Woman’s suit against Lutheran youth pastor is first in an effort to get more to step forward.

A national team of lawyers has joined forces to focus on a group of children who are underrepresented in clergy abuse cases — namely, girls.

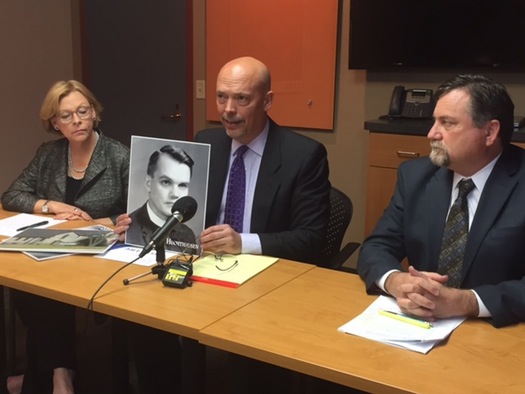

The group announced its first legal action Monday, a suit by a Minnesota woman who charges that she was sexually abused for several years in the 1970s by a former youth minister at Zion Lutheran Church in Hopkins.

Although 1 in 4 girls reports being a victim of child sex abuse in national studies, just a small fraction of them take advantage of laws that permit victims to seek legal remedy in decades-old cases, Patrick Noaker, a Minneapolis attorney who is part of the team, said at a news conference.

The relatively small number of women stepping forward is true not just for clergy sex abuse, said fellow team member Marci Hamilton. In general, girls are reluctant to report abuse by coaches, teachers, family members and family friends, Hamilton said. Yet all can be sued through the Minnesota Child Victims Act, which allows older abuse cases to have their day in court.

Similar laws are on the books in Hawaii, Georgia, Massachusetts and Connecticut, she said.

Fifteen other states considered passing similar laws last year, she said, and many are likely to do so again next year.

“Survivors see who is coming forward and are mobilized by who is coming forward,” said Hamilton, a law professor at Cardoza School of Law in New York and a national authority on clergy abuse litigation.

“We have an epidemic of child sex abuse,” she said. “I hope that women across the country will find their voices, so that the public will learn who are the hidden predators.”

The goal of the legal team is to make sure that women are aware that they can take their perpetrators to court — even if those perpetrators were not priests or ministers and even if it was decades past, Noaker said.

“The [Child Victims Act] was passed for everyone sexually abused in Minnesota, not just altar boys,” said Noaker.

Monday’s lawsuit was filed on behalf of a 52-year-old woman who says she was abused by the Rev. John Huchthausen, Zion Lutheran’s youth minister, beginning in 1974 when she was 12 years old. The girl was a member of the church.

He is now deceased.

The sexual abuse happened at and around the church, on youth retreats, and in other settings, the lawsuit charges. It says the church had knowledge of Huchthausen’s behavior, “but failed to act on the knowledge.”

Zion Lutheran Church declined to comment on the charges, filed in Hennepin County District Court.

The team handling the case includes Noaker, Hamilton, and Idaho-based attorneys Leander James and his law partner, Craig Vernon. Noaker has been representing child abuse and clergy abuse cases across the country since 2002. So has James, who has represented victims of the Diocese of Montana and the Jesuit Order in Oregon, among others.

The three attorneys will file the claims, lead the discovery of evidence and represent victims at trial, said Noaker.

Hamilton, a legal scholar on church-state issues, is a widely recognized national appellate lawyer. A child protection advocate, she has argued before the U.S. Supreme Court as well as consulted with state legislatures on the most effective child-protection laws.

Hamilton will handle legal challenges to the cases and appeals, Noaker said.

“It’s almost like we’re creating a larger firm,” said Noaker. “We almost have to. Whether it be a [Catholic] diocese or Lutherans or the Boy Scouts of America, they will engage a large number of lawyers to fight at every turn. We have to match that. That’s what we are doing here.”

Beyond priests and ministers, athletic coaches are a likely priority target of the group.

“Elite athletes tend to be most at risk,” said Hamilton. “They spend more time with their coaches, who have access to scholarships … and they spend a lot of time away from their families.”

The legal team is likely to take legal action on such a case early next year, she said.

Complete Article HERE!