By Laurie Goodstein and Sharon Otterman

As a young man studying to be a priest in the 1980s, Robert Ciolek was flattered when his brilliant, charismatic bishop in Metuchen, N.J., Theodore E. McCarrick, told him he was a shining star, cut out to study in Rome and rise high in the church.

Bishop McCarrick began inviting him on overnight trips, sometimes alone and sometimes with other young men training to be priests. There, the bishop would often assign Mr. Ciolek to share his room, which had only one bed. The two men would sometimes say night prayers together, before Bishop McCarrick would make a request — “come over here and rub my shoulders a little”— that extended into unwanted touching in bed.

Mr. Ciolek, who was in his early 20s at the time, said he felt unable to say no, in part because he had been sexually abused by a teacher in his Catholic high school, a trauma he had shared with the bishop.

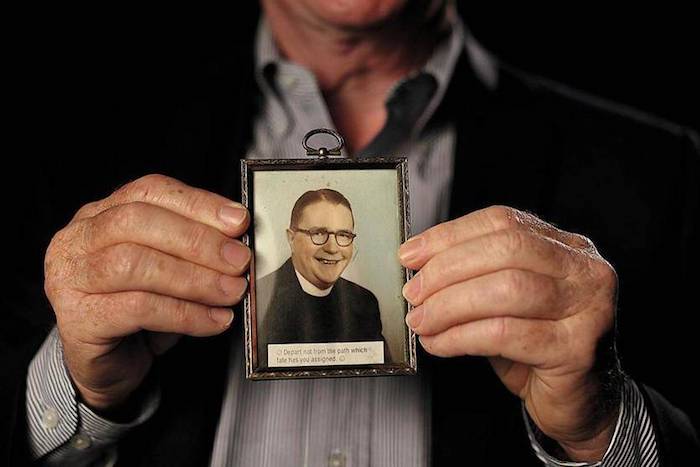

“I trusted him, I confided in him, I admired him,” Mr. Ciolek said in an interview this month, the first time he has spoken publicly about the abuse, which lasted for several years while Mr. Ciolek was a seminarian and later a priest. “I couldn’t imagine that he would have anything other than my best interests in mind.”

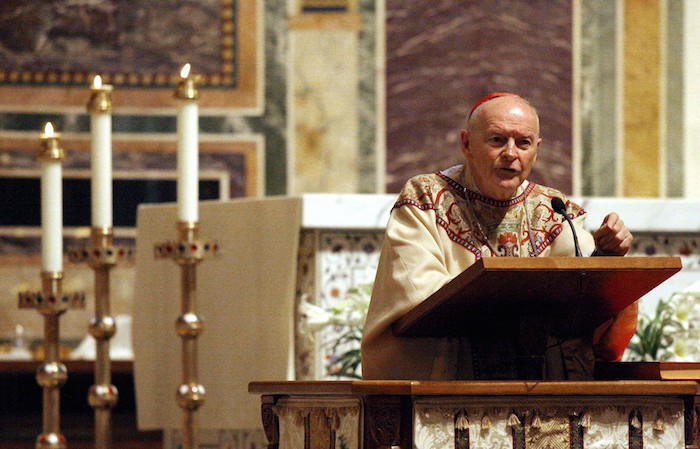

Bishop McCarrick went on to climb the ranks of the Roman Catholic hierarchy — from head of the small Diocese of Metuchen to archbishop of Newark and then archbishop of Washington, where he was made a cardinal. He remained into his 80s one of the most recognized American cardinals on the global stage, a Washington power broker who participated in funeral masses for political luminaries like Edward M. Kennedy, the longtime Massachusetts senator, and Beau Biden, the son of former Vice President Joseph R. Biden Jr.

Suddenly, last month, Cardinal McCarrick was removed from ministry, after the Archdiocese of New York deemed credible an accusation that he had molested a 16-year-old altar boy nearly 50 years ago.

Cardinal McCarrick, now 88, who declined to comment for this article, said in a statement last month that he had no recollection of the abuse. He is the highest-ranking Catholic official in the United States to be removed for sexual abuse of a minor.

But while the church responded quickly to the allegation that Cardinal McCarrick had abused a child, some church officials knew for decades that the cardinal had been accused of sexually harassing and inappropriately touching adults, according to interviews and documents obtained by The New York Times.

Between 1994 and 2008, multiple reports about the cardinal’s transgressions with adult seminary students were made to American bishops, the pope’s representative in Washington and, finally, Pope Benedict XVI. Two New Jersey dioceses secretly paid settlements, in 2005 and 2007, to two men, one of whom was Mr. Ciolek, for allegations against the archbishop. All the while, Cardinal McCarrick played a prominent role publicizing the church’s new zero-tolerance policy against abusing children.

The scandal of child sexual abuse by clergy has gripped the Catholic Church for nearly two decades, resulting in billions spent by the church on lawsuits, settlements and prevention programs. But while the church has made strides in dealing with sexual abuse of children, it has largely avoided a reckoning over sexual harassment and abuse suffered by adult seminarians and young priests at the hands of their superiors, including bishops.

Because bishops have control over priests’ assignments and complete loyalty is expected by the church’s clerical culture, seminarians and priests can be especially vulnerable to sexual harassment by their superiors.

“In the corporate world, there are ways to report misconduct,” Mr. Ciolek, 57, said at his home in New Jersey. “You have an H.R. contact, you have a legal department, or you have anonymous reporting, you have systems. Does the Catholic Church have that? How is a priest supposed to report abuse or wrong activity by his bishop? What is their stated vehicle for anyone to do that? I don’t think it exists.”

Now, after the fall of Cardinal McCarrick, some Catholics are saying that the church is on the verge of confronting its own #MeToo moment, akin to the wave of painful truth-telling that has swept through other workplaces, schools and Hollywood.

The Rev. Hans Zollner, a member of the Vatican’s commission for advising the pope on protecting minors, said that he has seen more victims come forward in recent months with accounts of sexual abuse in the church that they experienced as adults.

“The #MeToo movement has created a momentum,” he said. “It has brought another level of attention to this kind of hidden abuse.”

‘Uncle Ted’

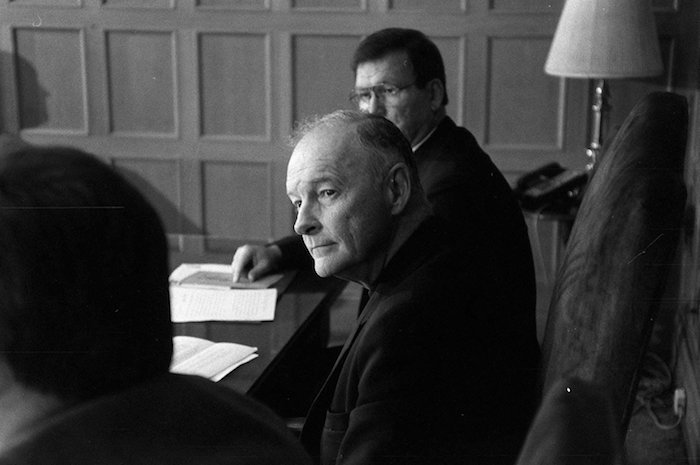

With his warm, gregarious presence, Cardinal McCarrick rose quickly through the ranks of the church after being ordained a priest in 1958. As a bishop, he took pride in his success at recruiting young men to the priesthood — including one he met in an airport, according to his colleagues.

In 1981, the New York-born clergyman was made the bishop of the newly created diocese of Metuchen in central New Jersey. The young men he recruited would attend seminary at Mount St. Mary’s in Maryland, before being ordained as priests for the diocese.

Those who interacted with him back then said he was friendly with all the seminarians, but would invite a few he especially favored to overnight stays at a beach house in Sea Girt, N.J. It was a small, simple house, some six blocks from the ocean — a retreat that the diocese had purchased at Bishop McCarrick’s request in 1984.

About four or five seminarians and young priests would go to the house at a time, usually on a Friday, where they would sometimes cook dinner or order pizza and socialize over beers, Mr. Ciolek recalled. Before lights out, Mr. Ciolek said, Bishop McCarrick would assign sleeping arrangements, directing one seminarian to share his room, which had one large bed.

Sometimes, Bishop McCarrick would start to rub a young man’s back as the rest of the group was filtering toward the bedrooms. Other times, it would happen once the young man who had been selected to room with the bishop was alone with him.

“My observations were that people were disgusted by it,” said Mr. Ciolek. “There were some who gloried in the attention it brought on them, even if it was screwed-up attention. But I don’t remember anyone welcoming it and hoping they would be touched.”

For Mr. Ciolek, there were about a dozen trips out of town with Bishop McCarrick, including to a fishing camp in Eldred, N.Y., with other seminarians, and once to Puerto Rico, where he waited in a hotel lobby while his host spoke with the local bishop. Bishop McCarrick also took him to Yankees games. At one game, Mr. Ciolek said he was seated in George Steinbrenner’s box between the team owner and Henry Kissinger, in what he described as one of the highlights of his young life. But after the games ended, Bishop McCarrick sometimes took him to a small apartment on an upper floor of a hospital that he used for overnight stays in the city, and directed Mr. Ciolek to share his bed.

Mr. Ciolek said that even though he just wanted to be a parish priest, Bishop McCarrick would frequently bring up how he ought to go to Rome and climb the church hierarchy.

With the harassment, Mr. Ciolek said, Bishop McCarrick seemed to have a line he would not cross with him. The touching would stay above the waist, avoiding the genitals, he said. There was no kissing, no holding hands.

But a second former priest, who received a settlement from the New Jersey dioceses for abuse by McCarrick, did not describe such a limit to the physical contact. This priest, who declined to be interviewed and whose file was provided on condition that his name not be used, was also a member of Bishop McCarrick’s select circle of seminarians.

By 1986, Bishop McCarrick had been promoted by Pope John Paul II to a much bigger job: Archbishop of Newark, one of the country’s largest dioceses with more than one million Catholics. In the summer of 1987, this former priest alleged, Archbishop McCarrick took him to an Italian restaurant in New York City, and then to the small apartment above the hospital. (Mr. Ciolek described the room in similar terms.)

There, Archbishop McCarrick asked the seminarian to change into a striped sailor shirt and a pair of shorts he had on hand, and joined him in the bed, according to the seminarian’s written account. “He put his arms around me and wrapped his legs between mine,” the account states.

He also wrote that he once saw Archbishop McCarrick having sex with a young priest in a cabin at the Eldred fishing camp, and that the archbishop invited him to be “next.”

In this former priest’s file were handwritten letters that the archbishop wrote to him when he was still a student, some signed “Uncle Ted,” and “Uncle T.” They sometimes addressed him as “nephew,” a term Mr. Ciolek said was used by the archbishop to refer to the young men he took on overnight trips.

One letter was written in 1987 while Archbishop McCarrick was aboard a plane in Poland on mission for the Vatican. “I just wanted to tell you how glad I am that we had the chance to get together this summer,” the archbishop wrote to the 26-year-old student. “It wasn’t as often as I would have liked but I know how ‘social’ my nephew is!”

Unstoppable Rise

Archbishop McCarrick’s trip to Poland was a sign of his growing prominence. His brother bishops in the United States elected him chairman of their committees on migration, international policy and aid for the church in Central and Eastern Europe. He met with Fidel Castro in 1988.

The first documented complaint about Cardinal McCarrick came at the latest by 1994, when the second priest wrote a letter to the new Bishop of Metuchen, Edward T. Hughes, saying that Archbishop McCarrick had inappropriately touched him and other seminarians in the 1980s, according to the documents.

The priest had a disturbing confession, the documents show. He told Bishop Hughes that he was coming forward because he believed the sexual and emotional abuse he endured from Archbishop McCarrick, as well as several other priests, had left him so traumatized that it triggered him to touch two 15-year-old boys inappropriately. The Metuchen diocese sent the priest to therapy, and then transferred him to another diocese. But Archbishop McCarrick’s stature remained intact; he was even given the honor of hosting John Paul II on a visit to Newark in 1995 and leading a large public Mass there for the pope.

Around 1999, Mr. Ciolek was called in by Archbishop McCarrick’s former secretary in Metuchen, Msgr. Michael J. Alliegro, who knew about the trips with seminarians, including the bed-sharing. He asked Mr. Ciolek, who had left the priesthood in 1988 to marry a woman, if he planned to sue the diocese, and then mentioned Archbishop McCarrick’s name. “And I literally laughed, and I said, no,” Mr. Ciolek said, adding that the monsignor responded with a sigh of relief.

In 2000, Pope John Paul II promoted Archbishop McCarrick to lead the Archdiocese of Washington D.C., one of the most prestigious posts in the Catholic Church in America. He was elevated to cardinal three months later.

At least one priest warned the Vatican against the appointment. The Rev. Boniface Ramsey said that when he was on the faculty at the Immaculate Conception Seminary at Seton Hall University in New Jersey from 1986 to 1996, he was told by seminarians about Archbishop McCarrick’s sexual abuse at the beach house. When Archbishop McCarrick was appointed to Washington, Father Ramsey spoke by phone with the pope’s representative in the nation’s capital, Archbishop Gabriel Montalvo, the papal nuncio, and at his encouragement sent a letter to the Vatican about Archbishop McCarrick’s history.

Father Ramsey, now a priest in New York City, said he never got a response.

Cardinal McCarrick’s ascent by that point seemed unstoppable, given his importance to the church. He was a prolific fund-raiser; as a founding member and president of the Papal Foundation, he rounded up deep-pocketed donors to pledge $1 million to the pope’s pet causes.

When Pope John Paul II made him Washington archbishop and a cardinal, the pope was in decline from Parkinson’s disease.

“He was not tracking these things closely because of his health, and his aides were not inclined to bring particular cases to his attention,” said John Thavis, a longtime Vatican correspondent and the author of “Vatican Diaries.”

Mr. Thavis pointed out that John Paul II also disregarded multiple warnings about a different, more notorious sexual predator, the Rev. Marcial Maciel, the founder of the Legion of Christ and another renowned church fund-raiser.

In 2002, when the turmoil in the church over the child sex abuse scandal was at a peak, Cardinal McCarrick was among the cardinals summoned by the pope to help manage the crisis.

Cardinal McCarrick voted in the papal conclave in 2005 that elected Pope Benedict XVI, and participated in the cardinals’ meetings in 2013 that led to the election of Pope Francis. He retired as leader of the Washington archdiocese in 2006 at 75, the standard retirement age for bishops.

A Reckoning

For many years, Mr. Ciolek, who became a lawyer after leaving the priesthood, told no one about his experiences. Then in 2004, after he began receiving counseling, he filed for a settlement from the church and received $80,000 from the Dioceses of Trenton, Metuchen and Newark.

Two years later, the church paid a settlement of $100,000 to the other priest alleging abuse. That priest had been forced to resign in 2004 under the church’s new zero-tolerance protocols against child abuse, based on his confession about touching two boys a decade earlier.

Father Ramsey said he continued to warn church leaders about Cardinal McCarrick. In 2008, he said, he raised the issue with Cardinal Edward Egan, the New York archbishop, but Cardinal Egan cut him off quickly. Father Ramsey said he was disturbed in 2015 to see Cardinal McCarrick serving at the funeral Mass for Cardinal Egan, so he wrote to Cardinal Seán O’Malley of Boston, who had been appointed by Pope Francis to lead a commission on sexual abuse of children.

“I have blown the whistle for 30 years without getting anywhere,” Father Ramsey said recently.

Cardinal O’Malley, through a spokesman, declined to comment.

Richard Sipe, a former priest who is an authority on clergy sex abuse, said that seminarians began to confide in him about the beach house sleepovers while he was a professor at Mount St. Mary’s Seminary in the 1980s. He said he wrote a letter to Pope Benedict in 2008, telling him the illicit trips to the shore home “had been widely known for several decades.”

One possible reason the allegations did not impede Cardinal McCarrick’s ascent is that unwanted touching of an adult by a bishop or superior is not explicitly stated as a crime under the church’s canon law, Catholic legal scholars said. There is a relevant canon (a legal provision), which says that anyone who abuses their “ecclesiastical power” and “harms somebody” is to be “punished with a just penalty.” But it was never applied to Cardinal McCarrick.

“He could have been removed from office — he certainly should not have been advanced,” said Msgr. Kenneth Lasch, a canon lawyer and retired priest in New Jersey who serves as a victims’ advocate.

The Vatican has removed bishops from their posts for having affairs with women and men; Cardinal Keith O’Brien, the leader of the church in Scotland, stepped down under Vatican pressure in 2013 after revelations of his sexual misconduct with seminarians and priests. But such punishments are rare, and are decided on a case-by-case basis by the Vatican.

In a statement to The New York Times, Cardinal Joseph W. Tobin of Newark said that he was “greatly disturbed by reports” that Cardinal McCarrick, his predecessor in Newark from 1986 to 2000, had “harassed seminarians and young clergy.”

“I recognize without any ambiguity that all people have a right to live, work and study in safe environments,” he wrote. “I intend to discuss this tragedy with the leadership of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops in order to articulate standards that will assure high standards of respect by bishops, priests and deacons for all adults.”

Many dioceses in the United States have their own policies on workplace sexual harassment. But there is no global policy in the Catholic Church on sexual harassment of adults, and no standard procedure for reporting sexual wrongdoing by one’s bishop locally, experts say.

The “Charter for the Protection of Children and Young People,” adopted by the American bishops at the height of the child sexual abuse scandal in 2002, does not cover victims older than 18. The bishops’ charter also contained no procedures for holding bishops accountable other than “fraternal correction” by fellow bishops. Cardinal McCarrick helped to draft the charter.

The Catholic Whistleblowers, a network of priests and nuns, recently sent a letter urging the American bishops to expand the category of victims to include adults, in particular those who are vulnerable to clergy sexual abuse because of overpowering intimidation by the abuser or because the victims are under the influence of drugs or alcohol. It also urges them to apply its zero-tolerance policy to bishops, said Father Lasch, a Whistleblowers member.

When Mr. Ciolek received his abuse settlement in 2005, it came with no formal admission of fault, and it barred him from ever speaking to the media about the abuse.

But since Cardinal McCarrick’s suspension, Cardinal Tobin, of Newark, and the bishop of Metuchen, James F. Checchio, have both apologized to Mr. Ciolek personally on behalf of the church. “I am sorry beyond words, and embarrassed beyond belief, at this atrocious conduct,” Bishop Checchio wrote to him. Mr. Ciolek has been released from his confidentiality agreements to permit him to speak publicly.

“If the church is genuine about cleaning up the rest of the mess, it ought to do something,” he said. “And that’s when I will judge the sincerity of the expressions of sorrow that I’m now receiving.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!