by Matt Assad

Within hours of getting a report in August that images of nude children were found on computers owned by the pastor of St. Ann’s Church in Emmaus, the Allentown Catholic Diocese informed authorities. But for the next six Sundays — even as Lehigh County investigators sifted through photos on two laptops — parishioners were urged at Mass to pray for their pastor’s health.

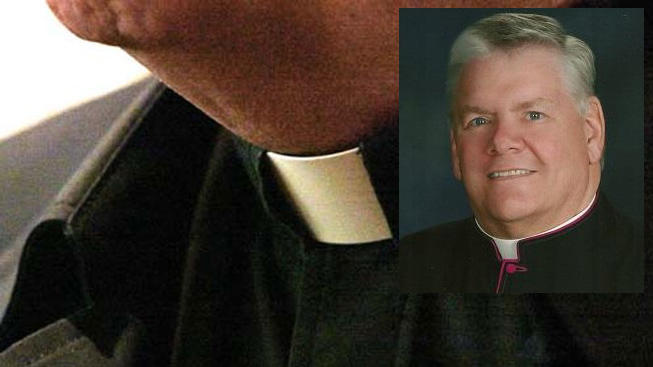

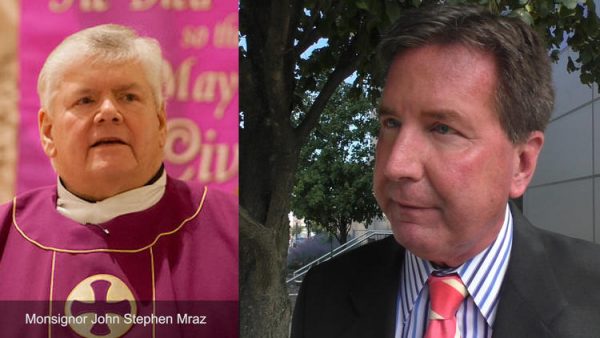

Monsignor John Stephen Mraz’s arrest Tuesday on charges of possessing child pornography left some members of his congregation angry that they would be asked to remember him in their prayers without being told he was under investigation.

“It just feels like a betrayal of trust, not only by Monsignor Mraz, but by the church,” Kara Sterner said. “I was married at that church and all three of my kids were baptized there. And now I don’t feel right. I just don’t have trust anymore.”

So shaken was Sterner that she held her 11-year-old son and 6-year-old daughter from religious prep classes at St. Ann on Wednesday, and she’s considering switching churches. She was among several parents who held their children from prep that night and among many who called the diocese and church office to voice their unhappiness.

The Rev. Dominic Pham, who lived with Mraz and got him to the hospital before the monsignor went to convalesce at Holy Family Villa in Bethlehem, has been fielding many of those calls. And he has a surprisingly simple answer for why, as he urged parishioners to visit Mraz in his recovery, he never told them their pastor was being investigated for child porn.

“I didn’t know. I knew he was very ill with diabetes and kidney failure, but no one told us about this,” Pham said. “I had no idea. They called us together the morning he was arrested.”

That St. Ann parishioners and staff remained unaware their pastor was under investigation for child sex crimes raises questions of whether the diocese is keeping its promise to be more transparent in the wake of the Catholic Church child sex scandal ignited by a Boston Globe investigation in 2002.

During Mass at St. Ann’s on Saturday evening, Allentown Bishop John O. Barres told parishioners that when Mraz left the parish this summer to undergo medical treatment, the events that led to his charges were unknown to anyone in the diocese. He said he understood that many were concerned about being kept in the dark, but that diocesan officials were being careful to cooperate with authorities and not interfere with the investigation.

“What happened is not a reflection of you or this parish or the school,” said Barres, who intends to address the parishioners at Sunday Masses as well. “St. Ann’s parish and St. Ann’s school are the same wonderful, valuable holy institutions that they were a week ago.”

Mraz’s arrest came more than six weeks after he asked a friend and parishioner on July 25 to perform maintenance updates on a laptop computer. According to the criminal complaint, the friend found nude images of boys in the computer’s recycling bin but didn’t come forward until Aug. 1 or 2, after he discovered a file named “naked little boys” on a second computer Mraz asked him to update.

Feeling “uncomfortable,” the friend reported what he saw to the diocese. Spokesman Matt Kerr said the diocese reported the accusation within a day to Lehigh County Children & Youth Services and the state Welfare Department’s ChildLine. A letter from diocese attorney Joseph A. Zator arrived in Lehigh County District Attorney Jim Martin‘s office Aug. 12, according to the criminal complaint. By Aug. 18, county detectives were serving a warrant to confiscate all of Mraz’s electronic devices, including the computers, the complaint stated.

At that point, a credible allegation had been established and for many dioceses across the nation, the policy would be to suspend the priest and tell parishioners why he was gone, said Michael Sean Winters, who writes the “Distinctly Catholic” column for the Washington D.C.-based National Catholic Reporter. That has become standard procedure, he said, in part because it could prompt parishioners who have had contact with the priest to come forward with information relevant to the investigation.

“They did the right thing by going to authorities immediately, but then once the allegation is determined to be credible, they have an obligation to tell parishioners that an investigation is underway,” Winters said. “It’s the way it is being done in model dioceses in places like Washington and Chicago and it’s been this way for a decade. You don’t wait until charges are filed.”

But that’s where Mraz’s case gets muddy. More than a week before his friend was reporting what he’d found on those laptops, Mraz had taken sick leave to deal with serious medical problems that included diabetes and kidney failure, Pham said. He’d collapsed at his residence and Pham called an ambulance to rush him to the hospital.

The diocese didn’t have to suspend him because he was already out of service and living at Holy Family Villa, a retirement home for priests, Kerr said.

Instead, the diocese turned the report to authorities and took a hands-off approach, Kerr said.

That left Pham in the position of stepping into the pulpit each Sunday to make an impassioned plea for people to pray and visit his ailing colleague.

The diocese was right to keep the accusation under wraps until charges were filed, Martin said.

“Are you suggesting they should have told people an investigation was going on?” he said. “That’s ridiculous. Absolute nonsense.”

Juliann Bortz, Lehigh Valley coordinator of the Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests, doesn’t see it that way.

She said Mraz’s arrest was an opportunity for the Allentown Diocese to prove that it has learned from the past. Instead, she said, it allowed Pham to unknowingly trot out the “health issues” excuse that dioceses around the nation have used over the decades to protect priests and keep allegations from the public.

“The way they handled this is still deceptive. It just gives you the impression that they wouldn’t have come forward if they thought they could hide it,” Bortz said. “It’s terrible for people to feel that way about their church. The only way they’re going to win back that trust is if they’re completely transparent. Unfortunately, they weren’t and we’re left to wonder.”

For Bortz, the issue of trust has always been at the heart of the sex abuse scandal. It was only inflamed again in March when a Pennsylvania grand jury report accused two Catholic bishops of allowing at least 50 priests and other religious leaders to sexually abuse hundreds of children for five decades in the Diocese of Altoona-Johnstown.

Based on the grand jury report, the attorney general’s office on March 15 charged three Franciscan friars with child endangerment and criminal conspiracy. The agency also set up a tip line for people to call the agency with abuse and cover-up allegations involving diocesan officials, and announced that it would be expanding its grand jury investigation into other dioceses across the state.

On Thursday, The Morning Call reported that the Allentown and Harrisburg dioceses are among those being investigated by a new grand jury in Pittsburgh, according to state Rep. Mark Rozzi, D-Berks, an abuse victim who said he recently testified before the panel in Pittsburgh. Agents from the attorney general’s office recently interviewed at least two other victims from the Allentown Diocese, according to the victims, who did not want their identity disclosed.

On Friday, four more Catholic dioceses — Erie, Greensburg, Pittsburgh and Scranton — were added to the Pittsburgh grand jury investigation of clergy sex abuse and cover-up allegations.

Mraz, whose 41-year career includes stints as chaplain at Lehigh University and theology teacher at Central Catholic High School in Allentown before he arrived at St. Ann in 2008, was charged Tuesday with viewing and downloading child porn, which falls under the sexual abuse of children in the criminal code.

Mraz, 66, was released on $50,000 unsecured bond. His Allentown lawyer, John Waldron, said Mraz has told detectives he downloaded the images for sexual gratification.

“What he’s alleged to have done is illegal and very wrong, but there is no indication that he did anything inappropriate with a child,” Waldron said. “We expect to have him psychologically evaluated so that he can get treatment.”

The situation leaves St. Ann’s leaders to contend with the fact that some parishioners have lost trust in them. Pham said they’re fielding calls at the parish office for anyone who wants an explanation, and have made counselors available for students or parishioners who want help dealing with Mraz’s arrest.

“Some aren’t happy and some are just angry, period, that their priest is alleged to have done this,” Kerr said. “Some wish they had known about it before seeing it online.”

In some ways, knowing that Pham was kept in the dark is helping Sterner deal with it. Maybe her diocese wasn’t open with her, but Pham wasn’t part of that, she said.

“I’m not sure why,” she said, “but it makes a difference for me.”

Still, she’s debating whether to leave for neighboring St. Thomas More in Salisbury Township.

Pham will continue to step into the pulpit to ask people to pray.

“Pray for us all at St. Ann, pray for the monsignor and have faith in the Holy Father,” he said. “It’s OK to be confused. Believe that Christ is with us and the answers will come in time.”

Complete Article HERE!