By DAVID CRARY

Women have been elected heads of national governments on six continents. They have flown into space, served in elite combat units and won every category of Nobel Prize. The global #MeToo movement, in 15 months, has toppled a multitude of powerful men linked to sexual misconduct.

Yet in most of the world’s major religions, women remain relegated to a second-tier status. Women in several faiths are still barred from ordination. Some are banned from praying alongside men and forbidden from stepping foot in some houses of worship altogether. Their attire, from headwear down to the length of their skirts in church, is often restricted.

But women around the world in recent months have been finding new ways to chip away at centuries of male-dominated traditions and barriers, with many of them emboldened by the surge of social media activism that’s spread globally in the #MeToo era.

Millions of women in India this month formed a human wall nearly 400 miles long in support of women who defied conservative Hindu leaders and entered an important temple that has long been off-limits to women and girls between the ages of 10 and 50.

In Israel, where Orthodox Judaism has long restricted women’s roles, one Jerusalem congregation has allowed women to lead Friday evening prayers. Roman Catholic bishops, under pressure from women’s-rights activists, concluded a recent Vatican meeting by declaring that women, as an urgent “duty of justice,” should have a greater role in church decision-making.

Many feminist scholars are challenging the rightfulness of long-standing patriarchal traditions in Christianity, Judaism and Islam, calling into question time-honored translations of verses in the Bible, Torah and Quran that have been used to justify a male-dominated hierarchy.

Social media is seen as a big catalyst in boosting activism and forging solidarity among women of faith who seek more equality. The #MeToo movement has been evoked — even in the ranks of conservative U.S. denominations — as a reason why women should expect more respectful treatment from male clergy, and a greater share of leadership roles.

“Women are looking for opportunities to have their voices heard and be more effective in their religious traditions,” said Gina Messina, a religion professor at Ursuline College in Ohio who describes herself as both a feminist and a Catholic theologian. “Using social media is an opportunity to say what they think.”

She co-founded a blog called Feminism and Religion that has scores of contributors around the world and followers in more than 180 countries. She also co-edited a collection of essays by Christian, Jewish and Muslim women explaining why they haven’t abandoned their patriarchal-leaning faiths.

“The perception seems to be that it is a feminist act only to leave such a religion. We contend that it is also a feminist act to stay,” the three editors write in their foreword.

Here’s a brief look at the status of gender equality in several of the world’s religions:

ROMAN CATHOLICISM

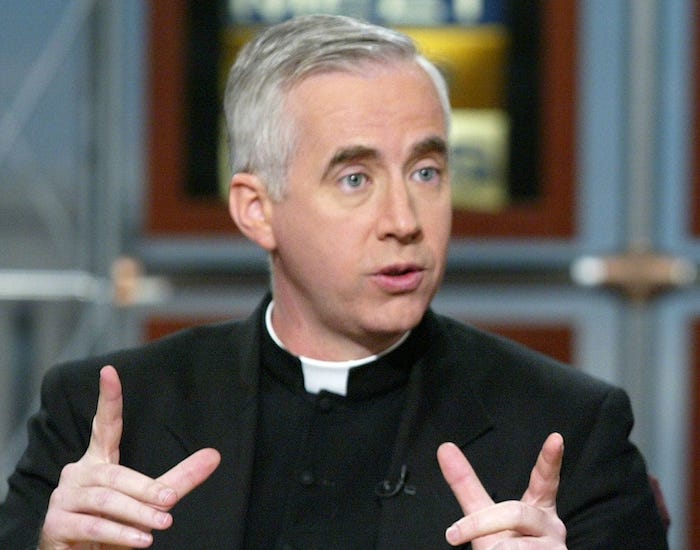

Catholic doctrine mandates an all-male priesthood, on the grounds that Jesus’ apostles were men.

A decades-long campaign for women’s ordination has made little headway and some advocates of that change have been excommunicated. Women do play major roles in Catholic education, health care and parish administration

While the recent meeting of bishops at the Vatican produced a call to expand women’s presence in church affairs, no details were proposed. The seven nuns who participated along with 267 male clergy were not allowed to vote on the final document.

Earlier this year, a Vatican magazine published an expose detailing how nuns are often treated like indentured servants by cardinals and bishops, for whom they cook and clean with little recompense.

At the University of Dayton, a Catholic school in Ohio, religion professor Sandra Yocum says some of the young women she teaches “are having a hard time seeing where they fit in” as they assess the church’s doctrine on gender roles and its pervasive clergy sex-abuse scandals.

“They have a deep concern for the church,” she said. “They want to respond in some way and take a leadership role.”

Messina sometimes engages in “small acts of dissent” to show displeasure with patriarchal Catholic traditions. At the recent funeral for her grandmother, she changed a Bible reading to make the passage gender-neutral.

“We have to continue to push — regardless of whether it’s in our generation or five generations from now.”

Rose Dyar, a senior at the University of Dayton, says she’s determined to team with other young Catholics to help the church overcome its challenges. The ban on female priests isn’t enough to drive her from Catholicism, but it dismays her.

“I absolutely support women’s ordination,” she said. “Unfortunately I don’t foresee it happening anytime soon, and that breaks my heart.”

ISLAM

Some of the most important traditions and practices of the Prophet Muhammad were preserved and carried forth by the women closest to him— his wives and daughters. But as with many other major faiths, women in Islamic tradition have largely been relegated to supporting roles throughout recent history.

Women in Islam do not lead prayer or give traditional Friday sermons. In larger mosques where women are welcome, they are almost always segregated from men in the back or allocated spaces on other floors with separate entrances and exits.

In Saudi Arabia, a male-dominated interpretation of Islam bars women from traveling or obtaining a passport without the consent of a male guardian. Only this year did the kingdom allowed women to drive.

Changes are happening elsewhere. In Tunisia, President Beji Caid Essebsi has proposed giving women equal inheritance rights with men — a much-debated topic around the Muslim world. In the Palestinian territories, Kholoud al-Faqih became the first female Shariah court judge in 2009, in part to help women beset by domestic violence.

Some women are challenging interpretations that state only men must attend traditional Friday prayers. A few have chosen to create their own prayer spaces, like the Women’s Mosque of America in California where women lead the services and female scholars share their knowledge.

The bylaws for that mosque were drafted by Atiya Aftab, who teaches Islamic Law at Rutgers University and is chair of the board at her mosque — a first for a woman in New Jersey. She says moves in the U.S. to expand women’s roles in the Islamic community have sometimes been met with conservative backlash, but the momentum for change seems strong.

In Texas, Muslim women recently formed a group that has investigated and publicized instances of sexual, physical and spiritual abuse committed against women by Muslim community leaders.

JUDAISM

The gender situation within Judaism is markedly different in Israel and the United States, which together account for more than 80 percent of the world’s Jewish population.

The largest U.S. branches, Reform and Conservative, allow women to be rabbis, while the Orthodox branch does not. In Israel, the Conservative and Reform movements are small, and Orthodox authorities hold a near monopoly on all matters regarding Judaism.

One major source of contention: the Orthodox-enforced policy of prohibiting women from praying alongside men at the Western Wall in Jerusalem, the holiest site where Jews can pray. Numerous women protesting the policy have been arrested, and several American Jewish groups were angered last year when Israel’s government backtracked on plans to expand a space where both men and women could pray.

However, there have been moves to expand Orthodox women’s roles in religious life. A Jerusalem congregation, Shira Hadasha, has adopted a liberal interpretation of Jewish religious law that incorporates women’s involvement in services, such as leading Friday evening prayers and reciting from the Torah on the Sabbath.

An Orthodox organization called Tzohar is trying to advance women in roles where social custom, not religious law, has excluded them — such as teaching Jewish law or certifying restaurants’ compliance with kosher standards.

“If Jewish law does not say that something is prohibited, but just because of social or cultural reasons women were not involved, we see no reason that they should not be involved, said Tzohar’s chairman, Rabbi David Stav.

MORMONISM

Women in the Mormon church are barred from being priests, leading local congregations or holding the top leadership posts in a faith that counts 16 million members worldwide.

The highest-ranking women in the church oversee three organizations that run programs for women and girls. These councils sit below several layers of leadership groups reserved for men.

The role of women in the conservative religion, officially named The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, has been a subject of debate for many years, with some members pushing for more equality and increased visibility for women.

The church has made some changes in recent years; women’s groups say they mark small progress. In 2013, a woman for the first time led the opening prayer at the faith’s semiannual general conference in Salt Lake City. Later that year, a conference session previously limited to men was broadcast live for all to watch.

Mormon women are still expected to wear skirts or dresses to worship services and inside temples, but the religion has loosened its rules in recent years to allow women who work at church headquarters to wear pantsuits or dress slacks and to let women serving proselytizing missions to wear dress slacks.

The church shows no signs of budging on women’s ordination. Kate Kelly, the founder of a group called Ordain Women that led protests outside church conferences, was expelled from the faith in 2014.

“We’re in it for the long haul,” said Lorie Winder Stromberg, 66, a member of Ordain Women’s executive board. “I think women’s ordination is inevitable — but I have no sense of the timing.”

HINDUISM AND BUDDHISM

The gender-equality situation in these two Asian-based faiths is difficult to summarize briefly. Neither has a single supreme entity that enforces doctrine, and each has multiple branches with different philosophies and practices.

In Buddhism, women’s status varies from country to country. In Thailand, a Buddhist stronghold, women can become nuns — often acting as glorified temple housekeepers — but only in 2003 won the right to serve as the saffron-robed full equivalents of male monks, and still represent just a tiny fraction of the country’s clergy.

India’s Sabarimala temple had long banned women and girls of menstruating age from entering the centuries-old house of worship. Some Hindus consider menstruating women to be impure.

The Supreme Court in September lifted the ban, and violent protests broke out after women entered the temple. Earlier this month, women formed a human chain spanning than 600 kilometers (375 miles) to support gender equality.

“The Hindu temples at present have almost 99 percent male priests,” said women’s rights activist Ranjana Kumari, director of New Delhi-based Center for Social Research. “Things have to improve.”

SOUTHERN BAPTISTS

While many Protestant denominations now ordain women, the largest in the U.S. — the Southern Baptist Convention — is among those that don’t. It advocates that women submit to male leadership in their church and to a husband’s leadership at home.

Southern Baptist leaders say this doctrine aligns with New Testament teaching. One passage they cite quotes the apostle Paul as writing, “I do not permit a woman to teach or to have authority over a man.”

A recent statement from SBC leadership insisted that Southern Baptists “are not anti-woman.”

“However, because Scripture speaks specifically to the role of pastor, churches are under a moral imperative to be guided by that teaching, rather than the shifting opinions of human cultures.”

Cheryl Summers, a former Southern Baptist who has challenged the church to improve its treatment of women, describes this gender doctrine as “tortured logic” — especially given the accomplishments of SBC women in the secular world.

“There’s tremendous cognitive dissonance for a woman of faith who is leading professionally or through volunteer efforts when she experiences the glass ceiling and walls in her place of worship,” Summers said via email.

For the past year, the SBC has been roiled by a series of sexual misconduct cases involving churches and seminaries, prompting some activist women to demand new anti-abuse policies.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!