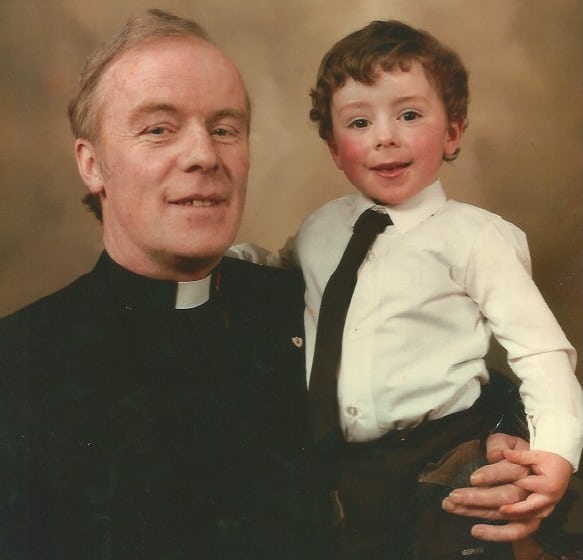

On Dec. 17, the Rev. Gregory Greiten shared a secret with parishioners at the St. Bernadette Catholic Parish: “I am gay.” Greiten was then greeted with a standing ovation, according to the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel.

The next day, Greiten wrote a column in the National Catholic Reporter. As someone who now uses the descriptor “recovering Catholic” to answer questions about my religious identity, was once approached for the priesthood, struggled with reconciling my faith with my sexual orientation, and just finished writing about these experiences and more in a book called I Can’t Date Jesus, much of what Greiten wrote felt all too familiar.

“Each time I had a great desire to speak out I was challenged by other priests and leaders,” he wrote before breaking down the various responses—all of which can be tied under the bow of the sentiment “Keep your sins to yourself.” The advocacy for his continued silence was centered on the belief that to come out as gay would result in damages to his ministry at least, and expulsion from the church at worst. While it might have been wrong to call upon Greiten to deny who he is in a space where people go to seek answers about God and themselves, their fears were aided by precedent.

The New York Times’ Christine Hauser noted:

The Rev. Warren Hall was fired from Seton Hall University’s ministry in 2015 after he came out as gay. In 2004, the Rev. Frederick Daley, now a pastor at All Saints Parish in Syracuse, came out, angered by what he called the “scapegoating” of gay priests during the church sexual abuse scandal.

Father James Martin, a Jesuit priest who has written a book called “Building a Bridge,” about L.G.B.T. Catholics, said that between 20 percent and 30 percent of Catholic priests are celibate gay men and that a larger reason they have not been public about their sexuality is homophobia in the church.

It is no wonder that Greiten laments about the “heavy burden” he carried with him. I know that burden, despite not being a member of the clergy. If you find yourself the child, brother, son or friend of a religious person with rigid ideas of what’s right and wrong, then you, too, will find yourself told to be silent, purportedly for the sake of your own good.

Like Greiten, I was taught that homosexuality was something “disordered, unspeakable and something to be punished.” I thought I was going to go to hell for every thought I had, every touch I contemplated, each time I gave in to temptation. It’s a haunting, shameful feeling that eats you inside. You become so accustomed to guilt that even if you dare to be truthful about who you are in all settings, you may still find yourself having to learn to shake off old habits, like guilt. Religions in general tend to make their believers feel guilty about their misdeeds, but Catholics are particularly adept when it comes to guilt.

That’s why it matters so much that Greiten has stepped forward and gained national attention. There are many more like him. Just how many is unclear, but none of them should feel compelled to linger in the shadows.

Greiten explains the necessity for more visible gay priests to step forward:

There is no question there are and always have been celibate, gay priests and chaste members of religious communities. According to the Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate, in 2016, there were 37,192 diocesan and religious priests serving in the United States. While there are no exact statistics on the number of gay Catholic priests, Fr. Donald B. Cozzens suggested in his book, The Changing Face of the Priesthood, that an estimated 23 percent to 58 percent of priests were in fact gay. It would mean that there are anywhere from 8,554 (low) to 21,571 (high) gay Catholic priests in the United States today.

By choosing to enforce silence, the institutional church pretends that gay priests and religious do not really exist. Because of this, there are no authentic role models of healthy, well-balanced, gay, celibate priests to be an example for those, young and old, who are struggling to come to terms with their sexual orientation. This only perpetuates the toxic shaming and systemic secrecy.

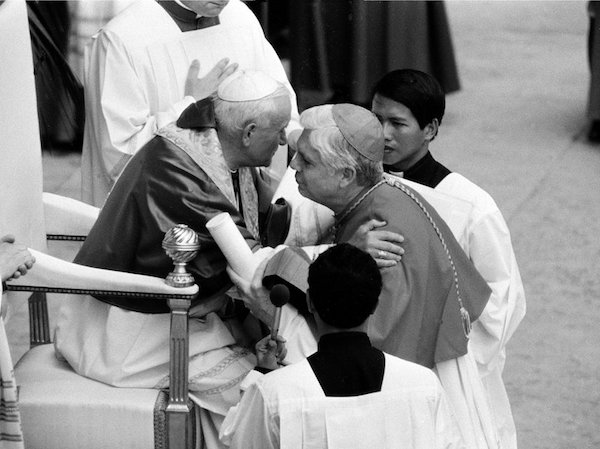

In 2013, Pope Francis shocked many Catholics when he answered a question about gay priests by saying, “Who am I to judge?” Francis has gone on to appoint archbishops and other senior church leaders who are more embracing of LGBTQ Catholics. However, in 2015, I wrote that while the pope deserves some kudos for his remarks and actions, much of the praise lavished on him is unwarranted. After all, the church continues to tolerate gay people more so than truly embracing them. The church continues to collectively hold archaic, bigoted views about transgender people. Moreover, the Vatican relentlessly clings to needless positions about women on issues like contraception that contribute to their subjugation around the world.

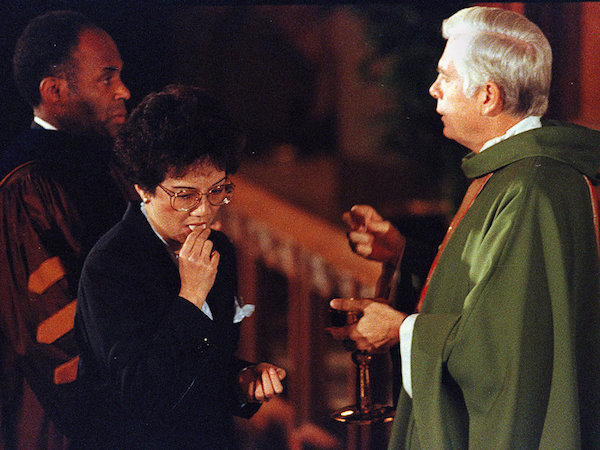

And for those reading this who might be thinking to quip that there aren’t that many black Catholics, think again. In November, The Atlantic published “There Are More Black Catholics in the U.S. Than Members of the A.M.E. Church.” The piece largely focused on the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops’ decision to create a new, ad hoc committee against racism in light of the white supremacist rally in Charlottesville, Va.

Although that is important work, I can’t help thinking about priests like Gregory Greiten and wondering why so much of the Catholic Church’s leadership continues to ignore what’s either hiding plain in sight or now demanding recognition.

Why can’t we engage in more meaningful dialogue about dogma, as in documentaries such as For the Bible Tells Me So or books such as God and the Gay Christian: The Biblical Case in Support of Same-Sex Relationships? According to the Pew Research Center, two-thirds of Catholics now support same-sex marriage. Those numbers will not dissipate with time. What is the church waiting on?

Greiten went on to write about his own role in perpetuating the stigmatization of LGBTQ people and the silence it has spurred in many of its members:

As a priest of the Roman Catholic Church currently serving in the Archdiocese of Milwaukee, I would like to apologize personally to my LGBT brothers and sisters for my part in remaining silent in the face of the actions and inactions taken by my faith community towards the Catholic LGBT community as well as the larger LGBT community. I pledge to you that I will no longer live my life in the shadows of secrecy. I promise to be my authentically gay self. I will embrace the person that God created me to be. In my priestly life and ministry, I, too, will help you, whether you are gay or straight, bisexual or transgendered, to be your authentic self — to be fully alive living in your image and likeness of God. In reflecting our God-images out into the world, our world will be a brighter, more tolerant place.

It would behoove the church to listen to him. I hope it will inspire more to step forward. The church should have priests who are women; chastity should be options; LGBTQ people should be able to join the priesthood if they feel such a calling. Everyone should be loved and embraced rather than merely tolerated, and as long as they aren’t seen as whole. Many of us have already been run out of the church because of its unwillingness to change. My mama may not be able to get me back to Mass, but perhaps Greiten and others like him can keep other kids from fleeing in the future.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!