— and being shunned as a result

The text from Stephen Parisi’s fellow seminarian was ominous: Watch your back.

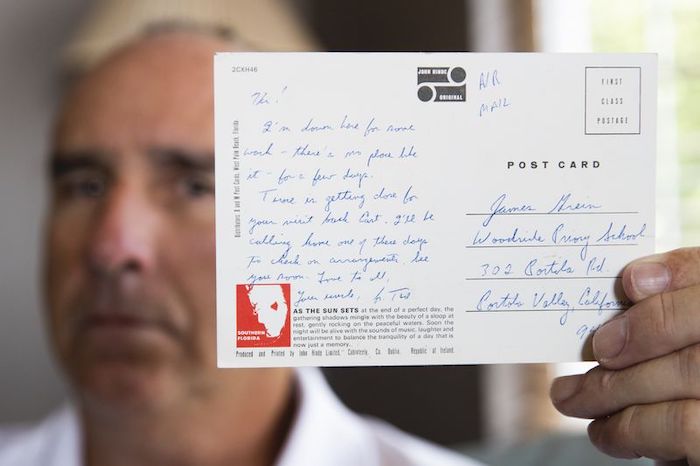

Parisi, dean of his class of seminarians in the Buffalo Diocese, and another classmate had gone to seminary officials about a recent party in a parish rectory. At the party in April, the men said, priests were directing obscene comments to the seminarians, discussing graphic photos and joking about professors allegedly swapping A’s for sex.

“I just wanted to be sure that you guys are protected and are watching your backs,” the seminarian’s text said. Authorities are “fishing to figure out who the nark [sic] is.”

Parisi and Matthew Bojanowski, who was academic chairman of the class, have made explosive news nationally recently after alleging that they were bullied by superiors, grilled by their academic dean under police-like interrogation and then shunned by many of their fellow seminarians after going public with sexual harassment complaints about those up the chain of command. The Vatican on Thursday announced it is investigating broad allegations church leaders have mishandled clergy abuse cases.

As striking as the charges is the fact that the men are speaking out at all. Parisi and Bojanowski — who both left seminary in August — are among a small but growing number of Catholic priests and seminarians who in the past year have gone to investigators, journalists and lawyers with complaints about their superiors. While still rare, such dissent has until now been nearly unheard of in a profession that requires vows of obedience to one’s bishop and offers no right to recourse, no independent human resources department.

Prompting the pushback, the men and experts on the U.S. church say, is what many Catholics view as the Catholic Church’s unwillingness to respond frankly and transparently to recently revealed cases of sexual mistreatment of seminarians and priests. That, and the #MeToo moment, in which Americans have shown new willingness to speak out against adult sexual abuse and harassment.

“My conscience bothered me. If it meant being thrown out, so be it,” said Parisi, now 45, who joined the seminary in 2018 after 25 years as a member of a Catholic religious order, caring for the sick and dying. He thought he knew the church well when he entered seminary. Now living with his parents and unemployed, he has received hate mail, and says priests in his hometown won’t acknowledge him. His faith in the institution has been “shattered,” he said. “That’s what you get for exposing the truth.”

In his Aug. 15 resignation letter, Parisi urged other seminarians, if they have issues, to go to state officials or journalists.

In addition to Buffalo, young men wrestling with scandals in Washington, D.C., and West Virginia, among other places, have also weighed expectations of obedience against their desire for more accountability — and chosen the latter.

More than half a dozen priests and former seminarians were the key whistleblowers in the recent fall of West Virginia Bishop Michael Bransfield, a well-connected fundraiser and donator in the U.S. church. Two recently exited West Virginia seminarians have gone public with allegations that Bransfield sexually mistreated them and have sued. One, who has not been named, said he was assaulted. The other, Vincent DeGeorge, 30, said Bransfield kissed and groped him, and pressured him to sleep over and watch porn.

“Because of the sex abuse crisis, I told myself going in [that] I wanted to be a priest, but I wasn’t going to let myself be complicit in a corrupt institution,” said DeGeorge, who left seminary last year after he says he was sexually harassed by his then-bishop, wrote an op-ed criticizing regional church leaders and quickly became a pariah.

“To scrutinize a bishop is to attack the church, is to be a bad Catholic,” DeGeorge said.

Several current and former clergy members spoke out beginning last summer about their treatment by defrocked cardinal Theodore McCarrick, some by name and others anonymously. The Washington Post has received more calls from Catholic seminarians and clergy members with tips and concerns in the past year than in the previous decade.

“I’ve never had conversations in all the previous years like the ones I’ve had in the past year. People feel they can finally talk about things” among themselves, said a seminarian in the D.C. region who spoke on the condition of anonymity because he fears dismissal.

Some said the expanding of a more aggressive Catholic media in the past couple of years has emboldened Catholics, including seminarians, to challenge the hierarchy.

A power imbalance

But even as the scandals have spurred some to speak out, church culture and theology dissuade more from raising their voices.

In the Catholic Church, bishops are kings of their dioceses, and priests swear an oath of loyalty to them. Seminarians’ pursuit of the priesthood rests completely with their superiors — the bishop in particular. There is no appeal or required explanation if one is deemed not to be priest material.

Some seminarians described having their spiritual fitness scrutinized if they raised too many questions. They fear that criticizing a bishop or higher-up could get them removed from seminary.

An internal church report investigating allegations against Bransfield quotes one priest-secretary who was allegedly harassed as saying he was in seminary when the bishop first asked him to remove his shirt.

“He stated that he did so out of fear. ‘Your life is at the will and pleasure of the bishop when you’re in seminary,’ ” the man told the lay investigators last year, according to the report, which The Post obtained.

In an email on May 7, 2018, a diocesan official in West Virginia told DeGeorge that he must stay over with Bransfield for a week — even though the then-seminarian did not want to.

“The request … was not actually a request. It was basically an expectation. You need to be there with the bishop during those dates,” the email reads.

The guide for seminarians by the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops encourages submissiveness.

“Seminaries should articulate that priestly obedience begins with humble and willing cooperation in seminary life, docility to direction and wholehearted compliance with the seminary’s policies,” it says.

Priests, seminarians and former seminarians described in interviews a climate of self-censure, with men often tattling on one another and gossiping rather than speaking openly. And when they do speak up, they said church authorities often do nothing.

They “say the right things, how we encourage honesty and openness, but deep down it’s clear they want to move on from [issues] as fast as possible,” said Mike Kelsey, who was a seminarian in the D.C. Archdiocese from last summer until January when students were openly upset that more hadn’t been done to learn what the past two archbishops — McCarrick and Donald Wuerl — did and knew regarding sexual misconduct.

Kelsey and other seminarians and priests interviewed for this article agreed that the problem lies in how the vows are interpreted and lived out within the church.

“I don’t think obedience is bad,” Kelsey said, noting that corporations also suffer from similar transparency problems. “But it’s also not something I’m signing up for if the hierarchy behaves in this way. If leadership and so many are not willing to get to basic levels of truth and justice, I’m not willing to sit there and obey them. I think the church is deeply corrupt and broken.”

Questions about how sexual misconduct in seminary is handled are considered so pressing that the University of Notre Dame last month released a first-of-its-kind study of 1500 seminarians on the topic. About 3,500 U.S. post-college men — who make up the vast majority of seminarians — were enrolled in programs in 2018-2019, according to Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate.

Seventeen percent said sexual abuse or misconduct is a problem at their schools, the survey found. Asked whether their administrators take the issue seriously, 84 percent said “very,” while 11 percent said somewhat or not at all. Of the 10 percent who said they have experienced, or may have experienced, sexual harassment, abuse or misconduct, 51 percent said they had not reported it. Of those who did, 42 percent said their reports were either “completely” taken seriously and acted upon or acted upon “for the most part.”

To get the seminarians to talk, researchers offered anonymity.

“They are afraid they’ll be judged as temporarily unfit, too assertive,” John Cavadini, director of Notre Dame’s McGrath Institute for Church Life, which crafted the new research, said about seminarians. “That’s one aspect of seminary education you wouldn’t have a close parallel of outside seminary. The bishop is a peculiar concentration of power in one person.”

The Rev. Carter Griffin, rector of the St. John Paul II Seminary in the D.C. Archdiocese, said that, if taught correctly, obedience to church authority can be a beautiful act, “to follow the Lord through the word of another.”

But younger men who grew up in the shadow of earlier abuse scandals know that automatically going “into protection mode” isn’t wise for the church, Griffin said. Regardless of what higher-ups do, he said, seminarians must do what’s right.

“ It might mean that people will misunderstand you, there may be consequences for your actions and you have to shoulder those,” he said.

Shunning as punishment

Speaking out, especially for those who do not leave seminary or the priesthood, can be risky. Some seminarians report a lack of support from their classmates — even social shunning.

An unnamed seminarian who filed a lawsuit against the West Virginia diocese earlier this year alleging that Bransfield sexually assaulted him declined to comment for this article. But his mother told The Post that many priests “whom he called friends and brothers” and many of his former fellow seminarians for the most part have kept their distance from him.

“They feel they have to choose the church,” she said. The Post isn’t naming her to protect the anonymity of her son. The Post doesn’t identify sexual assault victims without their permission.

The man and the Wheeling-Charleston Diocese reached an unspecified settlement over the summer.

DeGeorge’s allegation of sexual mistreatment by Bransfield became widely known recently when The Post reported it in a profile of William Lori, the Baltimore archbishop who led the investigation of Bransfield. He had already made waves for a seminarian — he was on leave — in December when he wrote a Baltimore Sun essay critical of Lori. Many priests and his former classmates still avoid him — or speak of him as a troublemaker, he said.

In a lawsuit filed Sept. 13 in Ohio County, DeGeorge alleges that Bransfield, the diocese and the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops did not rein in someone known as a harasser, leaving seminarians vulnerable.

In Buffalo, the priests whom Parisi and Bojanowski blew the whistle on were suspended for a few weeks and returned to ministry in June. Bishop Richard Malone issued a statement that seminarians who spoke out “are to be lauded for coming forward.” Malone is accused of mishandling of sexual abuse and misconduct cases.

After more than 20 years serving Catholic organizations, Parisi says he’s looking for work outside the church.

“There needs to be major reform … But in my view, that won’t happen. The system is a very well-oiled machine,” he said. The church hierarchy believes “it doesn’t need fixing in their view because it’s running exactly the way they want it to.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!