— And now long for a ‘church for the nones’

By Perry Bacon Jr.

I ’m currently a “none” or, more precisely, a “nothing in particular.” But I want to be a something.

“None” is the term that social scientists use to describe Americans who say they don’t belong to or practice a particular religious faith. This bloc has grown from around 5 percent of Americans in the early 1990s to nearly 30 percent today. Most nones aren’t atheists, but what researchers call “nothing in particulars,” people who aren’t quite sure what they believe.

The majority of nones once identified themselves as Christians. About 40 percent of adults between 18 and 29 are nones, and so are plenty of people over 65 (around 20 percent). About one-third of those who voted for President Biden in 2020 are religiously unaffiliated, as are about 15 percent of people who backed Donald Trump. Nearly 40 percent of Asian Americans and more than 25 percent of White, Black and Latino Americans are nones. People without and with four-year college degrees are about equally likely to be nones. This group includes Americans from all regions of the country, including more than one-fifth in the “Bible Belt” South.

In their new book “The Great Dechurching,” Jim Davis, Michael Graham and Ryan Burge estimate that about 40 million Americans used to attend church but don’t now.

I could not have imagined when I was a kid or even a decade ago that I would be in this group.

![]()

During my childhood in Louisville my father was one of the assistant pastors at a small Charismatic church that my uncle still runs. Our family was at church every Sunday. Members often stopped by our house during the week to get advice from my father. His way of teaching me to drive was sitting in the passenger’s seat as we went to the midweek Bible studies he led.

Before I left for college, the congregation passed around a collection plate where they gave me several hundred dollars to congratulate and support me in my new adventure.

Once on campus, I attended church more than my peers, while enjoying the freedom of not being in services every Sunday. But in my 20s and into my 30s, I developed a religious life that wasn’t based on my father’s. I was a member of a few different nondenominational churches. (These were much smaller but similar in style to the churches run by prominent pastors such as Joel Osteen and Rick Warren.) I was at times quite involved: acting as a chaperone when the church youth group went on a trip; hosting a church-based small group at my house; even giving a sermon once.

I was never totally confident that there is one God who created the Earth or that Jesus Christ was resurrected after he was killed. But belonging to a congregation seemed essential. I thought religion, not just Christianity but also other faiths such as Judaism and Islam, pushed people toward better values. Most of the people I admired — from the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. to my parents — were religious. And I figured I might as well stick with Christianity, the creed I was raised in.

The churches I attended avoided politics, but I wasn’t out of step with them ideologically. Women served as pastors; there wasn’t any overt opposition to, say, gay rights or abortion. I suspect they were full of people who voted for Democrats. My childhood church in Louisville is overwhelmingly Black; the churches I attended as an adult are in the heavily left-leaning D.C. area and had a lot of attendees who worked in government and nonprofit jobs.

>The weekend after Donald Trump was elected in 2016, I remember one of the pastors declaring in his sermon that our church would remain a place that welcomed refugees and other immigrants. Everyone clapped.

But in the years after Trump entered office, left-leaning Gen X and older millennial Americans in particular abandoned church in droves, according to Burge, a political scientist at Eastern Illinois University and an expert on the nones. And I eventually became part of that group.

I didn’t leave church for any one reason. Inspired by the Black Lives Matter movement, I was reading more leftist Black intellectuals. Many of them either weren’t religious or were outright skeptical of faith. They didn’t view Black churches as essential to advancing Black causes today, even though King and many major figures in the 1960s civil rights movement had been very devout. I started to notice there were plenty of people — Black and non-Black — who were deeply committed to equality and justice but were not religious.

At the same time, my Republican friends, many of whom had been very critical of Trump during his campaign, gradually became more accepting and even enthusiastic about him. While my policy views had always been to the left of these friends, our shared Christianity had convinced me that we largely agreed on broader questions of morality and values. Their embrace of a man so obviously misaligned with the teachings of Jesus was unsettling. I began to realize that being a Democrat or a Republican, not being a Christian, was what drove the beliefs and attitudes of many Christians, perhaps including me.

And I couldn’t ignore how the word Christian was becoming a synonym for rabidly pro-Trump White people who argued that his and their meanness and intolerance were somehow justified and in some ways required to defend our faith.

I also came to a more nuanced understanding of my own life story. I had adopted the view from my parents and relatives that my rise from a middle-income household in which neither parent had a bachelor’s degree to Yale University and prestigious journalism jobs could have happened only with divine intervention. Perhaps that’s true. But an alternative explanation for my success was that I was the child of supportive, middle-class parents; they got me into some of the best schools in Louisville; and I did well in grade school, college and my jobs afterward.

Finally, something happened at church itself. One of the men who had been in the church group I hosted had sought to lead one himself. But a church higher-up told him that he could participate in church activities but not lead anything because he is gay. I had not realized the church had such a policy. I learned that my church would also generally not conduct weddings for same-sex couples

So between early 2017 and early 2020, I went from someone who clearly defined himself as a Christian and attended the same church most Sundays to someone who wasn’t sure about Christianity but was still kind of shopping for a new religious home and going to a service every few weeks. I wasn’t fully comfortable with the idea of vetting churches by their views on policy issues. I had never really done that before. (Perhaps I should have.)

“Your experience is very typical. Most people who disaffiliate do not cite a single precipitating factor. It’s more of a fading away from religion rather than a dramatic break,” said Daniel Cox, director of the Survey Center on American Life.

On this front, the pandemic was kind of a relief. Churches were mostly closed. I couldn’t continue my halfhearted search for a new one. I watched an Easter service online in April 2020, during the early stages of the pandemic. But over the past two years, I’ve been to church only a handful of times — even skipping Easter services.

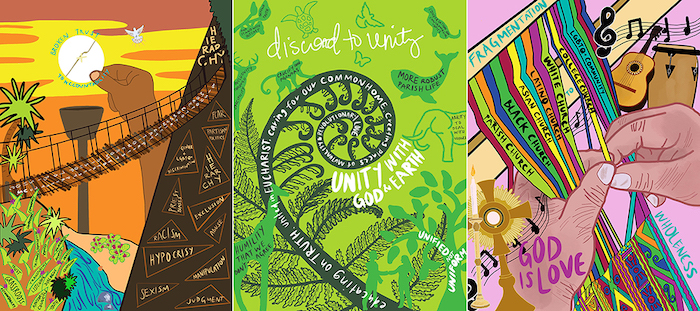

![]()

What’s kept me away is having a child. If I were childless, I think I would join a church to be a part of its community, and I would ignore the theological elements I’m not sure about. But my 3-year-old is getting more inquisitive every day. I don’t want to take her to a place that has a specific view of the world as well as answers to the big questions and then have to explain to Charlotte that some people agree with all of the church’s ideas, Dad agrees with only some, and many other people don’t agree with any.

I know I’m missing out on a lot, and I worry about denying Charlotte the church experience. Most sermons, theology aside, emphasize universal values such as kindness and generosity. I try to be a nice person, but weekly reminders and being part of a group that’s also trying to act in a compassionate manner is helpful. The churches I belonged to as an adult didn’t have a ton of Republicans, people in blue-collar jobs or people without college degrees, but there were some. So I met people who aren’t like me. People under 30 aren’t really in churches, but being a member of a church would be a great way for me to connect with more people over 50. (I’m 42.) I love live music and people singing collectively.

I know I could be a member of a congregation if I really wanted to. I could attend a Christian church on Sundays and teach my daughter about other beliefs the rest of the week. Or make churchgoing something I do alone.

People have told me to become a Unitarian Universalist. Unitarian churches that I have attended had overwhelmingly White and elderly congregations and lacked the wide range of activities for adults and kids found at the Christian congregations that I was a part of. But they have a set of core beliefs that are aligned with more left-leaning people (“justice, equity and compassion in human relations,” for example) without a firm theology.

I’ve also thought about starting some kind of weekly Sunday morning gathering of nones, to follow in my father’s footsteps in a certain way, or trying to convince my friends to collectively attend one of the Unitarian churches in town and make it younger and more racially diverse.

But I’ve not followed through on any of these options. With all my reservations, I don’t really want to join an existing church. And I don’t think I am going to have much luck getting my fellow nones to join something I start. My sense is that the people who want what church provides are going to the existing Christian churches, even if they are skeptical of some of the beliefs. And those who aren’t at church are fine spending their Sunday mornings eating brunch, doing yoga or watching Netflix.

An organization called Sunday Assembly, founded in Britain in 2013, has tried to launch nonreligious congregations around the world, including in the United States, but has struggled to gain much traction.

America today is a nation of believers (about 70 percent say they have some religious faith) who don’t regularly attend religious services (only 30 percent go to services at least once a month.) I’m the reverse: a person without clear beliefs about God who wants to go to something like church frequently anyway.

The Saturday farmer’s market in my neighborhood and a weekly happy hour of Louisville-area journalists provide some of what church once did for me: consistent gatherings of people with some shared values and interests. I’ve made new friends through both. And there are plenty of other groups and clubs I could join.

But none of those gatherings provide singing, sermons and solidarity all at once.

My upbringing makes me particularly inclined to see a church-sized hole in American life. But as a middle-aged American in the middle of the country, I don’t think that hole is just in my imagination. Kids need places to learn values like forgiveness, while schools focus on math and reading. Young adults need places to meet a potential spouse. Adults with children need places to meet with other parents and some free babysitting on weekends. Retirees need places to build new relationships, as their friends and spouses pass away.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!