Penn State coaching legend Joe Paterno is out in the university’s burgeoning sex abuse scandal, and comparisons to the Roman Catholic Church’s own abuse scandals are in.

“The parallels are too striking to ignore. A suspected predator who exploits his position to take advantage of his young charges. The trusting colleagues who don’t want to believe it — and so don’t,” author Jonathan Mahler wrote in The New York Times.

“This was the dynamic that pervaded the Catholic clerical culture during its sexual abuse scandals, and it seems to have been no less pervasive at Penn State.”

The analogy is popular. But does it hold up to scrutiny? Yes, and no. Here are three ways in which the twin abuse scandals are similar, and three ways they are different.

SIMILARITIES

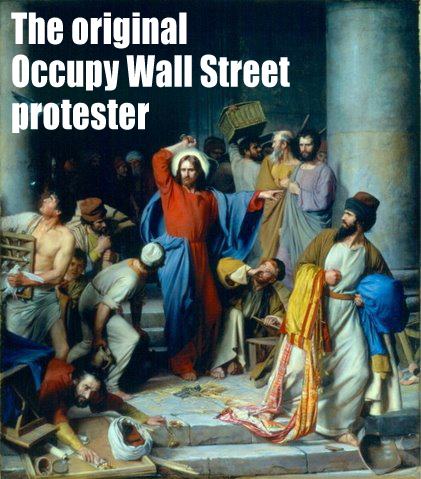

1. Sports is like a religion, with its rituals and incantations, rules and traditions, collective devotion and uniforms. Indeed, anthropologists say that like religion, athletic competition is one of the oldest communal impulses in human history, and today sports and religion mirror each other almost as much as they did in classical Greece.

To wit: a sign held by one Paterno supporter at a rally for the disgraced coach: “Two of my favorite ‘J’s’ in life: Jesus and Joe Pa.”

2. Whatever their bona fides as religions, Penn State and the Catholic Church are big, self-protective institutions. The cover-up is always as bad (or worse) as the crime, and Penn State leaders feared scandal — and probably harm to their own reputations — so much that they didn’t think about the welfare of the children. Same with so many bishops. And Boy Scout leaders. And teachers unions, and so on.

“The sort of instinct to protect the institution is very similar. And of course, in both cases, it backfires horribly. If your idea was to avoid a scandal, you sure failed,” Phil Lawler, a Catholic journalist in Boston, told The Associated Press.

That is why the public blamed bishops more than the predatory priests, and why so much anger has focused on Paterno rather than on alleged abuser Jerry Sandusky.

3. It took a grand jury to bring the Penn State abuse to light, just as it did (and continues to do) in the Catholic Church. Look at last month’s indictment of Bishop Robert Finn in Kansas City, Mo., for failing to report a priest suspected of child abuse, or the indictment last February of Monsignor William Lynn, a former top official in the Archdiocese of Philadelphia who is charged with covering up for abusive priests.

Institutions are not good at policing themselves. It is unclear how far the problem extends in college sports, and the church.

DIFFERENCES

1. Penn State has a system of accountability, however imperfect, because like any university, the school is governed by a board of trustees. In this case, the board took relatively swift action (albeit under severe pressure from the public and authorities) in part because if Penn State loses customers, it goes kaput.

The Catholic Church, meanwhile, believes that even the “gates of hell will not prevail” against it, and many church leaders embrace the “mustard seed” view of a smaller but more devout “saving remnant” that would be purified by suffering. In a reprise of the lesson of the Cross, they would “win by losing.” Needless to say, that’s not how universities, not to mention football teams, tend to see things. What’s more, the pope is answerable to no one — except God.

2. Sports is not an actual religion. Sports does not have divine sanction, nor can its leaders make use of divine symbols and power to exploit children — and potentially turn them against the eternal salvation that those leaders say is the point of a religion’s existence. That is a higher order of bad. Sports consists of games in the first instance, and the last.

If anything, sports is more like a cult — closed in on itself, exalting personalities more than a system or institution. Catholicism is actually a very decentralized community, and Catholics can hold their leaders in the same low regard that they have for politicians. That’s why you saw Catholics in Boston protesting to have Cardinal Bernard Law fired in 2002, while thousands of Penn State students rallied to let Paterno keep his job.

3. Penn State, and collegiate athletics as a whole, have not done as much as the Catholic Church to establish systematic safeguards for protecting children and educating students and staff about warning signs and best practices.

Of course, the Catholic Church has had a 10-year head start, and many safeguards were put in place after the fact. But sports experts note that there have been periodic sex scandals involving college coaches for years, and that bad behavior by college athletes — from sexual assault to bar brawls — is rampant. Yet there has been little focus on changing a culture that enables such behavior because college sports are, well, sacrosanct.

An ESPN investigation found that between 2002 and 2008, some 46 Penn State football players faced 163 criminal charges, and 27 players were convicted of or pleaded guilty to a combined 45 counts.

In the end, it may be the sensationalism of the sexual abuse of boys by men that has driven coverage of both the Penn State story and the Catholic crisis. And that may reveal as much about American attitudes as it does about the abuse itself.

Complete Article HERE!