Pope Francis has done more to reform the Roman Catholic church for a new age since Pope John XXIII convened the Second Vatican Council in the 1960s. The ferocity of opposition in U.S. Catholic conservative circles validates this assessment.

Francis acknowledged his growing opposition in off-hand remarks aboard the papal plane on Sept. 4, 2019. ABC News reported Francis as saying it is “an honor if the Americans attack me.”

But for all he is doing, he draws a line about the ordination of women.

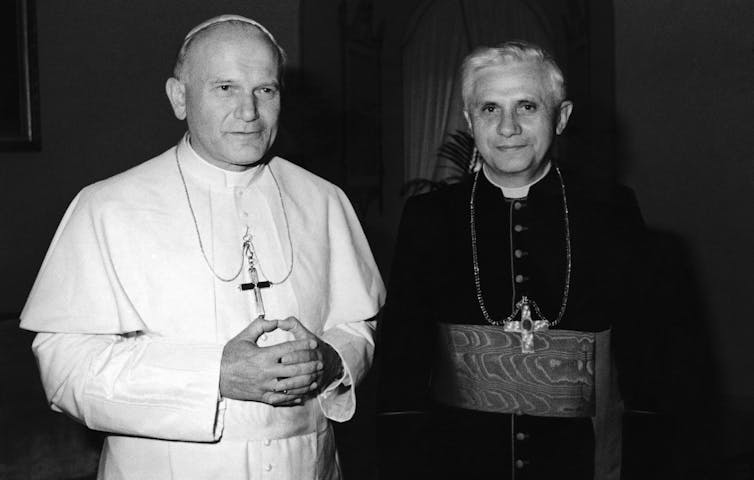

He has accepted the decision of Pope John Paul II who said, “I declare that the Church has no authority whatsoever to confer priestly ordination on women and that the judgment is to be definitely held by all the church’s faithful.”

That did not silence women’s ordination advocates in 1994, and there are even more voices clamoring for it today.

This may have paid off since the Vatican recently included a group lobbying for women’s ordination – the Women’s Ordination Conference — on a website promoting the two-year synod concluding in 2023. In other words, Francis wants to hear from them as well as many other Catholic advocacy groups.

And there’s the rub: Women’s ordination may be way off in the future. But some commentators believe that Francis’ small, incremental moves, like the WOC inclusion and regularizing the roles of lector and eucharistic minister for women, can make it easier for his successor to eventually ordain women though Francis has never acknowledged this objective.

Kate McElwee, executive director of the WOC, admitted to America Magazine that she was surprised the Vatican had accepted the group’s inclusion on the “Resources” site and said it showed “a lot of courage” from the synod office.

What took real courage, however, was the ordination of seven women as priests in the Catholic church by three bishops on a cruise ship on the Danube in 2007. That gave birth to a movement, mostly in North America, that has ordained about 200 women as priests to date. Still, it’s a drop in the bucket compared to the number of male priests totaling about 410,000 worldwide.

Other Christian denominations and Reform Judaism, meanwhile, have ordained women for decades.

The Vatican declared the 2007 and subsequent ordinations illicit and said the women declared themselves excommunicated by undergoing the ordination. But the church has stopped making such statements.

Validly ordained male bishops ordained the women to assure apostolic succession and while they are valid, the Vatican will not accept them.

Take the case of Ludmila Jararova, who was secretly ordained a priest in Communist Czechoslovakia back in 1970 for the underground church. Once the church could practice publicly, her male underground peers could continue as priests but she could not.

Author Jill Peterfeso has done an excellent job getting behind the movements that have fostered women for ordinations, the women priests themselves and the communities they lead outside the normal parish structure. In “Womenpriest,” published by Fordham University, one of her major conclusions is that these women do no want to simply be ordained like males.

Their credo, she writes, could be: “We have not walked away from Rome. We offer a new model of ordained ministry in a renewed Roman Catholic Church.”

These “womenpriests,” a word coined by the advocacy groups, resist the clericalism that has kept a patriarchal system in place and want more inclusion all across the board. And on the heels of major clerical sexual abuse scandals, which are still reverberating throughout the world, Peterfeso wrote: “If male priests’ bodies inspire fear and distrust, womenpriests’ bodies represent new potential.”

Without major reform, women are voting with their feet, concluded Peterfeso.

“While women’s attendance at Mass is higher than men, women’s declined twice as much as men,” she wrote.

And the decline among millennial women is significant.

“Nones” — those claiming no religion — are growing. Another group, A Church for our Daughters — an online program supported by about two dozen women’s equality groups — knows that justice and equality for women is still a potent movement and without inclusion of women in church leadership, young women will continue to walk away.

Pope Francis has appointed women to positions of greater authority than any previous pontiff. In 2019, 24 percent of employees at the Holy See were women, compared with 17.6 percent in 2010. When Sister Nathalie Becquart, a member of the Congregation of Xavières, was appointed the first woman undersecretary of the Synod of Bishops, she told reporters her appointment was evidence that “the patriarchal mindset [of the church] is changing.” Cardinal Tobin in Newark, who serves on the Vatican Synod Committee, has praised her accomplishments.

Charles Carr, my seminary classmate now in Philadelphia who left before ordination, said, “My personal vote would be for ordaining women as priests. If Eucharist, or union with Christ, is foundational for Christians to experience rebirth into a new life, then why would we not imagine the power of women to play this transformative sacramental role?”

And while most polls show Catholic overwhelmingly support ordaining women, Peterfeso reveals that more would prefer the institutional church ratify the change. As I approach 40 years as a priest, I have met many women who can lead.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!