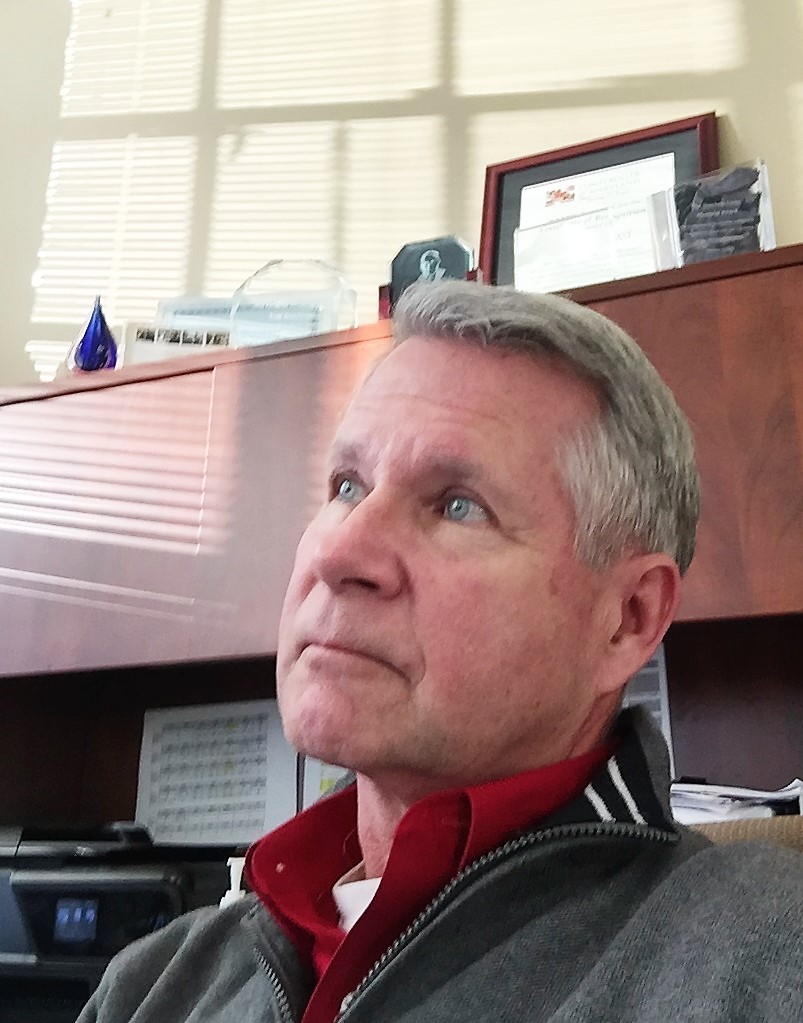

God, what are you calling me to do here, prayed the priest. Come out, or stay in the closet?

After 23 years in Chicago parishes, the question had pushed its way to the surface.

He weighed his options. He thought about his parishioners. Many, he knew, were accepting of gay people, even of same-sex marriage, but others — less so. He had grown up in a large Catholic family; he understood what people’s faith meant to them. He didn’t want to harm his flock, or the Catholic Church.

He wondered if he could be penalized in his job. And, in truth, he considered his status. He knew many Catholics had what he might call a romanticized view of the priesthood: Priests are supposed to be pure, almost above the world of sexuality, selflessly willing to give up creating a family of their own to serve God. This would mean falling from that pedestal.

Then, he weighed these factors against the impact his coming out could have on the lives of young gay people in treatment for addiction or who are suicidal, on the parents and grandparents who feel they must choose between their gay child and their church. For some, knowing their priest is gay — and at peace with it — could be healing, he felt.

He thought of his complex feelings. He had no ax to grind, and he wasn’t an advocate.

He set the rules at the outset: He did not want to be identified in this article. But at the end of the first conversation, he said: I’m leaning towards using my real name.

At a time when the phrase “coming out” is starting to sound almost quaint, the Catholic priesthood may be one of the last remaining closets — and it’s a crowded one. People who study gay clergy believe gay men make up a significant percentage of the 40,000 ordained priests in the United States, including some who believe they may even be the majority. Meanwhile, the number who are out is minuscule.

The Catholic Church is in the throes of a historic period of debate about homosexuality. Between Pope Francis’s now-famous “Who am I to judge?” line and two high-profile, global meetings he called in the past year to open up discussion about sex and family, there has perhaps never been as much dialogue among Catholics about how far to extend the welcome mat to gay people.

Francis is expected in the next couple of months to release his conclusions from the meetings. Both sides claimed a measure of victory two weeks ago when he told a Vatican court that “there can be no confusion” between the family willed by God and any other type of union. To some, it was a sign that Francis will not give a doctrinal inch; others saw it as evidence that he might not put up a fight on civil unions.

Gay priests are invisible in this debate; the church does not research the topic. However, interviews with a dozen priests and former seminarians who are gay, and experts on gay priests, reveal a group of men mostly comfortable with their sexuality. Many express no urgency for the church to accept it. Some, however, say the priesthood remains sexually repressive; one said there is an “invisible wall” around the topic among priests.

This is in part, they say, because as priests they vowed to put service to God over all else.

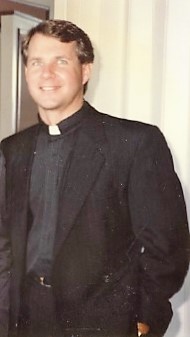

The Rev. Warren Hall decided to join the tiny number of out priests after he was removed as campus minister of Seton Hall University last May. Officials noted he had supported a group on Facebook that advocates for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and racial justice.

But while Hall has since been outspoken about the need for more tolerant, open dialogue about human sexuality, he said he understands why gay priests don’t come out — or see gay rights as their cause.

“Priests want to be good priests, they want to do their job,” said Hall, who was reassigned to a Hoboken, N.J., parish. “More priests are rightfully more concerned about homelessness versus getting caught up in something about sex. We should be more concerned about those issues [like homelessness] that are impacting people.”

But some also fear the consequences of coming out in the Catholic Church, whose hierarchy frames a gay life as a diversion from God’s ideal. Parts of church teaching call being gay “objectively disordered.”

The Chicago priest remembers wanting to speak from the pulpit when same-sex marriage became legal in California in 2008. But he talked himself out of it. “I thought: ‘Oh my gosh, if I talk about it, they’ll think I’m gay.’ ”

He is torn as he watches the spike in dioceses firing employees who marry someone of the same gender, but his instinct has been to defer to the church.

“I have a problem with Monday-morning quarterbacking. There’s always stuff you don’t know about why people are fired,” he said. It grates on him, though. “But where do you draw the line? There are all kinds of folks not in line on morality stuff.”

Priests who have come out — in some cases citing the need to confront anti-LGBT discrimination — say they have found scant support among other priests.

“Parishioners were very supportive. Religious women were very supportive. One group that was silent were my brother priests. Gay as well as straight,” said the Rev. Fred Daley, a Syracuse, N.Y., priest who came out in 2004 after he was angered by people blaming gay priests for the global clergy sex abuse crisis. “In a sense, it was like I sort of broke the rules of the clerical club.”

The mixture of fealty to God and the church and concern about harming parishioners or their standing in the priesthood has led some gay priests to gauge each situation before opening up.

A New York priest says he comes out only in rare private circumstances, when counseling someone struggling to accept their homosexuality. “I’ve been in multiple situations where someone will say: ‘I’m a piece of s—.’ I’ll say: ‘Do I look like a piece of s— to you? God made me this way.’ ”

A Pennsylvania priest says he’s “quietly subversive,” speaking acceptingly of gay people but not to just anyone. Even the confessional is not a truly safe place for him to tell someone who is gay that it’s not a bad thing. “We have too much to lose. I’ve invested my life in this business.”

Priests’ views of the church’s handling of homosexuality are not uniform. Some blamed Catholicism for the decades it took them to accept themselves. Others credited their training and the help of other priests with their self-knowledge, saying homophobia in the non-church culture is the problem.

Even as the doctrine banning same-sex relationships has not changed, the church has varied its emphasis and message on the topic.

The most recent authoritative statement came in 2005, from Pope Benedict XVI, who, seeking to clarify doctrine after the sweeping changes under the Second Vatican Council, wrote that being gay is “objectively disordered.” The church, “while profoundly respecting the persons in question, cannot admit to the seminary or to holy orders those who practice homosexuality, present deep-seated homosexual tendencies or support the so-called ‘gay culture,’ ” Benedict said,

The message seemed clear, say many priests and several people who train seminarians. Many who had considered coming out of the closet decided to stay in.

Yet the intent behind Benedict’s words has been debated. Some say he never meant to bar gay men who are celibate. Others say he meant to keep out men who feel strongly defined by their sexuality, and perhaps would be challenged by celibacy.

Regardless, there is no question that in the past few years church leaders are emphasizing far more that Catholicism accepts people who are gay — it’s the sexual relationships or marriage that is the problem. Francis’s famous “Who am I to judge?” comment was said after a question about gay priests.

Last spring, a Jesuit — Francis’s community — wrote about being gay in a blog post believed to be the first time a Jesuit has come out with the explicit permission of his superiors. Damian Torres-Botello denied requests to be interviewed for this article.

In some communities, particularly the Jesuits, gay priests can be out — to a point, the priests interviewed said. Others say Benedict’s words created a lasting chill for gay men and that conditions are much harsher today.

“If there is a seminarian who is gay, my recommendation would be: Don’t tell anybody,” Hall said.

Monsignor Stephen Rossetti, a D.C. priest-psychologist who helps seminaries create materials about sexual health, said there is a hesitancy today to admit people who are gay and that the percentage of gay priests has dropped. All other priests interviewed disagreed.

“They’re more conservative, but no less gay,” said the Pennsylvania priest of the incoming, younger generation of clergy.

The Chicago priest doesn’t disregard the church’s teaching on sexuality, but he tries to emphasize the church’s teaching that sexuality is an expression of the divine and encourages people topray and discern their own place. His place, he says, is that of a man who didn’t understand he was gay when he entered the priesthood and now views his sexuality as a gift to his ministry.

“There’s a level of witnessing here that’s important for me to do. The Christian faith has a lot to say about the underdog, about the marginalized or the leper, the blind, the lame, the ostracized woman prostitute, widow, the little one,” he said.

“I’d like to be one of those priests, who, with great respect for the church’s teaching, can say: I’m a human being. I’m a son — one of six — I’m gay and I’m a priest, period.”

Prayer has led him to believe this article is part of that witness. He has decided he wants to be known: His name is Michael Shanahan.

Complete Article HERE!