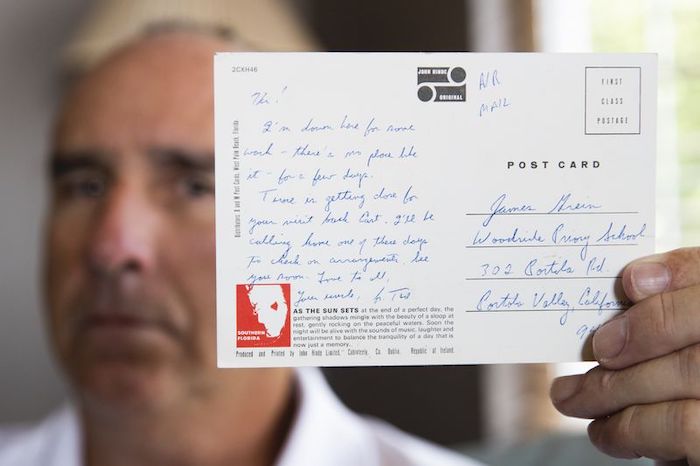

The Church needed something new. In January, the Boston Globe had exposed Cardinal Bernard Francis Law for covering up the sexual abuse of minors by priests. As the months before my ordination passed, a mounting number of bishops fell in shame. I doubted my calling. But the Church was different in Dubuque. My archbishop hadn’t harbored pedophiles. He’d turned them over to the police. He’d offered their victims support and healing. I would do the same.

After the archbishop completed the prayer, a priest lifted the deacon’s stole from my shoulder and replaced it with a priest’s stole. Over my head, he lowered a chasuble with gold-and-blue embroidery matching the archbishop’s. I crossed from the center of the sanctuary to the cathedra, the ornately carved oak throne where the archbishop sat. I knelt before him. From a crystal pitcher, he poured syrupy chrism–holy oil scented with balsam–over my upturned hands. Pressing his palms against mine, the archbishop smeared large crosses as he prayed: “The Father anointed Our Lord Jesus Christ through the power of the Holy Spirit. May Jesus preserve you to sanctify the Christian people and to offer sacrifice to God.” He folded his glistening hands around mine. His dark eyes were absolution. I would sacrifice myself for him, for God.

Hands dripping with chrism, I stood, turned, and walked to my spot at the foot of the altar. I glanced at the front row into my parents’ eyes. They were crying, grinning. I smiled through tears. I was a priest.

[—]

Less than two years later, I turned my back on the archbishop. This time, I held my tears. I rushed from his office into February’s darkness. The frigid night air burned my cheeks. In the corner of the icy parking lot, my black pickup offered refuge. My only private space, it was where I retreated to sing, talk on my phone, and cry–all the things a young priest didn’t want his pastor or cleaning lady to witness. I drove through blocks of Catholic neighborhoods, people who trusted the archbishop. Now, I had to obey his command by covering up sexual abuse.

[…]

On the north end of town, a boat ramp would provide easy access to the frozen Mississippi. My plan: drive until the ice buckled under the weight of the truck.

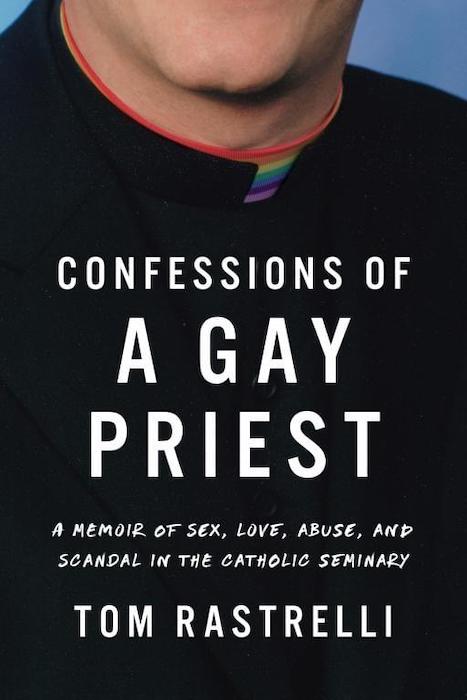

Tom Rastrelli

Confessions of a Gay Priest: A Memoir of Sex, Love, Abuse, and Scandal in the Catholic Seminary

By Alexis Record

For half a decade now I have been a Free Hugs Mom at our local Pride parade with Sunday Assembly San Diego. I become everyone’s mom despite age differences and embrace hundreds of people while making sure they’re drinking water and wearing sunscreen in the summer sun, you know, Mom concerns. Most importantly of all, I tell folks I’m proud of them. Most laugh or smile at my apron, some cry, and a few collapse into my arms as if a stranger’s acceptance might squeeze their fractured parts into some semblance of wholeness. As our group discussed doing an emotionally exhausting two-day Pride event this year, I was still recovering from finishing my tear-stained advanced copy of Tom Rastrelli’s book, Confessions of a Gay Priest: A Memoir of Sex, Love, Abuse, and Scandal in the Catholic Seminary. It solidified my resolve to love on those kids.

Recently it felt as if an additional child was in my home: young Tom Rastrelli. I poured my love and support into him as he navigated pure hell. “Oh baby,” I’d tell him as he doubled down on homophobic lessons and planted deeper roots into his own victimization, like a vulnerable plant choosing the darkest corner where growth was promised.

What makes Rastrelli’s story so compelling are his flourishes of detail. His experiences are incredibly visceral–a real strength of his writing–which in turn make the abuses he suffered that much more excruciating. Each page is pure beauty and heartbreak. I found myself unable to put it down, needing to know what happens next. Needing to know Tom would be okay.

Rastrelli excavates the darker parts of his theology and clerical experiences without being anti-Catholic. In fact, I was struck with the humanity of his fellow seminarians and priests. The religious boy’s club included drinking, swearing, smoking, sexism, and jokes about pedophilia as the topic of the day which would not look out of place among a group of men in any other part of society. These boys grow through spiritual practice into priests. They are portrayed with a fair hand, not as monsters, but as loving servants of congregants who become unwitting facilitators of abusive and inhumane doctrines. They encouraged counseling, but not from women who pointed out sexism within the system. They practiced forgiveness, but used it to sweep grievous abuses under the rug. They offered real friendship, but caused their friends to hate their sexualities. They were real people, good people, doing the best they could with the tools they had. It made me want to take my local priest out to coffee to see how he’s holding up.

I’ve never been Catholic. The closest I’ve come is years ago working as a priest’s sign language interpreter during Mass. I outed myself as protestant by signing each word of “Father, Son, and Holy Spirit” instead of crossing myself and as a result wasn’t asked back. Yet, I did not need to be completely familiar with all aspects of Catholic tradition to follow this story. Any conservative Christian will recognize, as I did, the strong desire to be lost in God’s presence, the pressure to cover up for the sins of godly men, and the deep self loathing after every masturbatory orgasm.

Rastrelli takes the reader on a unique journey most of the faithful never see. Like many of the other wide-eyed liberal students who loved the Church, he set out to affect change from within it only to be gradually and incessantly chiseled into the very shape of those hard beliefs he did not think reflected Christ. Seminarians during this process swallowed larger and larger boluses of cognitive dissonance until they were either consumed from within or vomited out of God’s presence. They were told not to make waves and not to confuse the faithful with their own doubts about the system. It was amazing to me just how so many good people became unwilling participants in facilitating horrific evils. Offering a holy profession for homosexual men who would never be allowed to have sex within the confines of that system and then laying all the blame for child predation upon the gays is just one of those evils.

The brutal parts of this story include the author’s homophobia recounted from his early years and directed selfward like a knife at his own throat, the sexual abuse the reader voyeuristically shares, and, almost worse, the excusing and minimizing of that abuse by the very men supposedly speaking and acting for God himself. Worshipping a tortured savior meant suffering throughout the story was almost always mistaken for love. Oh baby.

Silent no longer, Tom Rastrelli bravely reopens wounds and lays bare scars for all to see. His memoir is a breathtaking, priceless treasure–a bright light in the darkness. I’m proud to recommend it to believers and unbelievers alike. For victims of abuse, I suggest being gentle with yourself while reading. Also, drink some water, wear your sunblock, and avoid hazardous religious systems.

Confessions will be available April, 2020. Preorders available now, from Amazon.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!