The Catholic Church and Sexuality: If Only the Hierarchs Would Listen and learn

COMMENTARY — John Falcone

Few Roman Catholic seminaries can boast an active and vibrant GLBT student organization. Boston College’s School of Theology and Ministry is one. Since April 2011, the “GIFTS” group (“G/L/B/T Inclusive Fellowship of Theology Students”) has planned and hosted prayer services for the school community. We’ve celebrated the long tradition of believers who have lived their Catholicism through same-sex love, non-traditional gender roles and the quest for social justice. We have also asked some difficult questions: How can GLBT lay people with a proven calling to ministry best serve the Catholic Church? What is our responsibility to a clergy and leadership which is often homophobic and paternalistic, and profoundly conflicted about sex?

Recently, four GIFTS members and I drove to Fairfield University in Connecticut for “The Care of Souls: Sexual Diversity, Celibacy and Ministry” — the last of this autumn’s “More than a Monologue” series on sexuality and the Catholic Church. We went to hear Rev. Donald Cozzens, a respected researcher on the Catholic priesthood and a former seminary president; Mark Jordan, a queer theologian and ethicist at Harvard Divinity School and Jeannine Gramick, a Catholic nun who was silenced by the Vatican for her work with lesbians and gays. We found four themes particularly compelling: the struggles of a closeted clergy, the dynamics of Catholic patriarchy, the troubling theology of priestly vocation and the powerful Christian witness offered by lesbian nuns.

Recently, four GIFTS members and I drove to Fairfield University in Connecticut for “The Care of Souls: Sexual Diversity, Celibacy and Ministry” — the last of this autumn’s “More than a Monologue” series on sexuality and the Catholic Church. We went to hear Rev. Donald Cozzens, a respected researcher on the Catholic priesthood and a former seminary president; Mark Jordan, a queer theologian and ethicist at Harvard Divinity School and Jeannine Gramick, a Catholic nun who was silenced by the Vatican for her work with lesbians and gays. We found four themes particularly compelling: the struggles of a closeted clergy, the dynamics of Catholic patriarchy, the troubling theology of priestly vocation and the powerful Christian witness offered by lesbian nuns.

For Cozzens, the Vatican’s prohibition of gay men entering the priesthood has worked much like the (now defunct) policy of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell.” Gay men have not left the priesthood (Cozzens estimates they make up 30-50 percent of US priests), and they also continue to enter — either by lying about their orientation, or by keeping it under wraps at the direction of seminary directors. Yet gay priests must steer firmly clear of their sexual identity in their preaching and public personas. As GIFTS member Oliver Goodrich asked, “How can so many priests, who preach a gospel of liberation and authenticity, lead such inauthentic lives?”

Jordan was more provocative. In a church that defines “the few and the proud” as its straight male celibate clergy, power gets tangled with maleness. But the clergy’s desire for power animates an unseemly dance of dominance, submission and career advancement. Within all-male hierarchical settings, this can smack of sado-masochist pleasures. Accepting gay men into seminary, or acknowledging same-sex love, shines an unwelcome light on these homoerotic dynamics. To keep this psychology intact and in shadow, the hierarchy must keep gay men (and straight women) out.

The notion that ritual and organizational leadership requires abstinence from sexual love is another problem for Catholic ministry. For almost 2000 years, Catholic monks and nuns have accepted celibacy as a form of spiritual practice. For 1100 years, Catholic priests could marry and raise children. Today, Church officials insist that everyone called to the priesthood automatically receives the “grace” (or spiritual power) to live a celibate life. Why must these two be connected? As Jocelyn Collen, another GIFTS member, remarked, “Grace is not given to someone on command. No one — not even the Vatican — can direct the grace of God.”

Gramick’s reflections were perhaps the most hopeful. Drawing from decades of work with lesbian nuns, she described a non-patriarchal model of ministry in which warm and affirming female friendships support lives of celibacy, service and prayer. For these nuns, the experience of sexual orientation is about the longing for intimacy, the romantic desires that shape personality and interpersonal life. This makes profound psychological sense. Lesbian and gay celibates need intimate same-sex friendships; in the same way, straight men called to celibacy need warm and affirming relationships with women. Without such intimate friendships, frustrations multiply, boundaries decay and ministers tragically act out.

At the end of the day, we drove back to Boston through the worst October snowstorm in years, and a certain chill still remains. I’ve co-written this article with another GIFTS student, whose goal is to teach in a Catholic school. The insights of this minister-in-training are all over this article. But to protect his/her future employment, I cannot disclose a name. Like the prayers that GIFTS has written, and the GLBT saints that we’ve recalled, the insights of marginalized Catholics speak of Spirit, courage and truth. Our hierarchs should listen and learn.

Complete Article HERE!

Vatican moved quickly to punish Gumbleton

Bishop Thomas Gumbleton, a retired auxiliary bishop of Detroit, revealed for the first time yesterday details about his removal as a parish pastor in 2007. NCR published a report of the talk Gumbleton delivered at pre-conference meeting of Call to Action in Milwaukee.

Gumbleton had followed the sex abuse crisis in the press, especially the church’s response. “I thought they were starting to move along.”

The bishops had developed the Dallas Charter in 2002, outlining policies for dealing with sexual abuse cases.

“I can remember actually being at the press conference when they announced the charter and they said ‘and now the whole problem is behind us,'” Gumbleton said. “They really talked like they had settled this whole thing.”

“It’s not over and it won’t be over until we within the church deal with it in a very open, honest and thorough way,” he said. “And that’s going to take much change within the church.”

After being lied to in the past by a fellow bishop who said he had taken care of an abusive priest when in fact he hadn’t, Gumbleton “was totally upset, disillusioned even when I discovered how easily he could put me off, tell me ‘I’ll take care of it’ and then do nothing.”

Barbara Blaine of SNAP, a longtime friend of Gumbleton, asked him if he would testify on behalf of SNAP for a statute of limitations case. A date in January 2006 worked for Gumbleton. The hearing would be in Ohio.

“My testimony made the points on why we need to make this change,” he said at the Call to Action conference session Nov. 4. “I also, I thought about this, and thought maybe the most persuasive thing I can tell you people is that I’m a victim.”

He couldn’t talk about that for more than 50 years, he said. “There was one time [after 2002] and I almost got up at the bishop’s meeting to tell my own story and to try to convince the bishops that we had to approach this whole thing differently. But I had my hand up but I didn’t get recognized right away and pretty soon that session was over. So I never did it at the bishops’ meeting. But this time I wrote it into my testimony.”

After giving his testimony in Ohio, the bishops in Ohio reacted so quickly, Gumbleton said, that they must have called the papal nuncio that night.

“And here’s the thing that’s strange: By that time, I’m a bishop already — 30 years at least — and I know all these people. And I’ve met with them many times — you know, the regional meetings, the national meetings. Not one of them called me up to talk to me about it. Now if they were angry they could call me up and holler at me, scream at me if they wanted. Or [ask] ‘why did you do it?’ Not one. And not one bishop across the whole country ever said a word to me about it in any kind of personal way.

Within a matter of days Maida called him about a letter from the papal nuncio that he was to share with Gumbleton.

The bishops had contacted the Papal Nuncio, Gumbleton said, and the Nuncio had contacted Cardinal Giovanni Re from the Congregation for Bishops in Rome. A letter for Gumbleton came from the Nuncio to Maida and then was shared with Gumbleton.

He corresponded with the congregation in Rome before over various issues when he was a bishop, he said, and the correspondence always takes a long time. But in this case, everything happened within 10 days. Cardinal Giovanni Re of the Congregation for Bishops wrote a two and a half page letter outlining the canons of canon law Gumbleton had violated.

“I don’t remember what all they were because I wouldn’t even read the letter,” Gumbleton said. “In fact, Maida didn’t even give it to me at first. The main thing was I had broken a canon which they said I violated what in the canon is called the “communio episcaporum”: the communion of bishops.

“We’re all supposed to be together, think together, talk together, you know, one voice. You know, how can that be? You’re a church of human beings; you can’t be.” But because he had left the Detroit archdiocese and gone to another diocese to give testimony in support of something the bishops in that region were against, he had been in violation, he said.

“And so this was, from their point of view, a major crime that I had committed,” he said. “So they demanded that I resign immediately as bishop and also resign my parish where I had been a pastor.”

He didn’t have to be a pastor, but he wanted to be a pastor and “really loved being” at St. Leo, he said.

“I couldn’t understand why I had to resign as pastor,” he said. He had no problem resigning as bishop, he said (“Because this was 2006 and by canon law I should have already retired a whole year ago, but when my date came up to retire, I decided — I knew there was no chance, but I just thought ‘I’ll test this and see what happens'”).

He sent in his resignation letter, and “immediately, my resignation was accepted,” he said. But he didn’t want to resign as pastor.

“In the archdiocese of Detroit, we have a policy at age 70, every pastor will write a letter resigning from his parish but if he’s in good health and wants to continue to work” he can be appointed as a year-by-year administrator, he said.

Other priests and classmates Gumbleton knew had done this, he said.

“And that makes sense, because when you’re pastor, as I said before, it’s hard to remove a person even if the person has become senile and is not functioning well at all,” he said. “You can’t remove him. Rome will defend the pastor.”

But an administrator can be moved anytime. “So I wrote a letter in which I said I’m requesting to resign from St. Leo Parish but with the understanding that I would be appointed administrator on a year-by-year basis for as long as it’s feasible for me to be the pastor.”

Within a few days, Maida sent him a letter, he said, telling him that request was unacceptable and that he had to resign. Gumbleton went to talk with Maida, and Maida repeated what Re had written in the letter, that Gumbleton had to resign as bishop and from the parish.

“That astounded me, partly because what does Cardinal Re know what’s good for a parish in Detroit, who should or should not be pastor?” Gumbleton said. “And why would the archbishop accept Cardinal Re’s demands? I mean, after all, he’s the archbishop. ”

The archbishop (or the pope) is the only one who can assign or remove a pastor in his diocese. “A cardinal who’s the head of a congregation doesn’t have any kind of jurisdiction or authority like that at all,” Gumbleton said. “So why would Maida — well, it’s part of the whole club system with the cardinals: you’re not going to stand up against another cardinal. And so he would not appoint me as administrator, so I had to leave the parish.”

Within a few days, one of the auxiliary bishops went to Gumbleton’s home and told him he had to leave. He asked if he had a couple of weeks to make arrangements but was told no: he had to leave. When he talked to Cardinal Maida, he asked for time to prepare the people of the parish for the change.

Gumbleton said he saw a letter that stated he was resigning the day before it was to be handed to parishioners. “So Sunday morning I have to pass this out at church, that says I’m gone right now. Well that was a terrible shock to the people and to me.”

“As I looked at it, though, it was all so irrational, because I’m removed from the parish, I not allowed to say Mass there … I could say Mass any other place in the diocese. So it was really against the people.” He continued to say Mass in the diocese, do confirmations, and be engaged in the other activities he did, such as Pax Christi.

“Yet the one thing that seemed to me that I should have been allowed to do is continue be the pastor of the parish for the benefit of the people, because we have a shortage of priests and nobody’s ever been appointed there as pastor since,” he said. “That’s really hurtful especially to a small parish. So it seemed like it was just vindictive. It wasn’t helping anything and wasn’t appropriate for the people of the parish to be punished for what I had done.”

He apologized to the parishioners at St. Leo and they were understanding, he said. He has been back to St. Leo since to celebrate Mass.

Gumbleton was also told not to go into another diocese without getting explicit permission from the bishop of that diocese, he said. “And that was an attempt, I guess, to prohibit my public speaking.”

Once, he was to speak in a diocese for a major Catholic organization but had to cancel at the last minute, but his name was still on the flyer. He got a voicemail from the bishop of that diocese, saying “I don’t want you to ever come to this diocese for any reason ever” and Gumbleton was surprised at how angry he was, because he was not a bishop to which he had violated “communio episcaporum.”

“I really have a sense that they [the Vatican] weren’t trying to silence me giving presentations on other topics which I do quite frequently,” he said. “I think they really were all upset about this one issue and that’s because it really does” put the focus, in a sense, on “a very important part of the church, and that’s the ordained priests, bishops and popes. ”

With that restriction, Gumbleton said, “It doesn’t feel very pleasant to go into a diocese to speak and know the bishop of the diocese would rather you not be there. And yet I don’t let that inhibit me, so I find ways to speak throughout the country,” he said.

“I don’t have any great anger against the bishops, Gumbleton said. “I feel bad for our church basically. I just feel we’re missing an opportunity to be healed because we don’t want to look at the deep problems that exist. And sooner or later we’re going to be forced to do that.”

Complete Article HERE!

A Key To Understanding Catholic Moral Theology

Don’t miss my five-part series on Catholic Moral Theology.

- Part 1 — A Key To Understanding Catholic Moral Theology

- Part 2 — Sins Of The Flesh

- Part 3 — Sacred Cows

- Part 4 — Seismic Shift

- Part 5 — Make Up Your Mind!

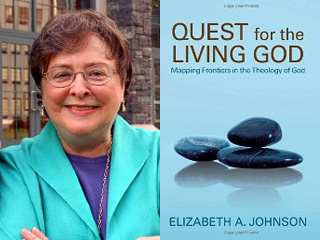

Bishops again blast nun’s popular book about God

The nation’s Catholic bishops again condemned a prominent nun’s book about God, in a move that may further fray relations between the hierarchy and Catholic theologians.

Given the popularity of Sister Elizabeth Johnson’s, “Quest for the Living God” in parishes and universities, the bishops’ renewed criticism may not help their, credibility in the pews, either.

The 11-page statement issued Friday (Oct. 28) by the bishops’ Committee on Doctrine reaffirms a March declaration that Johnson’s book “does not sufficiently ground itself in the Catholic theological tradition as its starting point.”

Johnson, a professor of systematic theology at Fordham University in New York and a member of the Congregation of St. Joseph religious order, published “Quest for the Living God” in 2007. It was widely hailed for elaborating new ways to think and speak about God within the framework of traditional Catholic beliefs and motifs.

In fact, “Quest for the Living God” became so popular that many Catholic universities began using it as a textbook, a development that sparked concern among conservatives, who have been gaining influence within the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops.

On Friday, Johnson said she read the bishops’ latest condemnation with “sadness” and “disappointment.”

“I want to make it absolutely clear that nothing in this book dissents from the church’s faith about God revealed in Jesus Christ through the Spirit,” Johnson said in a statement.

Johnson also said the bishops had not responded to her explanations and did not respond to her offer to meet with the doctrinal committee to discuss their differences.

A spokesperson for the bishops said Washington’s Cardinal Donald Wuerl, head of the doctrine committee, had offered to meet with Johnson.

The 21-page critique that the nine bishops on the doctrinal committee released last March puzzled many experts and observers because the criticisms did not seem to reflect the contents of Johnson’s book.

The bishops’ critique claimed that Johnson did not pay sufficient heed to Catholic traditions or did not argue hard enough on behalf of those traditions. The bishops also said that Johnson used ambiguous terms that were open to misinterpretation and could lead believers astray. Particularly, the bishops took issue with Johnson’s discussion of female images for God without giving sufficient weight to the primacy of male imagery.

The USCCB’s criticism irked Catholic theologians because it came without warning more than three years after the book was published and seemed to violate the bishops’ own guidelines, which call for dialogue with theologians rather than public pronouncements.

Those guidelines had been adopted in an effort to try to ease growing tensions between theologians and the hierarchy. Church officials said the popularity of Johnson’s book made it imperative that they act without wider consultations.

In addition, there were concerns because the top staffer at the doctrine committee, the Rev. Thomas Weinandy, is a conservative theologian who had long been associated with a controversial Catholic community in Washington.

In a May speech, Weinandy said that theologians can be a “curse and affliction upon the church.” He did not mention Johnson by name but blasted theologians who “often appear to possess little reverence for the mysteries of the faith as traditionally understood and presently professed within the church.”

In June, Johnson responded to the doctrinal committee with a 38-page defense of her work, arguing that the bishops had misunderstood and “misrepresented” her book.

The critique by the bishops does not mean that Johnson’s book is formally banned from parishes and universities, though it will likely become a marker for conservative critics if they see priests or theologians using the book in churches and classrooms.

And as often happens in these cases, the hierarchy’s disapproval has actually made the book even more popular than it was before.

In her statement Friday, Johnson said she received thousands of messages of support from readers after the condemnation was published in March, including one from an elderly Catholic man who had read “Quest for the Living God” in his parish book club.

“Now I am no longer afraid to meet my Maker,” the man told Johnson.

Complete Article HERE!