By CLAUDIA LAUER and MEGHAN HOYER

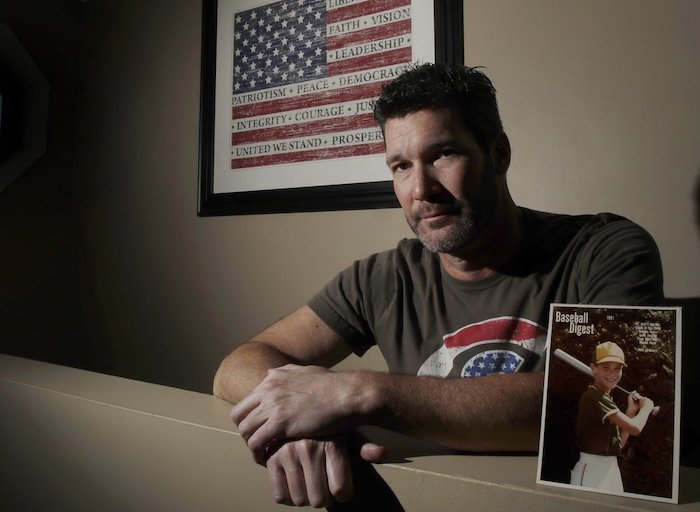

Richard J. Poster served time for possessing child pornography, violated his probation by having contact with children, admitted masturbating in the bushes near a church school and in 2005 was put on a sex offender registry. And yet the former Catholic priest was only just this month added to a list of clergy members credibly accused of child sexual abuse — after The Associated Press asked why he was not included.

Victims advocates had long criticized the Roman Catholic Church for not making public the names of credibly accused priests. Now, despite the dioceses’ release of nearly 5,300 names, most in the last two years, critics say the lists are far from complete.

An AP analysis found more than 900 clergy members accused of child sexual abuse who were missing from lists released by the dioceses and religious orders where they served.

The AP reached that number by matching those public diocesan lists against a database of accused priests tracked by the group BishopAccountability.org and then scouring bankruptcy documents, lawsuits, settlement information, grand jury reports and media accounts.

More than a hundred of the former clergy members not listed by dioceses or religious orders had been charged with sexual crimes, including rape, solicitation and receiving or viewing child pornography.

On top of that, the AP found another nearly 400 priests and clergy members who were accused of abuse while serving in dioceses that have not yet released any names.

“No one should think, ‘Oh, the bishops are releasing their lists, there’s nothing left to do,’” said Terence McKiernan, co-founder of BishopAccountability.org, who has been tracking the abuse crisis and cataloging accused priests for almost two decades, accumulating a database of thousands of priests.

“There are a lot of holes in these lists,” he said. “There’s still a lot to do to get to actual, true transparency.”

Church officials say that absent an admission of guilt, they have to weigh releasing a name against harming the reputation of priests who may have been falsely accused. By naming accused priests, they note, they also open themselves to lawsuits from those who maintain their innocence.

Earlier this month, former priest John Tormey sued the Providence, Rhode Island, diocese, saying his reputation was irreparably harmed by his inclusion on the diocese’s credibly accused list. After the list was made public, he said he was asked to retire by the community college where he had worked for over a decade.

Some dioceses have excluded entire classes of clergy members from their lists — priests in religious orders, deceased priests who had only one allegation against them, priests ordained in foreign countries and, sometimes, deacons or seminarians ousted before they were ordained.

Others, like Poster, were excluded because of technicalities.

Poster’s name was not included when the Davenport, Iowa, diocese issued its first list of two dozen credibly accused priests in 2008. The diocese said his crime of possessing more than 270 videos and images of child pornography on his work laptop was not originally a qualifying offense in the church’s landmark charter on child abuse because there wasn’t a direct victim.

After he was released from prison, the diocese found Poster a job as a maintenance man at its office, but he was fired less than a year later after admitting to masturbating in the bushes on the property, which abuts a Catholic high school. Still, the diocese did not list him.

Poster went on to violate the terms of his probation, admitting he had contact with minors at a bookstore and near an elementary school, federal court records unsealed at the AP’s request show. A judge sent him back to jail for two months and imposed several other monitoring conditions.

Child pornography was added to the church’s child abuse charter in 2011 and, though the diocese promised it would update its list of perpetrators as required under a court-approved bankruptcy plan, it never included Poster.

“It was an oversight,” diocese spokesman Deacon David Montgomery told the AP. He said the public had been kept informed about the case through press releases issued from Poster’s arrest until his removal from the priesthood in 2007.

Poster, now 54, lives in Silver Spring, Maryland, near a school and two parks. He hasn’t been accused of any wrongdoing for more than a decade and declined to comment when reached by the AP, saying he preferred to stay out of the spotlight.

Of the 900 unlisted accused clergy members, more than a tenth had been charged with a sex-related crime — a higher percentage than those named publicly by dioceses and orders, the AP found.

Dioceses varied widely in what they considered a credible accusation. Like Poster, some of the priests criminally charged with child pornography weren’t listed because some dioceses said a victim needed to report a complaint. In addition to Poster, the AP review found 15 other priests charged with possessing, distributing or creating child pornography who were not included on any list.

Other dioceses created exceptions for a host of other reasons, ranging from cases being deemed not credible by a board of lay church people to the clergy members in question having since died and thus being unable to defend themselves.

“If your goal is protecting kids and healing victims, your lists will be as broad and detailed as possible. If your goal is protecting your reputation and institution, it will be narrow and vague. And that’s the choice most bishops are making,” said David Clohessy, the former executive director of the Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests, who now heads the group’s St. Louis chapter.

The largest exceptions were made for the nearly 400 priests in religious orders who, while they serve in diocesan schools and parishes, don’t report to the bishops.

Richard J. McCormick, a Salesian priest who worked at parishes, schools and religious camps in dioceses in Florida, New York, Massachusetts, Indiana and Louisiana, has been accused of molesting or having inappropriate contact with children from three states. In 2009, his order settled the first three civil claims against him. Yet he does not appear on any list of credibly accused clergy members.

McCormick finally faced criminal charges after one of his victims spotted the priest’s name on a very different list — one posted in 2011 by a Boston lawyer, Mitchell Garabedian, who represents church sexual abuse victims.

Thirty years had gone by, but Joey Covino said he immediately recognized a photo of McCormick as the priest who had molested him over two summers at a Salesian camp, a woodsy retreat for underprivileged boys in Ipswich, Massachusetts. Covino’s boyhood had revolved around church, where he served as an altar boy, played in a Catholic Little League and where his mother — raising four children on her own — gratefully accepted assistance from friendly priests.

When she sent Covino and his brothers back to the free camp for a second year, “I was petrified — petrified — and I couldn’t say anything. I couldn’t even ask my brothers to see if it had happened to them,” said Covino, now 49 and a police officer in Revere, Massachusetts. “I’ve always told myself I should have done something. I should have fought back.”

Covino said the entirety of his adult life had been altered by McCormick’s abuse — failed relationships, his decisions to join the military and later the police, nightmares that plagued him. His decision to come forward led to McCormick being convicted of rape in 2014 and sentenced to up to 10 years. The priest since has pleaded guilty to assaulting another boy.

The Salesians, based in New Rochelle, New York, have never posted a list of credibly accused priests.

“Our men who have been credibly accused and have had accusations have been listed in the various dioceses that we serve,” said Father Steve Ryan, vice provincial of the order.

Ryan said he was certain McCormick’s name appeared on several lists, including Boston’s.

But when Boston posted its list in 2011, Archbishop Sean Patrick O’Malley wrote that he was not including priests from religious orders or visiting clerics because the diocese “does not determine the outcome in such cases; that is the responsibility of the priest’s order or diocese.”

O’Malley since has called on religious orders to post their own lists, spokesman Terry Donilon said.

The AP found the Boston archdiocese has the most accused priests left off its list, with almost 80 not included. Nearly three-quarters, like McCormick, were priests from religious orders. Another dozen died before allegations were received — another exclusion cited by the archdiocese.

McCormick also is not on the New York archdiocese’s list or lists posted by the Archdiocese of Gary, Indiana, and the Diocese of St. Petersburg, Florida — both places where he faced accusations.

After the AP inquired, a spokeswoman for the archdiocese in New Orleans, where McCormick served in 1991, said the archdiocese would seek to verify information about the priest and add him to its list.

If McCormick goes onto New Orleans’ list, he would be excluded from the AP’s undercount analysis, despite still being absent on lists in the other dioceses where he served. Because the AP counted only priests left off all lists, critics say the number of 900 unnamed priests represents just a tiny portion of the true scope of the underreporting problem.

Other priests excluded from the credibly accused lists were left off because of findings from the diocesan investigations process.

Review boards — independent panels in each diocese staffed with lay people to review allegations of abuse — make the initial recommendation on whether an allegation is credible. The standards those boards use to investigate claims and the process itself often is so shrouded from public view that some victims say they weren’t allowed to attend when their allegations were discussed.

Dozens of priests whose accusers received payouts or legal settlements were left off credibly accused lists because review boards deemed the accusations not substantiated or because bishops or even the Vatican later overturned the board’s findings on appeal. The standards for Vatican appeals are even more secretive.

In 2006, the Chicago Archdiocese’s review board investigated a claim from two brothers who alleged a priest named Robert Stepek had abused them. The board found “reasonable cause to suspect that sexual abuse of minors occurred,” but Stepek was restored to good standing in 2013 after a Vatican court said it was “unable to find evidence strong enough.” The court found Stepek engaged in inappropriate behavior for a priest, however, and he remained without an assignment under restrictions until his death in 2016.

The AP found about 45 accused clergy members who did not appear on the Archdiocese of Philadelphia’s list of credibly accused priests. The archdiocese said they were excluded for a variety of reasons, including deciding that about a dozen priests found unsuitable for ministry by a review board due to conduct involving minors did not do anything that rose to the level of abuse.

A spokesman said the archdiocese has a thorough and transparent investigation process, but declined to comment on any of the individual cases of priests not named on its list.

Pennsylvania Attorney General Josh Shapiro told the AP that he had to fight church leaders to release a groundbreaking 2018 grand jury report that named more than 300 predator priests and cataloged clergy abuse over seven decades in six of the state’s dioceses, not including Philadelphia.

Several bishops played a direct role in covering up the abuse in Pennsylvania, Shapiro said.

“You can’t put much stock in the lists that the church voluntarily provides because they cannot be trusted to police themselves,” he said.

In Buffalo, New York, Bishop Richard Malone resigned under pressure earlier this month after his executive assistant leaked internal church documents to a reporter after becoming concerned the bishop had intentionally omitted dozens of names from its list of credibly accused priests.

Buffalo’s list has more than doubled to 105 clergy members since those documents were released. Still, the AP found nearly three dozen accused priests who remain unnamed by the diocese.

The number of new claims being reported to law enforcement and church officials over the last two years has increased, spurred in part by revelations of abuse from high-ranking church officials such as former Cardinal Theodore McCarrick and by the Pennsylvania grand jury report and the more than 20 other state investigations launched in its wake.

The AP found more than 130 priests who were accused in the last two years whose names do not appear on any lists. Another 37 unlisted priests were accused under New York’s Child Victims Act, which recently opened a window for victims to file civil lawsuits regardless of the statute of limitations, a trend being echoed across the country.

Anne Burke, now chief justice of the Illinois Supreme Court, was part of the Catholic Church’s inaugural National Review Board, a commission formed to help implement the church’s 2002 child abuse charter.

“We gave our report and recommendations over 15 years ago. They never followed through. That was the final nail in the coffin as far as we were concerned in terms of the bishops ever being able to pull themselves away … from the bureaucracy and be transparent,” Burke said. “That is why we are here again today, and it’s worse.”

Many advocates say the church has a long way to go toward being transparent and are determined to see that it becomes far more open about problem priests.

Attorney Jeff Anderson, known for suing dioceses for information on accused clergy, has released almost 30 various rosters of clergy he has received allegations against or whose names appear in church documents.

“We feel a fierce public imperative to continue to release our lists because those released by dioceses contain only a fraction of the true report,” Anderson said. “And they lead people to believe they are coming clean when they are not.”

It was a list that Anderson’s law firm released in the Archdiocese of New York that led 34-year-old Joe Caramanno to file a complaint, decades after he said he was abused.

Caramanno had been hospitalized for an anxiety disorder when he was a teenager and part of his return to high school involved mandated meetings with a priest who controlled his medication. It was during those sessions that Caramanno said Monsignor John Paddack fondled him.

Caramanno, now a teacher, said it wasn’t until he saw Paddack’s name on Anderson’s list that he felt he could come forward. “I needed the validation that it wasn’t just me. It made it more real,” he said.

The archdiocese’s official list of credibly accused priests, released a few months after Anderson’s, contains only half the names and does not include Paddack, who has stepped down during the ongoing investigation.

“It makes me wonder if I hadn’t come forward … would he still be an active priest?” said Caramanno, who has filed a lawsuit against the archdiocese under New York’s Child Victims Act.

An archdiocese spokesman said a request for comment had been relayed to Paddack, but the priest did not respond.

Victims and advocates say the church should be transparent about investigations when allegations are received, arguing that trust in the church can be restored only if bishops are completely forthcoming.

Several dioceses have chosen to include priests under investigation on their lists, removing them if the allegations are determined to be unsubstantiated, but many others do not disclose investigations or include those names.

“Every cleric no matter where they came from or were ordained or went to school or who signs their paycheck … all of that is hair-splitting and irrelevant,” said Clohessy, of the group SNAP. “What matters is one question: Did or does this credibly accused predator have access to my flock ever? Even for a few hours. If the answer is yes, then that bishop needs to put that predator on his list.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!