AND

The Fearful Fathers

Angry, isolated, paranoid and ageing, many of Ireland’s ‘ordinary’ Catholic priests feel failed and abandoned by the church hierarchy.

But where were the ‘good priests’ when they were needed?

THE VOICEMAIL was succinct. “Why don’t you, Mister Hoban, f**k off back to Rome with your nuncio . . . Piss off back to Rome, you f**ked-up celibates.”

“Keep away from my children, you bunch of perverts,” for example.

Fr Brendan Hoban transcribed these voicemails dutifully, along with other parish messages.

He reveals the wording after some reluctance.

His hesitancy is rooted in the same terror that has sent most priests deep into their parish bunkers this week, the terror of appearing to place the anguish of their own tattered, lonely souls above the suffering of the victims of clerical abuse.

So last week, when the Cloyne report was crashing into the public consciousness, Hoban, the 63-year-old parish priest of Ballina, Co Mayo, would have returned to the empty parochial house, heard the messages and told no one.

Then he would have repaired to his icy livingroom, where the sleeping bag on the armchair and the little plug-in radiator bear testament to the mean summer temperature of the ugly, soulless house he calls home.

Meanwhile, Enda Kenny was launching an unprecedented, historic attack on the Vatican in Dáil Éireann, accusing it of downplaying or “managing” the rape and torture of children “to uphold instead the primacy of the institution, its power, standing and ‘reputation’ ”.

Ireland, he declared, was not Rome but “a republic of laws . . . where the delinquency and arrogance of a particular version, of a particular kind of ‘morality’, will no longer be tolerated or ignored”.

Brendan Hoban wonders what all the fuss is about.

Enda Kenny was saying nothing that Irish priests haven’t been saying for years, he claims, about what the bishops should be doing.

“In effect, he is challenging Rome as distinct from the Irish church. We have no problem living in a democratic republic and I think we have shown ourselves, in the main, as people who have made a contribution to that republic . . . We have been waiting a long, long time for the bishops to say: ‘Let us run our own affairs, rather than tying our hands behind our backs . . .’ ”

“In effect, he is challenging Rome as distinct from the Irish church. We have no problem living in a democratic republic and I think we have shown ourselves, in the main, as people who have made a contribution to that republic . . . We have been waiting a long, long time for the bishops to say: ‘Let us run our own affairs, rather than tying our hands behind our backs . . .’ ”

But the Taoiseach’s statement does raise a concern, he adds.

“It’s that the Republic could become a cold place for Irish Catholics, as a result of an unnecessary confrontation between church and state. We fear that people would take from Enda Kenny’s statement that this is a dressing-down of priests and bishops, when it’s a dressing-down of Cloyne and Rome, and could be regarded as fodder for other agendas that might be coming up.”

Indeed, the Taoiseach was careful to address the anguish of the “good priests” in his statement: “This Roman clericalism must be devastating for good priests, some of them old, others struggling to keep their humanity, even their sanity, as they work so hard to be the keepers of the church’s light and goodness within their parishes, communities and the human heart.”

For them, their powerlessness has long been confirmed in the heedless appointment of bishops lacking the competence, intellect or independence of spirit to address the spiritual needs of a rapidly evolving republic; bishops such as Cloyne’s John Magee.

“He never worked in a parish, so had no experience of how to run a parish, never mind a diocese. I’m not blaming him for that – it’s back to who appointed him,” says Fr Billy O’Donovan, of Conna, in the Cloyne diocese.

It was Rome that handed the power to John Magee to appoint a head of child protection.

Magee chose Msgr Denis O’Callaghan, then in his late 70s.

Says another priest: “Denis O’Callaghan is an absent-minded professor – and they put him in charge of child protection?”

O’Callaghan is “a man with a great heart”, says Fr Hoban, “but completely disorganised”.

THERE IS CLEARLY a deep anger among ordinary priests.

This is reflected in the 550-plus membership of the fledgling Association of Catholic Priests.

But where were those angry, articulate voices when the damage was being done, when Rome was directing this republic’s affairs and their brothers in Christ were violating the young and vulnerable?

They were where they always were, says Hoban, “trying to do 1,001 things and trying to do them the best they can.”

So does that explain their silence?

There are two “difficulties”, Hoban says.

The first is the mistaken belief that a diocese is run by the bishop and the priests together.

“The fact is we are totally excluded from any say . . . Priests are effectively disenfranchised.”

The other difficulty is loyalty.

Priests live isolated lives.

“The dynamic of our ministry is that friends are very few and far between, but there is extraordinarily strong loyalty among the clergy,” Hoban says.

As well as that, “we were not people who would challenge the status quo. Those who would were weeded out in the seminary.”

Then there is the perennial problem of being “at the bishop’s mercy” in relation to transfers and advancement.

And thus the silence.

Does it all sound a bit self-serving?

“Yes, it’s fair to say that it was self-serving. That lack of moral courage.”

To illustrate this, he describes how a bishop and liturgists have been traversing the Irish dioceses, giving seminars to priests on the controversial new missal translations.

Despite the huge unease there was little or no reaction from audiences.

Then the bishop came to Knock, where he overran his speaking time, leaving no time for the pre-lunch question-and-answer session.

After lunch he launched straight into speaking mode again, whereupon one brave soul stood up and stated that a discussion was needed.

It sounds like the scene where Oliver Twist asks for more food.

Slowly, amazingly, the courageous priest was followed by several more.

“The liturgists were amazed because they presumed there was no opposition, as they hadn’t seen it before,” says Hoban.

Or maybe they hadn’t been reading the papers. It demonstrates what a cold place the church can be for a dissident, says Hoban.

“And we have reaped the whirlwind . . . If a good guy said anything , he said it to the bishop or the parish priest and felt that he’d done what was required. Guys find themselves in situations where their instinct says this doesn’t concern me. Because the message always was: go into your parish; diocesan policy is not your concern.”

In short, blinded by loyalty and conformism, priests trusted too much.

Now, pole-axed by fear, they are overcompensating.

Some have described their fellow clergy as “evil priests” in newspapers; one urges people to boycott the church collections.

The priests’ fear is no longer of the bishops; it’s of the head-spinning no-man’s-land where they now find themselves.

Ageing and isolated, they are operating in hostile territory where their Rome-appointed shepherds are themselves in a state of confused terror – “running around like 27 headless chickens”, according to Fr Tony Flannery – and where the Irish church’s straight-talking totem, Archbishop Diarmuid Martin, has effectively alienated them all.

The isolation and exclusion, compounded by this alienation from their bishops, explains much of the sense of abandonment and fear felt by many priests.

“The feeling is that in their lifetime there will be no end to this,” says Hoban. “For 10 years they’re blue in the face going to courses, seminars, studying guidelines . . . You could call it a high state of paranoia. Then, after all that, something happens in Cloyne and the bottom falls out of it.”

But the paranoia has also infected the priests’ day-to-day pastoral work.

“A woman comes to the door who may have psychiatric problems . . . What do I do? Take a chance by letting her into my front room? There is no doubt that priests have withdrawn, that they’ve become ultracareful and ultrasensitive on how they might be compromised.”

This is the raw terror of men who find themselves accused and deserted.

It’s another reason why so few are prepared to go public about anything.

“There is a phobia among them,” says Hoban. “It’s to do with the fear of accusations, especially ones that go back 30 years. It could be about exposure of an indiscretion from when he was a young priest. Or he could have a nervous disposition and have a phobia of false accusations being made.”

Privately, priests believe that some of those historic accusations are deeply suspect or

“shady”, as one put it.

“But you’re considered guilty from the word go,” say Fr Billy O’Donovan. “You almost have to prove your innocence.”

Accused priests have been publicly stood down, excised instantly from the diocesan directory, left with little or no income, ordered to vacate the parish house in days.

It depends entirely on individual bishops.

“There can’t be a priest in this country who doesn’t think the HSE and the civil authorities shouldn’t be informed as a matter of course ,” says Fr B, a priest who was falsely accused, “but there is also a matter of natural justice.”

Others cite the case of Canon Niall Ahern, who in 2006 was falsely accused of an offence alleged to have occurred some 35 years earlier.

He was back in ministry within months, but not before he had been publicly stood down by his bishop, stigmatised and humiliated in numerous ways.

Even when he was restored to ministry he endured headlines such as “Slur Fr returns to pulpit”.

THE COMPLEXITY of the issue is highlighted by Fr Billy O’Donovan.

He was asked by the diocese to be the official support for the Cloyne priest who was the subject of Bishop Magee’s notorious contradictory letters, one to Rome and a completely different one for diocesan files.

O’Donovan and the accused priest had been friends and their families had been friends.

“But the complexity is that the complainant would also be known to my family,” O’Donovan says.

“The awkwardness would be that the complainant’s family would assume that I’d be on the priest’s side.”

Having vehemently protested his innocence to anyone who would listen, that priest ultimately pleaded guilty in court to indecency charges.

O’Donovan doesn’t comment on the effect of this on him personally, merely saying that he remains in the role of support person.

Another priest speaks to us on condition of anonymity. Fr B, ageing and in poor health, yearns for what he calls “an adult conversation” with senior church figures about his ordeal.

“I’m not looking for money or an apology. I want us to own what happened.”

But, as O’Donovan puts it, the problem is that “of course false allegations have been made, but far too many have been proved”.

Nonetheless, this issue crystallises the abyss that now divides many bishops from their priests. There is no trust of any kind.

“We have the feeling that a facade is being created, such as in the Eucharistic Congress and the new texts, a pretence that all the troubles are now being dealt with and that, from here on, the church will flourish,” says Hoban.

“We are not encouraging people to join us. We know it’s not going to solve any problems. In this diocese there will be eight priests left from an original 34 in 20 years’ time. There is no planning . . . The whole thing is imploding with no recognition of this.”

Many trace the current problems to the abandonment of the Vatican II vision of a church of the laity, with parish councils at the core.

“Mostly it hasn’t happened . . . So when abuse cases arose they were dealt with by clergy, not by mothers and fathers,” says Hoban.

Now the last of the so-called Vatican II priests are disappearing, and the few young men who are replacing them are universally perceived as fiercely traditional and conservative.

Over and over, my conversations with priests return to the calibre of church leaders.

This is why O’Donovan, even during Cloyne’s traumatic week, believes that there is a “far more important week ahead”, meaning the appointment of a new bishop.

“Names being mentioned or guessed at are all right wing, conservative and with a Rome background,” he says.

“We’ve been there before . . . My biggest fear – and it is a real fear – is that someone would be appointed that priests and people will find unacceptable, and that many, priests and people, will walk in that event. We’ve taken enough. We want someone who will talk to us and listen to us.”

Would Irish priests support a breakaway from Rome?

“No,” says Hoban. “What you’re talking about here is the nature of the church. We are deeply unhappy with the competency of the leadership and the drift of Rome. The consultation and transparency we talk about, well, it’s not going to happen in our lifetime. But, to live with yourself, you have to keep saying the things you’re saying. The Association of Catholic Priests is the last fling of the dice.”

Behind all this is the reality of a laity that is voting with its feet.

“That’s the other unspoken thing,” Hoban says. “Our ability to speak to their needs is problematic. We don’t have the ability or the connection to speak out of their world. And that’s the result of celibacy, formation and the loneliness of the ministry.”

Why do they stay? “I’m 63,” Hoban says. “What else do I know? If I was 40 I’d look at things differently. There is a sense now that you’re in it and you’re loyal to it and that you owe something to the people you’ve worked with.”

But he is under no illusion. “Age and oddity go hand in hand. And, as someone said, there’s no one odder than an odd priest. It’s also been said that there is no one deader than a dead priest. People get on with it . . . We’re just functionaries.

“Tomorrow, the reality is that I will do a funeral for a family who have lost a father. That is probably the biggest thing that has happened to them in their lives, and they will remember every detail of this day. And you will do your part to the best of your ability. And at the end of it you’ll be able to look back and say: ‘It matters; I made a difference.’ That’s what the good guys are at.”

Vatican denies ordering bishops’ silence

IN THE first sign of a reaction by the Vatican to the Cloyne report, its press officer has claimed the Holy See never instructed Irish bishops to withhold information on abuse cases.

Fr Federico Lombardi said that, instead, the Irish Catholic Bishops Conference was told at a meeting in Rosses Point, Sligo, in November 1998 that neither the Church nor its priests should impede the course of civil justice.

Fr Lombardi’s statement rejected criticism of the Congregation of the Clergy, which undermined the Irish Church’s framework child protection document in 1997 by advising that mandatory reporting of abuse allegation could be contrary to canon law.

The Cloyne report considered this intervention by the Vatican, in 1997, to be entirely unhelpful because it told the Irish bishops that the adoption of their framework document could be “highly embarrassing” for diocesan authorities.

Fr Lombardi’s statement, delivered through Vatican Radio, said that the Congregation of the Clergy was only ever told that the framework was a working document from a bishops’ committee and not the agreed position of the Episcopal Conference.

He said its response was not an invitation to disregard Irish civil law, because there was no law in place at the time to require mandatory reporting.

He also said that, in 1998, the prefect to the Congregation for the Clergy, Cardinal Castrillion Hoyos, told the meeting in Sligo that the Church should not stand in the way of criminal investigations.

Fr Lombardi said the criticism of the Vatican since the publication of the Cloyne report went beyond any comments Ms Justice Yvonne Murphy made in the document itself, which he said were more balanced.

However, the survivors’ group One in Four described Fr Lombardi’s intervention as “wholly inadequate”.

Its executive director, Maeve Lewis, said his statement was an attempt to deny the findings of the Cloyne report.

“Fr Lombardi’s response completely lacks substance and is part of the now familiar refusal by the Vatican to acknowledge that the culture of loyalty and secrecy which facilitated the sexual abuse of children extended far beyond the Irish Church and that it was supported by official Vatican policy,” she said.

“It is further evidence, if it were needed, that the Vatican’s claim to prioritise the safety of children is completely lacking in credibility.

“It underlines the importance for the Irish state to ensure that an unequivocal legal framework is in place to protect children and to punish those who withhold information or place children in danger,” said Ms Lewis.

Minister for Foreign Affairs Eamon Gilmore has already asked the papal nuncio in Ireland, Dr Giuseppe Leanza, to return to him with a full explanation on the comments made by the Vatican in 1997.

Fr Lombardi delivered his statement on Vatican Radio under the guise of a personal comment rather than an official one.

http://tinyurl.com/3m9ldz3

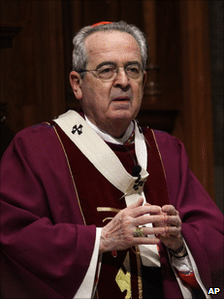

Philadelphia Cardinal Rigali resigns after abuse probe

The archbishop of the US city of Philadelphia has resigned, months after renewed accusations that the Catholic Church covered up child sex abuse.

Cardinal Justin Rigali had submitted his resignation in April 2010 upon turning 75, but Pope Benedict XVI did not act on it until now.

Archbishop Charles Chaput of the US city of Denver is to replace him.

US grand juries in 2005 and 2011 said the church protected abuser priests and left some in contact with children.

Time limits

Cardinal Rigali has been Philadelphia archbishop since 2003 and his retirement was expected this year, the Philadelphia Inquirer reported.

In 2005, a Philadelphia grand jury said Cardinal Rigali’s predecessor, Cardinal Joseph Bevilacqua, and his predecessor, Cardinal John Krol, knew priests were sexually abusing children but transferred the priests among parishes.

Time limits prevented that panel from bringing charges, however.

The archdiocese reacted by saying the grand jury’s report was “discriminatory” and “sensationalised” and accused investigators of “bullying” Cardinal Bevilacqua during his testimony sessions.

Cardinal Bevilacqua, however, repeated “my heartfelt and sincere apologies” to abuse victims.

Priests suspended

Then, in February 2011 a second grand jury report said at least 37 priests were kept in assignments that exposed them to children despite “substantial evidence of abuse”.

Cardinal Rigali responded by suspending more than 20 priests.

His successor, Cardinal Chaput, 66, is known as a staunch conservative and a vigorous opponent of abortion rights.

Last year he defended the decision by a Catholic school in Denver, Colorado to expel two children of a lesbian couple.

Clergy doing right thing is about timing not morality

Primate Sean Brady insists the long-awaited report into the mishandling of child sex abuse allegations by the diocese of Cloyne is “another dark day” in the history of the Irish Church. In this, as in so much else, he is entirely wrong. Any day on which light is cast on the obscure, murky workings of the Church is a day of illumination rather than darkness. That what it reveals is so utterly vile and contemptible is another matter altogether.

A previous such occasion, of course, was when Sean Brady’s own involvement in the cover-up of priestly perversion was revealed in 2009, when the faithful discovered how he had, 30 years earlier as part of an internal investigation into allegations against notorious paedophile Fr Brendan Smyth, made children sign oaths not to tell anyone that they had been abused.

Smyth, one of the most repulsive characters ever to wear priestly garb, went on to abuse dozens more innocents before being finally arrested; but even then, Primate Brady refused to take full responsibility by resigning, claiming that he was, in effect, only following orders, and that this was how things were back then. He also claimed that the current climate was a “totally different one to that of the past”.

It was a line echoed by Ian Elliott, CEO of the National Board for Safeguarding Children in the Catholic Church, who also said in 2009 that the progress towards better procedure had been “truly remarkable” and that there were now “champions for children” in place who wouldn’t let the same mistakes be made. “Remarkable” was bad enough, as if now allowing children not to be abused was some massive achievement, rather than the absolute minimum anyone could expect from those entrusted with their care; but it now turns out that these lauded champions weren’t up to the job either.

The report by Judge Yvonne Murphy shows conclusively that, as late as 2009, the diocese of Cloyne was still not following proper procedures on the reporting of sex abuse which the Church was supposed to have adopted 12 years earlier. In fact, they went further and deliberately misled the State about what they were doing. Despite the fact an internal church report in 2003 had found that Cloyne was putting children in danger by not following up allegations thoroughly, Bishop John Magee still told the late Brian Lenihan, then minister for children, that they were fully compliant, when they weren’t even bothering to make private enquiries as to whether accused priests had targeted other children.

And what is the response to all this? John Magee has vanished into the mist, maybe America, no one seems to know — which is to say that the Vatican surely knows, but they’re not saying either — and all that’s come from him is a statement, issued through a PR company in Dublin, Young Communications, containing the usual blether about how sad it all is. The Archbishop of Cashel and Emly, for his part, merely said it would be “helpful” if Magee came forward to answer allegations fully.

It makes a slap on the wrist look like the Spanish Inquisition in comparison, not to mention a mockery of the Vatican’s promise last year that “civil law concerning the reporting of crimes … should always be followed.”

Those at the head of an organisation set its moral tone. They are the ones to whom those beneath look for guidance on how to behave. Practically the entire hierarchy of the Church in Ireland is made up of people who, in one form or another, have made excuses for not doing the right thing. The context changes, but the excuses remain the same. If they can keep wriggling off the hook, why shouldn’t Bishop John Magee, or any of the others? The only reason why they should act differently now seems to be because people further up the chain are telling them that they should. But why should they listen to people who themselves have ignored the suffering of children when it would have been too difficult for them to do what was right? It’s like the IRA lecturing the dissidents on why they should stop blowing up policemen. Take away the political waffle and what it amounts to is: You shouldn’t do it anymore, even though we did when we were in your place, because it’s inconvenient now. It’s about timing, not morality.

Priests and bishops ought to listen, it could be said, because they’re bound by obedience to do whatever the Church tells them to do. They don’t have the right to refuse because to resist is to defy God. That only makes it all the more revealing that, 12 years after the Church apparently told them to comply with the law of the land, they were still prepared to ignore their own guidelines. It suggests they didn’t believe the hierarchy really meant it; that they were still detecting ambivalence; they were still getting a nod and a wink that what they were up to was not that serious. Indeed that’s what the report into the cesspit that was the diocese of Cloyne under Bishop Magee finds to be the case. Silence was officially sanctioned by the Vatican at the time when they were insisting publicly that all had changed, changed utterly, that a nice new Church had taken the place of the old one. Nor has anything said last week exactly reassured the sceptics, even now, that the Church quite “gets” what all the fuss is about. Instead, they’re still arguing the toss about whether abuse revealed in the confessional should be covered by the requirement to report crimes to the police. The Government has been bracingly unwavering about this; but that the hierarchy is still prepared to engage in theological point-scoring about sacredotal privilege, and to warn that the Government risks “antagonising relationships” if they insist that priests have the same obligation as every other Irish citizen to come forward when they know that children are being abused, is not only disappointing, but frightening. It seems to suggest that it’s not a National Board for Safeguarding Children in the Catholic Church that we need, but a National Board for Safeguarding Children from the Catholic Church.

They’ve had ample opportunities to set their own house in order. Too many, perhaps. They failed the test every time, preferring always to run away and hide behind lawyers and PR companies and each other, issuing one sophistical press release after another about the difficulties of doing the right thing, and meanwhile pumping out Lord Haw Haw-style propaganda suggesting that the institutions under attack are nowhere near as black as they’re painted. Well, that part’s true enough. They’re far blacker.