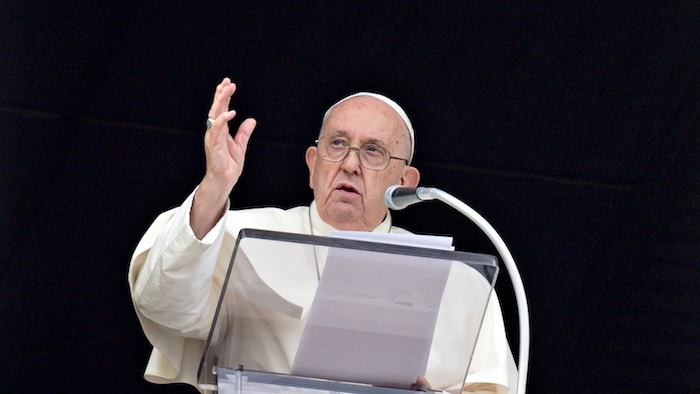

— Pope Francis has established himself as one of the most boundary-pushing popes the church has ever had. Here are his stances on same-sex marriage, trans people, LGBTQ+ parents, and more.

By

Every few months, many LGBTQ+ folks find themselves asking the same question: what is even the deal with the pope?

Since becoming the 266th leader of the Catholic Church in 2013, Pope Francis — née Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio — has established himself as one of the most boundary-pushing popes in modern history. That led a group of five cardinals to issue a list of concerns, or dubia, in October 2023 challenging some of his most radical positions on LGBTQ+ rights and other issues.

Still, in the Catholic church, “radical” is subjective. Francis has certainly taken many positions that soften Catholic doctrine when it comes to LGBTQ+ people and issues. That isn’t a hard thing to do, given that his predecessor Pope Benedict believes gay marriage will bring about the apocalypse and some leading bishops even lobbied against an LGBTQ+ suicide hotline. But Francis has also contradicted himself and split some very specific hairs regarding LGBTQ+ rights. And on a few issues, like the concept of transgender people, his principles are strictly orthodox.

With so many different statements released over the past decade, it can be hard to figure out what Pope Francis actually believes, especially about queer and trans people and how we live our lives and fit into the Church. Below, we’ve rounded up the highlights from Francis’ papacy so far to make sense of how Catholicism might slowly be changing, and in what ways it’s still the same old $30 billion tax haven we’re used to.

What is Pope Francis’s stance on gay people?

What is Pope Francis’s stance on gay people?

Francis has generally taken the open-ended position that God loves gays and wants them welcomed in the church. In 2013, the Pope famously said that “if someone is gay and is searching for the Lord […] who am I to judge?” The statement was widely lauded at the time simply for being the first time a pope had ever said the word “gay,” rather than “homosexual,” in public remarks. (Since then, Francis has frequently spoken of “homosexuals” in various comments.) In 2015, Francis affirmed the ministry of Bishop Jacques Gaillot, who was removed from his ministry in 1995 after he blessed gay couples. In 2018 Francis said that gay Catholics are made and loved by God, and in a surprise meeting at the Vatican in 2020, told families of LGBTQ+ youth that “God loves your children as they are.”

But while he has regularly affirmed queer love in the abstract, the pope has been less positive about what all those homosexuals might end up doing with one another. While “being homosexual is not a “crime,” as Francis exhorted in January 2023, he went on to say that “it’s a sin […] first let’s distinguish between a sin and a crime.” This seemed to contradict another statement Francis made in 2019, when he said the “tendencies” to be gay “are not a sin.”

In particular, Francis has said that queer relations between clergy members are a “serious concern” and “worry” him. “The question of homosexuality is a very serious one,” Francis said in a 2018 book interview, and there was “no room” for anyone in the ministry to enter a queer relationship (though heterosexual ones were still okay).

“In our societies, it even seems homosexuality is fashionable. And this mentality, in some way, also influences the life of the Church,” he fretted, recommending “persons with this rooted tendency not be accepted into ministry or consecrated life.”

Does Pope Francis support same-sex marriage?

Well, yes, but actually no. Francis is a vocal supporter of legal “civil unions,” but that’s as far from Church orthodoxy as he is willing to stray. This position dates back to his pre-papal days as Cardinal Bergoglio, when he was a leading proponent for a 2010 same-sex “civil union” bill in Argentina. As soon as that bill fell through, however, Bergoglio wrote a letter to the Carmelite Nuns of Buenos Aires to sound the alarm about another bill legalizing same-sex “marriage,” which was ultimately successful. The law would represent “the outright rejection of the law of God,” the pope-to-be wrote at the time, by “a ‘movement’ of the father of lies,” — i.e., Satan — “that seeks to confuse and deceive the children of God.”

After Kim Davis infamously refused to grant same-sex marriage licenses to gay couples as a Kentucky county clerk in 2015, claiming she acted “under God’s authority,” Pope Francis met with Davis that September during his visit to Washington, D.C. A Vatican statement asserted Francis only interacted with Davis as part of an audience with “several dozen persons,” and that their meeting “should not be considered a form of support of her position.” But Davis and her lawyers at the conservative Liberty Counsel have told a different story, saying Francis said he would pray for Davis, “thanked her for her courage and told her to ‘stay strong.’”

The pope has continued to ride this line for years, calling same-sex marriage “a contradiction” in some 2019 comments that LGBTQ+ figures roundly condemned. Francis doubled down in 2021, saying that since “marriage” is a God-delivered sacrament, the Church did not have the power to alter its definition. Civil unions can “help the situation” in a legal sense, he explained, but “marriage is marriage.”

As of now, Pope Francis still holds that “civil unions” are the only way to reconcile the religious and legal definitions of marriage. In his response to five conservative cardinals’ complaints in 2023, Francis expressed support for clergy (like Gaillot) who bless same-sex unions, but only if those blessings “do not convey a mistaken concept of marriage.” That privilege is still reserved for “a man and a woman” — specifically, the ones who are “naturally open to procreation.” Super.

What does Pope Francis think about transgender people?

Unsurprisingly, what the pope says about trans people doesn’t always match up with how he treats them. Francis is most infamously known among trans communities for comparing trans people to nuclear weaponry, comments that gave us the best flagging shirts of all time. “[G]ender theory […] does not recognize the order of creation,” Francis said in a 2014 interview, and thus “man commits a new sin, that against God the Creator” whose design “is written in nature.” Francis reiterated that concept in 2016, writing that trans youth “need to be helped to accept their own body as it was created” rather than physically transition.

In 2019, the Vatican distributed a memo entitled “Male and Female He Created Them,” a document which declared both trans and intersex identities “only a ‘provocative’ display against so-called ‘traditional frameworks’” that “seek to annihilate the concept of ‘nature.’” If you’re nonbinary, no you’re not: that idea is “nothing more than a confused concept of freedom in the realm of feelings and wants,” wrote Cardinal Giuseppe Versaldi in the memo, published by the Vatican Press. In early 2023, Francis went even further: “gender ideology, today, is one of the most dangerous ideological colonizations” in the world, he said, because “it blurs differences and the value of men and women.” Later in the year, he did make an allowance that trans people could receive baptism, but only if doing so would not cause a “scandal.”

But despite apparently seeing them as unnatural threats to divine creation, Francis has at least provided some amount of material support to trans people in need, particularly since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2020, Francis donated an undisclosed amount of money to a group of unhoused trans sex workers sheltering in an Italian church. Since then, he has gone on to meet with the same group at least five separate times, eating pasta with them and over 1,000 others at a lunch in November recognizing the Church’s World Day of the Poor.

For those trans people, the Pope is a major force for good, at least more so than he’s been viewed elsewhere in the world. “We transgenders in Italy feel a bit more human because the fact that Pope Francis brings us closer to the Church is a beautiful thing,” Carla Segovia told Reuters after the lunch. “Because we need some love.”

Does Pope Francis support LGBTQ+ parents and adoption rights?

On this, the Pope has taken a much clearer stance: not on your life. If a “marriage” is no longer between a man and a woman, then-Cardinal Bergoglio wrote in his 2010 letter to the Carmelite Nuns, adopted children will be irrevocably harmed from growing up with gay parents. “At stake are the lives of so many children who will be discriminated against in advance,” he lamented, “depriving them of the human maturation that God wanted to be given with a father and a mother.” (It should be noted that children raised by LGBTQ+ parents develop the same way their peers do, and may even have some advantages.)

Since becoming pope, Francis has not officially changed his stance. In 2013, a bishop reported that the pope was “shocked” by a civil union bill in Malta that would have allowed LGBTQ+ couples to adopt. The year after, Francis reiterated that children have “a right to grow up in a family with a father and a mother” and warned against being tempted towards “the poisonous environment of the temporary.” As comparatively boundary-pushing as some of his other views might be, we wouldn’t expect Francis to change on this one anytime soon.

Does the Pope at least like my pets?

Bad news! Owning pets is also a metaphysical threat to the fabric of reality, even for straights. “Many, many couples do not have children because they do not want to, or they have just one — but they have two dogs, two cats,” Francis said in 2022, calling the trend a “denial of fatherhood or motherhood” that “diminishes us” and “takes away our humanity.” We can only imagine what the guy thinks of Sapphics who own more than one litterbox.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Archdiocese puts pastor of Whitefish Bay and Fox Point parishes on leave, under investigation

— The Archdiocese of Milwaukee put a priest on administrative leave as it investigates an allegation of a consensual relationship.

Fr. Mark Payne serves in the senior Archdiocese of Milwaukee position of judicial vicar. He has also been pastor of two North Shore parishes since 2022: St. Eugene in Fox Point and St. Monica in Whitefish Bay. In addition, he is chaplain of the national TV Mass produced by Wisconsin-based Heart of the Nation.

Catholic news website “The Pillar” on Thursday, Nov. 30, first reported allegations that Payne was in an apparent relationship with another man, and the priest hired that man to teach at St. Monica School.

A day later, on Friday, the archdiocese announced it had pulled the pastor from the parishes and placed him on administrative leave.

SIGN UP TODAY: Get daily headlines, breaking news emails from FOX6 News<

City of Milwaukee property records, reviewed by FOX6 News, showed the priest and the other man co-owned a duplex near the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. It showed they bought the two-bedroom, two-bathroom home in 2003 for $245,000.

Courtesy: Heart of the Nation

As “The Pillar” also first reported, the other man was arrested in 2018 for an OWI and a second charge that was dismissed: possessing cocaine.

The criminal complaint, obtained by FOX6 News, noted that police alleged finding in the man’s pockets and wallet a total of seven baggies with a white substance that tested positive for the presence of cocaine. The complaint also said the man “admitted to using cocaine.” However, a Milwaukee County judge dismissed that charge as part of a plea deal. The complaint noted the man had been convicted of a separate OWI in 2016.

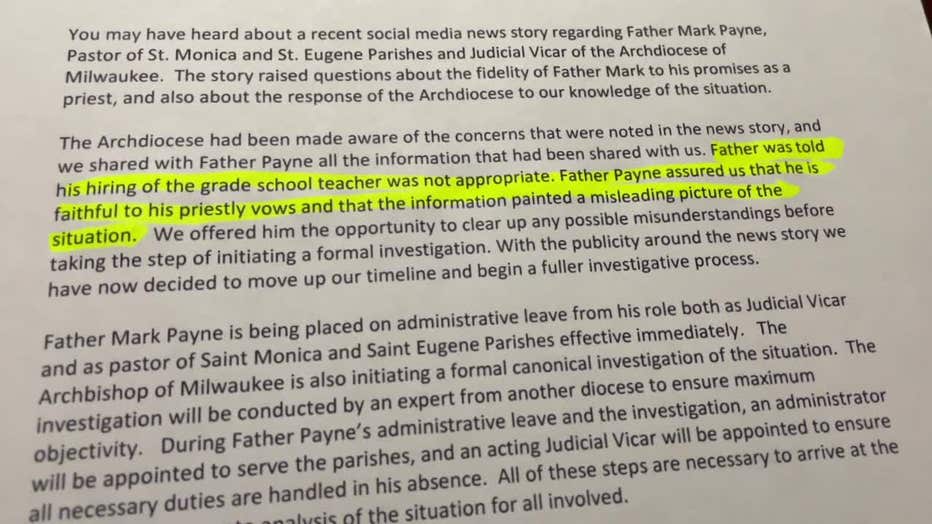

The archdiocese’s letter sent to parishioners on Dec. 1 declared: “Father was told his hiring of the grade school teacher was not appropriate. Father Payne assured us that he is faithful to his priestly vows and that the information painted a misleading picture of the situation.”

The Archdiocese of Milwaukee vicar for clergy, Fr. Nathan Reesman, wrote parishioners that the archdiocese had known about the allegations and was allowing Fr. Payne to “clear up any possible misunderstandings before taking the step of initiating a formal investigation.”

The archdiocese’s communications director, Sandra Peterson, added in an email to FOX that the archdiocese “had already been conducting an inquiry, and on Friday the archbishop called for a formal investigation. That’s the next step after an inquiry, so this was already in the middle of the process.”

In light of the story, the archdiocesan letter reported it moved up the timeline, as Archbishop Jerome Listecki launched a formal investigation to be led by an expert from another diocese “to ensure maximum objectivity.”

The archdiocese asked parishioners to “please pray for the next steps in this situation, for Father Payne, for his parish communities, and for all those impacted by this information.”

After news broke, the parishes wrote an email to parishioners on Saturday. It said the two parishes’ pastoral councils, finance councils and trustees met “to discuss how to move forward in light of the information learned yesterday.”

The email continued, “We ask for your patience as this process unfolds and also ask that we as parish communities pledge to not engage in gossip and speculation regarding the current situation and trust the investigative process undertaken by the archdiocese.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

‘The devil was in that building’

— New Orleans church orphanages’ dark secrets

Survivors of institutions run by Catholic diocese recall litany of sexual abuse as bankruptcy process keeps documents hidden

By Jason Berry

Call her Sheila.

She doesn’t want her name used because of court testimony she has given as a state social worker which helped put men who abused their families in jail. She’s retired now, but still a rescuer by nature.

On a recent afternoon she went back to Madonna Manor, the Catholic orphanage in a Spanish colonial revival building, now shuttered, several miles across the Mississippi River from New Orleans. “A reverent place,” she sighed, “but it’s also a crime scene.”

She gazed at the wooden plank covering a window. Raccoons now nested in rooms that were once the dormitory for boys under age 12 at Madonna Manor. Feral cats roamed the empty playgrounds where homeless men sometimes camped.

“I tried. I did everything I could to get that man put away,” she said, referring to Harold Ehlinger, who lived in a dormitory room when her day job was counseling boys at Madonna Manor decades ago.

On the opposite side of Barataria Boulevard, another Spanish mission structure housed the older, adolescent boys: Hope Haven, a name dripping with irony like candle wax given the hell described in victims’ lawsuits against the New Orleans archdiocese.

The buildings warped by neglect stand on vast green acreage – potentially sizable assets in the bankruptcy protection this archdiocese sought in 2020, facing abuse victim lawsuits. The church case now exceeds 500 abuse claims, whose potential value depends on the survival of a recent Louisiana “look-back” law which eliminated filing deadlines for victims.

The outlines of a subterranean criminal religious culture are emerging with roughly 100 abuse claims that center on the two orphanages.

The severity of suffering at Hope Haven and Madonna Manor probably explains why 23 of those claimants, already some of society’s most vulnerable and marginalized, have had legal troubles and been incarcerated – their cases are among those brought by the law firm of New Orleans trial attorney Frank E Lamothe.

“People escaped – sometimes in groups,” said a former resident, not among Lamothe’s clients, with his own lawsuit against the orphanages pending, under a pseudonym.

Call him Leon. Born in 1971, he was sent to Madonna Manor from a splintered family in late 1982 or 1983 – he’s blurry on exactly when. “Instead of taking abuse I’d run away – too many times to count,” he said. “Police would bring you back. It was pretty much a prison.”

A religious brother named Harold Ehlinger is accused of child sexual abuse in several lawsuits pending against the church and Catholic Charities, which ran the two facilities, while utilizing public funds from the United Way and local government.

In the fall of 1980, Sheila had a freshly minted master’s in social work from Tulane University when she went to work at Madonna Manor. In counseling and group therapy she discovered boys angry, cynical and acting out over sexual abuse by Brother Harold in his private room within the dorm. The boys agreed to give her statements – she taped interviews.

When Sheila rapped on his door, Ehlinger answered in a bathrobe, with a flustered child inside. Ehlinger was “furious at seeing me”, she recalled.

She told her supervisor. The supervisor had her meet with a priest who listened gravely and accepted her documentation. Ehlinger disappeared. She was relieved. In 1982, she took a better-paying job with the state of Louisiana.

Sheila the whistleblower had gone when Leon arrived. Church authorities had allowed Brother Harold to reside in a cottage near Hope Haven.

“Brother Harold was like the boss,” Leon continued. “Once you’re targeted they got lockdown units. They’d put a pillow over your face so you can’t hear what’s going on. Sometimes they wore masks to conceal [their] identity so you didn’t know who raped you.

“They’d bring you over to the Dark Tower – that’s what we called the church, the cathedral they had on the property. Running away from Madonna Manor you just wanted to be someplace else. You’re still going to an abusive environment, but it was the horrors of being sexually assaulted, like the devil was in the building.”

Leon’s lawsuit alleges beatings and sexual assaults by several men. “Brother Harold performed some form of fondling, groping or molesting of [Leon] on an almost daily basis,” the complaint alleges.

“When I got out,” he told the Guardian, “I was damaged goods.”

In the mid-80s, Sheila was driving past a Catholic school. She saw Ehlinger, surrounded by kids, guiding them into school buses. She was stunned. “I naively thought they’d turned him over to the police or kicked him out of ministry.”

Ehlinger was one in a procession of alleged pedophiles at Hope Haven and Madonna Manor, according to various pending lawsuits, depositions and documents from past cases not subject to bankruptcy judge Meredith Grabill’s secrecy order concealing church documents.

Collectively, those documents provide new, chilling particulars about two of the most infamous institutions linked to the Catholic clergy abuse crisis – but whose details have largely been buried in the past.

Ehlinger’s last known address is a Holy Cross religious house in Austin, Texas. A process server went to hand him legal papers there.

Ehlinger is among the more than 200 accused Catholic church abusers not on the local archdiocese’s “credibly accused” list, though the church resolved past cases identifying him in what became negotiated settlements.

The church declined the Guardian’s request for an interview with Archbishop Gregory Aymond or to answer general questions about this report.

Haunted by nuns

Call him Joe. His lawsuit against the church uses a pseudonym.

In 1976, when he was 11, Joe went to Madonna Manor. He noticed that the pool was closed.

“I was told one of the students drowned in the pool,” he said. “I never knew the boy’s name, only that he snuck out one night and died in the pool.”

Joe said he started wondering about the boy’s death after Sister Martin Marie began “tying me by the genitals and nearly suffocating me to sexually pleasure her between the legs”.

“She liked to sit on my face till I couldn’t breathe,” he remarked.

To this day, he said, he wonders about whether the boy who was said to have drowned may have been abused.

Martin Marie, a member of the School Sisters of Notre Dame, was named in an earlier wave of lawsuits over the orphanages in 2009. Like Ehlinger, her name is not on the archdiocese’s credibly accused list.

Joe finds that appalling because he says Sister Martin Marie wasn’t the only nun complicit in the beatings and sexual abuse he endured on the verge of puberty.

“I kept running away from Madonna Manor because of those nuns,” Joe said. “They sent me back to my mom and stepdad in Metairie. Things didn’t go well for me after Madonna Manor. My mom didn’t believe me about the nuns.”

Joe said he was committed to a mental hospital in Mandeville, a community across Lake Pontchartrain from New Orleans. He recalled being treated with the anti-psychotic medication thorazine. “I didn’t trust people,” he said. “I became very violent, I did fight the staff.

“I was held down, injected and put in restraints.”

He got out. After scrapes with the law he found a foster father, and slowly began rebuilding his life.

“I’m in a safe place now,” Joe said.

For many years he avoided Madonna Manor. But on a recent autumn day Joe gave a work buddy, who lived near the complex, a lift home. He found himself on Barataria Boulevard, and the memories started surging. He parked at the back of the Madonna Manor dormitory.

He found Sheila standing there.

Sheila saw the pain on his face and knew in a heartbeat he was a survivor. Like her, she sensed, he had left a piece of his heart there. Thinking of the boys she had tried to help, she stepped toward him and said: “Hi, I’m Sheila.”

“I’m Joe,” he replied. “I used to live here.”

She was a stranger but within a few minutes he was pouring out stories of his past – did she know about the boy who drowned? She did not. Sheila took the Madonna Manor job four years after Joe left. They exchanged phone numbers. He called her that night, sobbing as he let loose memories of the hell he survived, wondering if that boy who was rumored to have drowned was a victim like he was, only worse.

Joe continued by sharing details about his best friend at Madonna Manor, an altar boy who was molested by a priest.

The boy, Rene Perez, was eventually moved to another home across the lake.

“He and two or three others had run away,” Joe said. “They took bicycles and were going across [a] bridge when he got hit by a car and thrown in the water. They found him I think about five days later.

“The funeral was held at Madonna Manor church, but I wasn’t there that weekend.”

Still fighting tooth and nail

In the 1920s, Hope Haven opened as a home for dependent children. Madonna Manor opened a few years later. Eventually boys younger than 12 lived at Madonna Manor, and older teenagers at the other institution.

Exactly when the two institutions became a magnet for pedophiles and people prone to sadistic behavior is unclear. But 17 lawsuits filed in 2005 made allegations going back to the 1950s that described horrific abuses.

Besides the School Sisters of Notre Dame, other authority figures at the orphanages were Salesian priests and brothers, who founded the nearby Archbishop Shaw high school.

A major figure in the 2005 litigation, a priest named Ray Hebert, was director of the two facilities from 1966 to 1971.

Hebert, who held the elevated title of monsignor, was also the director of Catholic Charities, which had responsibility for the orphanages. If any cleric had textured knowledge of the internal dynamics at the two facilities, it was Ray Hebert.

In 2008, during the litigation, Hebert gave a deposition, saying: “If you were a trained social worker, you didn’t speak of orphanages.” Institutions for dependent children was more correct, he said, because state funding was involved.

Yet the survivors of the sexual and physical abuses may as well as have been on another planet from most of society. Most came from dysfunctional families and lacked any freedom to leave on their own, other than by running away, which invited retribution.

Hebert in the early 1990s took another job, as vicar of clergy at the New Orleans archdiocese, a position that required him to investigate priests accused of child sexual abuse.

Attorney Michael Pfau, who represented plaintiff-survivors of the orphanage, asked if Hebert ever reported a priest to the police or child protective services.

“No,” he answered. “I never did.”

Hebert stated that after interviewing a given priest, he sent a report to his boss at the time: the longtime archbishop Philip Hannan.

Pfau asked: “Did you ever ask a priest to sign a written statement?”

Hebert replied: “No, not that I remember. I recall one case, you know, where after interviewing the [priest] and taking notes, I did ultimately write up a report as to what I had learned from him, and asking him to go over the report to see whether he objected to anything I had put in that report not being accurate. But I didn’t ask him to sign this report.”

On retiring from that job in 2003, Hebert said he destroyed all his notes.

Doing so was a serious violation of canon law, according to Tom Doyle, a former priest and canon lawyer in the Vatican embassy in Washington DC in the early 1980s. Canon 1719 reads: “The acts of the investigation, the decrees of the [bishop] which initiated and concluded the investigation, and everything which initiated and concluded the investigation, and everything which preceded the investigation are to be kept in the secret archive of the [administration] if they are not necessary for the penal process.”

How many reports Hebert actually wrote is unknown. But his 4 November 1999 assessment of Father Lawrence Hecker was made public, in a recent filing by the Orleans parish district attorney’s office, after his criminal indictment.

The document is notable for Hecker saying he harassed or slept with various boys but did not have sex. Hecker does, however, concede that a young man “came out, years later, he told his parents that he and I had had sex together. They reported this to … Hannan and he spoke with me about it in early 1988.”

By 2012, when Sister Carmelita Centanni, the archdiocese’s victim assistant coordinator, wrote to Archbishop Aymond, she cited an allegation of sexual abuse against Hecker from the police in Gretna, a New Orleans suburb, stating: “This is the NINTH allegation we have on record against Larry Hecker.”

Hecker retired with the comfort of a church pension until it was discontinued after the New Orleans archdiocese’s bankruptcy. He has been in jail awaiting trial since his indictment in September.

In the 2005 Hope Haven-Madonna Manor litigation, three plaintiffs mentioned Hebert among other accused abusers. Hebert responded by filing his own lawsuit against the plaintiffs, alleging defamation and denying he ever abused anyone.

Two other plaintiffs also named Hebert among other abusers but had not filed suit at that stage. Ultimately, after the archdiocese settled the Hope Haven-Madonna Manor litigation for $5m, the plaintiffs who named Hebert withdrew their claims against him.

Religion News Service revealed a bitter divide at the time of the settlement. Some involved in the settlement wanted the church to be required to release all documents pertaining to abuse at Hope Haven and Madonna Manor, but that didn’t happen.

“We’ve had to fight the church tooth and nail for more than four years to get [the church] to acknowledge wrongdoing,” said attorney Roger Stetter, who also had clients in the litigation. Stetter accused the archdiocese of trying to hide evidence.

Archbishop Gregory Aymond, who was recently installed at the time, seemed conciliatory. “It’s important that these wrongdoers come to light and that we admit that as far as we can tell [the charges] are true,” he said.

But the church went on to underreport its list of abusers.

Between 2010 and 2020, the archdiocese settled more than 130 sex abuse claims, totaling $11.7m, in many cases requiring victims to sign confidentiality agreements – a move specifically denounced by the 2002 US bishops’ youth protection charter.

Hebert died in 2014. Several years later, there was a new wave of lawsuits against Hope Haven and Madonna Manor after Aymond published a list of New Orleans Catholic clergymen whom his archdiocese considered to be credibly accused of child molestation.

In January 2020, the archdiocese paid $325,000 to resolve a case that accused Hebert, Sister Martin Marie and others with ties to Hope Haven as well as Madonna Manor. The archdiocese would not pay such settlements if it didn’t consider claimants believable, as one of the organization’s vicars general told an abuse survivor in a separate case.

But Hebert’s name is conspicuously absent from the archdiocese’s credibly accused list, which has been updated several times since it was first published in 2018.

The issue no one wants to touch

Amid news of the later lawsuits, Joe contacted the attorneys John Denenea and Richard Trahant.

They told him the process could be long and frustrating. But he signed on.

After the bankruptcy began, Joe was surprised at the opportunity to serve on the creditors’ committee, representing other survivors and negotiating toward a settlement. He had few illusions about the church but wanted to help push against the rock of injustice.

Last year, he went to a scheduled meeting with Aymond, where he and three other survivors hoped to speak their truth directly to the archbishop. But then came word that Judge Grabill was removing him, Trahant, Denenea and three more of the lawyers’ survivor clients from involvement with the committee.

Grabill maintained that Trahant had violated a secrecy order by warning a local Catholic high school run by his cousin that the campus’s chaplain had a substantial stain in his past.

Trahant’s warning ultimately forced the archdiocese to disclose that the chaplain had engaged in sexual misconduct with a teenage girl at a past assignment in the 1990s but was allowed to continue his career.

“I think it was a setup by the church,” Joe said. He said his lawyers had long been after the records that vividly outline the abuses at Madonna Manor, Hope Haven and numerous other archdiocesan institutions across the New Orleans area, which serves about a half-million Catholics.

“The church doesn’t want to release that information,” Joe continued. “I think Richard [Trahant] was a patsy and they took us all out. That’s my take.”

The archdiocese’s formidable status in bankruptcy court leaves a trail of questions.

Given the public funds expended at Hope Haven and Madonna Manor, why haven’t federal authorities used their power to do a surgical review into every file archived at the archdiocese, including those detailing the abusive history of the two orphanages?

If Joe had cause to worry about whether a boy drowned there, and if his pal Rene Perez was the victim of a priest and died trying to escape another facility, what kind of oversight did Louisiana officials provide at Hope Haven and Madonna Manor?

Should the sadistic violence and rapes alleged by Leon be swept under the rug of time by the most powerful law enforcement authorities?

If Hebert, who oversaw the facilities, was in fact an abuser – as a $325,000 settlement would suggest – do documents shed light on his decisions that allowed the place to become a pedophiles’ haven, as alleged in the lawsuits?

How much do those 23 former Hope Haven and Madonna Manor residents who are now incarcerated know about what happened there?

Will Judge Grabill seal off information on crimes against children, as alleged in so many cases, to furnish a settlement when the church finally presents a reorganization plan?

More than half of New Orleans’s federal judges have recused themselves from archdiocesan litigation because of ties to the Catholic church.

This fact does not surprise Stephen C Rubino, a veteran plaintiffs’ lawyer who is now retired in Vermont. But that doesn’t mean Rubino – who spent many years in New Jersey litigating against the church – likes it at all.

“You should not be able to maintain a criminal racketeering conspiracy for hiding pedophiles and still function as a religious, tax-exempt charity,” Rubino – also a former Florida state prosecutor – said in response to the New Orleans archdiocese’s bankruptcy. “That is the issue no US attorney wants to touch.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Is door opening for women in the Catholic Church?

— Miami woman leading the call has new hope

By Lauren Costantino

For more than a decade, Ellie Hidalgo has been campaigning to expand the role of women in the Catholic Church.

The Miami woman is co-director of a nonprofit, Discerning Deacons, which invites other Catholics to consider ordaining women as deacons — a clergy role that has already been opened to married men. That would allow women for the first time in centuries to preach the Gospel, preside at baptisms, direct charitable services and perform other duties long confined to males.

From her past work, she knows the value women can add to the church. As a pastoral associate at a Jesuit parish near downtown Los Angeles, she worked with immigrant women from Mexico and Central America. In times of need, Hidalgo, who is trained in pastoral theology and fluent in Spanish, was called on to preach, assisting a priest who had trouble communicating with congregants. She’s also met with Catholic indigenous women in the Amazon region of Brazil who are on the front lines of defending human and land rights.

Hildago, who now attends Our Lady of the Divine Providence in Sweetwater, knows her devout Cuban grandmothers would never question why only men could serve pastoral roles. But that’s definitely not the case in conversations with her own nieces — they want to hear someone with “their own lived experience, from somebody who’s a sister or a daughter or a mother.“

Now, for the first time in years, Hidalgo can envision a day when the church might actually open some leadership doors to women.

Her hope springs from attending the Synod of Bishops, a monthlong assembly of church leaders in Rome that can shape future policy for the Catholic Church. The question of involving women in church leadership was widely discussed during the October gatherings, with a culminating report sending favorable signals for lifting some gender barriers in the future.

Although no concrete decisions were made this year, the tenor of discussions encouraged Hildago and others who share her goal for a more inclusive church. On the issue of ordaining women as deacons, the report called for continued research and discussion to be taken up at next year’s session.

“We were very pleased that that made it in there,” Hidalgo said. “It’s a very big step forward.”

The synod included 480 members appointed by Pope Francis from all continents. They participated in a process the church calls “conversations in the spirit.” It involved listening, praying and drawing up recommendations for the pope.

“What is the Holy Spirit asking of the church in the third millennium? What are the needs?” said Hidalgo. “In these times where we see a lot of profound woundedness in the world, more wars, and famine and drought and tons of migration — these were some of the topics that were being taken up. What is causing all that and how is the church to respond?”

Synod signals a possible shift

A synthesis report released by the pope appears to reflect a significant shift in centuries of resistance to putting women in leadership roles: “It is urgent to ensure that women can participate in decision-making processes and assume roles of responsibility in pastoral care and ministry.”

Along with considering making women deacons, other proposals called for the expansion of theological study and seminary programs to women. The report also said cases of labor injustice within the church need to be addressed, as women “are too often treated as cheap labour.” It also proposes expanding the responsibilities of a lector — someone who reads Scriptures during Mass — “to become a fuller ministry in the Word of God,” which in some contexts could include a woman preaching.

The role of women in the church has long been a divisive issue. But Miami Archbishop Thomas Wenski said that on many fronts, voting delegates agreed. Every paragraph included in the report must be approved by at least two-thirds of voting members — meaning the majority felt strongly about expanding women’s roles.

“There were many points of convergence – and so the Synod participants were not as divided as some looking in from the outside imagine,” Wenski wrote in an email to the Herald.

He said that many of the proposals involving women are already implemented in the United States.

“Our seminaries have women teaching on their faculties, some are involved in supervising seminarians in the pastoral assignments,” he said. “And they vote as other faculty members do … Our chanceries and our parishes do have women in roles of great responsibilities.”

The synod report also touched — often cautiously — on other lightning-rod issues, including immigration crises across the globe.

“In the face of increasingly hostile attitudes toward migrants, we are called to practice an open welcome, to accompany them in the construction of a new life and to build a true intercultural communion among peoples,” the report read.

There was a call to “to eradicate the sin of racism,” including within the church, though not much detail was given on how to do it.

And although there were discussions about LGBTQ people — Jesuit priest Father James Martin, for instance, was chosen as a synod delegate because of his commitment ministering LGBTQ Catholics — there were no official recommendations in the report.

Synod firsts for women

Still, the changes in this synod were significant. While past meetings consisted of solely bishops and cardinals, this year’s participants included priests, deacons, religious women and men, laymen and women and three young adults — the youngest was a 19-year-old student from the University of Wyoming. Out of the 363 voting members, 54 were women, a first in synod history.

“One of Pope Francis’ strong beliefs, and a belief of the synod process, is that the Holy Spirit can speak through anyone,” Hidalgo said. “We know that when Jesus chose his apostles, he didn’t go to the people you would expect. He went to fisherman.”

To ensure synod members heard each other’s perspectives, delegates were seated at round tables composed of clergy and lay people — a stark difference from the usual theater-style set-up more akin to lectures than discussions.

The changes reflected a papal mission to create a more unified church.

“Why do I insist on this?” Pope Francis said in 2021. “Because sometimes there can be a certain elitism … the priest ultimately becomes more a ‘landlord’ than a pastor of a whole community as it moves forward.”

Leading up to the assembly, millions of Catholics also participated in meetings at local parishes, praying together and discussing issues. It was the first time during a Synod of Bishops that everyone on all levels of the church was asked to participate.

In Miami’s listening sessions, people were concerned about declining membership, young people becoming less engaged in their faith and the lingering fallout of past clergy abuse scandals. Many wanted clearer answers on controversial issues that have divided the church.

There was positive feedback, too: the church providing a sense of belonging, admiration for priests dedicated to their mission and appreciation for the church’s ongoing commitment to charitable causes.

“Our own synodal process here locally has helped us look to the future with great hope,” Archbishop Wenski said. ‘”The Church in Miami is alive – we are concerned about many of the same issues that concerned the Synod members in Rome, but like them we acknowledge that God is in charge and we want to follow the Spirit’s lead.”

‘There is room for everyone’

Although Hidalgo was not a synod delegate, she traveled to Rome for associated public activities, spending a lot of time listening to the group of young adults who traveled with her organization.

“Young people I have listened to worry about their LGBTQ friends and family members, their divorced and remarried parents, the poor, migrants who face a hostile welcome, war-torn places, and our common home, the natural world,” she said. “They also want women to have more of a voice and to be at decision-making tables.”

At the opening Mass of the Synod in St. Peter’s Square in Vatican City, Hidalgo and the group of young adults donned T-shirts that read “En la iglesia hay lugar para todos!” It’s a reference to World Youth Day in Portugal when Pope Francis told the youth in Spanish, “In the Church there is room for everyone. Everyone, everyone, everyone.”

The words resonated with the 20-to 30-year-old Catholics, she said. They understand the struggles of those who feel like they don’t belong. In Rome, they listened to Pope Francis share this same message during his homily, this time in Italian.

“Come, you who are weary and oppressed, come, you who have lost your way or feel far away, come, you who have closed the doors to hope: the Church is here for you! The doors of the Church are open to everyone, everyone, everyone!”

Every Saturday night during the month-long synod, thousands of people gathered for a rosary prayer. The war between Israel and Hamas was top of mind for attendees, and the mood was somber, Hidalgo said. The bombing and mounting human deaths a reminder of the problems plaguing the world around them.

“We realized there’s so much at stake, not just for the church, but for the world. Our ability to figure out how to be peacemakers and how to resolve conflicts, and how to be able to dialogue about very difficult problems. Human lives are at stake.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

After global summit, Pope Francis injects synodality into Vatican theology

by Religion News Service

After a massive consultation of Catholics around the world and a Vatican summit to discuss the future of the church, Pope Francis has directed theologians to tread new paths, shift paradigms and embrace synodality.

In a decree issued Nov. 1, Pope Francis challenged the Pontifical Theological Academy — the body tasked with instructing Catholic theologians — to embrace an evolving theology that cannot be limited to “abstractly rehashing formulas and patterns from the past.”

“A synodal, missional and ‘outgoing’ church can only correspond to an ‘outgoing’ theology,” Francis wrote in the decree, also known as a motu proprio. “Theological reflections are hence called to a turning point, a paradigm shift, ‘a brave cultural revolution,’” the pope added, emphasizing such a theology must meet people in the concrete reality of their lives, culture and environment.

According to the theologian Leonardo Paris, who teaches philosophy at the Romano Guardini Institute of Religious Sciences, the new papal bull is asking theologians to help realize Francis’ vision for a church that is open to today’s realities.

“In the document we can see that the pope is aware of the need for theological tools that will ensure that synodality, and new questions that arise, are properly addressed,” Paris told Religion News Service on Tuesday (Nov. 7).

Pope Francis recently concluded the so-called Synod on Synodality, a monthlong (Oct. 4-29) gathering of Catholic bishops and lay Catholic faithful at the Vatican to discuss some of the most hot-button issues in the church. The lively conversations that occurred touched on LGBTQ inclusion, female ordination and the possibility of married priesthood, as laid out in a synthesis document published Oct. 28.

On many issues the synthesis called for continued study by experts and theologians, taking into account other disciplines, including science and psychology. Specifically, on the issue of whether women can be ordained deacons — who can preach at Mass but not hear confessions or celebrate the Eucharist — the synod assembly called for more theological research ahead of their next meeting in the fall of 2024.

In an interview with the Italian news channel TG1, Francis asked for a theology that could recognize that “the power of the Woman Church and of women in the church is greater and more important than that of male ministers. Mary is more important than Peter, because the Church is woman.” This aspect cannot be reduced to a simple question of ordination, the pope stated.

“I think the pope is being sincere,” Paris said. “It’s a complicated issue and the pope wants to offer an answer that isn’t simply cultural or emotional, but also theological.”

Pope Francis’ approach to theology has evolved over the years. When he was an archbishop in Buenos Aires, Argentina, he criticized theologians for being more concerned with abstract ideas than the real lives of people. In his 10 years as pope, Francis has often remarked that the “pueblo fiel,” Spanish for the faithful, have an infallible intuition on Catholic teaching.

“To know what to believe one must look to the authority, but to know how to believe one must look to the faithful,” explained Massimo Borghesi, a philosopher at the University of Perugia and author of “The Mind of Pope Francis: Jorge Mario Bergoglio’s Intellectual Journey.”

According to Pope Francis, when authority becomes separated from the faith of the people it falls into clericalism, the belief that clergy hold a higher status within the church. “The church breathes through two lungs, the institution and charisms, the people and the authority,” Borghesi said, laying out the pope’s views.

Francis’ answer to the separation between the hierarchy and the faithful is synodality — an openness to dialogue and encounter with those of differing experiences and perspectives — which he is attempting to inject into every aspect of the church, including theology.

Theology is called to be “a transcendent knowledge, which is at the same time attentive to the voice of the people, hence a ‘popular theology,’” Francis wrote in his decree. To do this, theologians must embrace dialogue with different traditions and religions, “openly engaging with everyone, believers and non-believers,” he added.

This is nothing new, according to Paris, who said this understanding of theology was already enshrined in “Lumen Gentium,” Latin for “Light of Nations,” the final document emerging from the Second Vatican Council in 1964. “Following the council, this is the direction that theology has undertaken, or at least attempted to,” he said.

Of course, he added, engaging with literature is easier for theologians than engaging with highly specialized sciences. “Understanding quantum mechanics is not exactly a walk in the park,” Paris said.

There is some pushback against Francis’ vision for a “theologian who smells of the flock,” Paris admitted. “Lately in the church there is a polarization that seems to suggest that engaging in contextual dialogue is something new,” he said, pointing to “theological, but also ideological and cultural tensions.”

In the interview, Pope Francis criticized reactionaries “who don’t accept that the church moves forward.” Instead, the church must grow “like the fruit of the tree, but always attached to its roots,” the pope said.

Francis has often quoted fifth-century St. Vincent of Lérins, who laid out a vision for the harmonious development of Catholic teaching that is “consolidated through the years, developed over time, refined by age.” On the death penalty, on slavery and even on atomic weapons, doctrine has changed, the pope said, suggesting there is no reason why it shouldn’t change some more.