A dozen people crammed into a parish hall Wednesday night to earn a certificate in “Protecting God’s Children.”

The two-hour course has been provided by the Roman Catholic Diocese of Kansas City-St. Joseph for the past decade and was designed to help people detect warning signs of child sex abuse and know how to report inappropriate behavior.

But the obvious subtext of the event — splashed across headlines nationwide this month — remained, for the most part, unspoken. Apart from a passing reference to “the news,” those who participated in the training heard nothing of the indictment this month of their diocese and current bishop, Robert Finn, for failing to report child abuse.

Catholic school teachers attended the training at St. George Parish in Odessa, Mo., along with a maintenance man, women planning to chaperone a bus trip to a youth convention and somebody who occasionally tends a church snack booth.

The course leader cautioned the group that the grainy videos they were about to see would be troubling; anyone could step into the hall if needed. Footage included stories from victims and perpetrators who described how they repeatedly groomed children for years, often near unwitting adults.

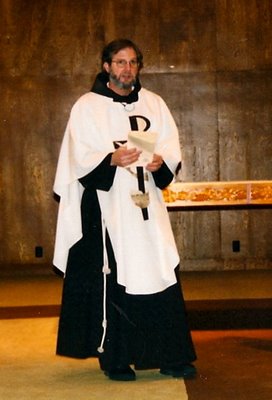

“Despite our best efforts, there is one nightmare that no child should have to experience,” former acting bishop of the diocese Raymond Boland said in the videos about child sex abuse. He added that the problem has been hidden for years and the “hesitance to report” is a tragedy that “protects people who shouldn’t be in positions of trust.”

Boland encouraged parents to have “healthy suspicion.”

“You go with your gut,” course leader Katherine Brown told the group. “If something is a little off, something is a little off.”

Kelly Blankenship said she thought about the diocesan turmoil throughout the class. She’d read the 141-page report posted on the diocese website that laid out the case of the Rev. Shawn Ratigan. Ratigan faces state and federal child pornography charges, not to mention civil claims against him and the diocese that allege Ratigan was protected instead of children.

Finn himself has apologized that the diocese was slow to react. But the glaring warning signs seemed to jump right out of the videos in the child safety class.

“It’s almost like a joke,” said Blankenship, 33, a mother of three.

Clergy sex abuse cases have made national headlines for a decade. Church leaders have promised reforms and formed internal review boards. The church has paid about $2 billion in civil claims.

Recent indictments of clergy in Philadelphia and Kansas City signal there is still work to be done, said Terry McKiernan, president of Bishopaccountability.org, an online library of abuse cases.

“If it’s not working in Philadelphia or Kansas City then there is a concern that it’s not working elsewhere, too, because the system is the same everywhere in the U.S.,” he said.

But experts also say the indictments against the Kansas City diocese and high-level authorities like Finn and Monsignor William Lynn of Philadelphia, who was charged in February with child endangerment, ushered in a new phase of housecleaning: The threat of criminal consequences for managers who fail or are slow to report abuse.

“If they don’t learn their lesson this time, I can’t imagine what the next phase would be (other than) the continual eroding in the confidence of clergy,” said Dennis Coday, managing editor at the National Catholic Reporter, an independent publication based in Kansas City.

‘CONTRIBUTE SOMETHING’

Many are baffled by the indictments announced Oct. 14 because in 2008, the Diocese of Kansas City-St. Joseph paid $10 million to settle abuse claims with 47 victims. Finn apologized then for the “fully unacceptable behavior” that prompted the lawsuits and assured that new measures were in place “so that we may be confident there will never, ever be a repeat of the behaviors.”

Blankenship and many others are sticking by their faith while hoping future red flags will be handled swiftly and in the open.

“If we can contribute something positive, then our faith can outlive these kinds of tragedies,” she said.

For her that means teaching Sunday school at nearby St. Jude the Apostle Mission in Oak Grove, Mo.

More vocal Catholics say Finn has lost his moral authority and needs to step down. The Facebook page “Bishop Finn Must Go” is gaining hits.

Some of the hostility against Finn predates the latest crisis. Ever since Finn arrived from St. Louis in 2005, he has been trying to navigate the Kansas City diocese away from its progressive roots and toward adherence to traditional church rules.

Meanwhile, others believe Finn, who pleaded not guilty to the misdemeanor charges, has been the target of zealous advocacy groups and prosecutors. At worst, a veteran priest said, Finn has fallen prey to his two main qualities — kindness and trust.

“He’s a kind man in the way of taking a person, regardless of their failure or sin, and trying to bring them back to Christ,” said Monsignor William Blacet, 89. “He’s a very trusting soul. Those two things have gotten him in trouble.”

In a letter to the Kansas City Star, Frank Kessler, emeritus professor of government at Missouri Western State University in St. Joseph, asked for the charges to be dropped.

“There are those who want to paint Finn as a poster boy for the clerical abuse scandals,” he said. “That just does not pass the smell test.”

RED FLAGS

A year after Finn’s apology, Ratigan showed up at St. Patrick Parish in North Kansas City and its nearby school and day care. He was bald, wore a leather jacket and drove a Harley-Davidson motorcycle. He loved to interact with children, and parents adored him for it.

Ratigan also had a passion for photography and often carried a camera.

But soon parents and teachers started noticing “boundary violations,” according to an investigative report of his case commissioned and publicized by the diocese. His Facebook page had pictures of children sitting on his lap and a photograph of him swimming in a lake with young girl.

On May 19, 2010, Principal Julie Hess wrote a complaint about his behavior and shared it with Vicar General Monsignor Robert Murphy, the bishop’s right-hand man. According to the report, a parent was alarmed to have seen Ratigan rubbing his daughter’s back. His home seemed “tailor made for children,” with stuffed animals, a large fish tank and a kitchen “adorned with towels shaped like doll clothes.” A pair of young girl’s panties was found in a backyard planter.

Hess said she didn’t call the Missouri Division of Family Services hotline because she didn’t suspect abuse.

In December, after Ratigan reported problems with his laptop, a technician discovered “hundreds” of images of young girls on his computer, including pictures of their crotches and at least one image that showed the exposed genitals of a little girl, according to court records.

The computer was turned over to the diocese and the next day Ratigan tried to kill himself in his garage.

Murphy, the vicar general, consulted a police captain on the diocese’s internal review board, but only described one image and didn’t tell him there were many, according to the diocesan report. No other police, parish leaders or parents were notified.

Ratigan recovered and was pulled from St. Patrick to minister at a convent. Finn gave him a set of restrictions, but Ratigan only “grew bolder” by accessing computers and having continued contact with children, according to the report.

Five months after the images were found, Murphy reported Ratigan to police.

Soon after, the diocese hired former U.S. Attorney Todd Graves to investigate. His report concluded that the organization’s abuse policy must “encourage all employees to contact police” and that “the second most serious failing” was Murphy’s and the “apparent acquiescence by Bishop Finn not to report the laptop incident.”

Finn again apologized, promising new reforms that assured any future allegations of abuse would be handled by an ombudsman, currently a former prosecutor.

“From our perspective the apologies are utterly meaningless, because who doesn’t apologize when they are caught red-handed,” said David Clohessy of SNAP, a victim’s advocacy group. “Any sincere apology is accompanied by real change and that isn’t happening in Kansas City.”

But Finn’s latest public apology softened Sally Radmacher. As recently as August she had picketed in front of the downtown Kansas City cathedral over the handling of the Ratigan case.

“Certainly as Catholics we are called to forgive,” she said.

A spokeswoman for the diocese declined to comment and forwarded questions to Gerald Handley, an attorney representing Finn.

“He’s sorry for how he handled it after the fact, after the mismanagement issues — not with respect to his criminal responsibility,” Handley said. “They are two different issues.”

Finn continued last week in his roll as bishop. He celebrated Mass, heard confessions and stopped by a fundraiser. He and other priests in the diocese attended a retreat at Lake of the Ozarks.

STILL UNSETTLED

Fifteen members of Ratigan’s former flock gathered for Mass last week in a small chapel at St. Patrick.

Janet Morris, a lay minister, led the service. She told the group: “Our goal is peace in our hearts, and yet we are very far from that.” She asked them to pray for their leaders who are “striving to bring gospel values into our daily lives.”

But after the service she and others described how they are still unsettled by Ratigan’s case.

“To me it’s like a kid trying to blame someone else,” she said. “Anybody should know to call the police.”

Next door, Julie Hess, the principal who initially reported Ratigan in May 2010, said in an interview that she initially thought he didn’t know the boundaries for working with children.

She said she offered Ratigan a binder of training materials but he declined, saying he was aware of the rules. She stands by how she handled it without knowing about the photographs.

“You don’t call the police to say this guy is creepy,” she said. “We had no reason to suspect abuse.”

Hess and others at St. Patrick are ready for the emotions surrounding the case to clear. Not that it will be forgotten. It’s embarrassing.

Just outside the school office last week, Maia Hamilton, 33, lugged a child seat as a child tugged on her other arm, wanting to be held. Hamilton said she “felt like a fool” when Ratigan’s case became public.

The mother of four said she was blindsided because Ratigan was personable and she liked him.

“You just don’t know what to look for anymore,” she said.

Complete Article HERE!