After a St. Cloud priest was recently released from prison after serving more than two years for sexual misconduct with an adult, one of his victims says the Catholic Diocese of St. Cloud needs to do more to ensure that he will never again serve in the priesthood.

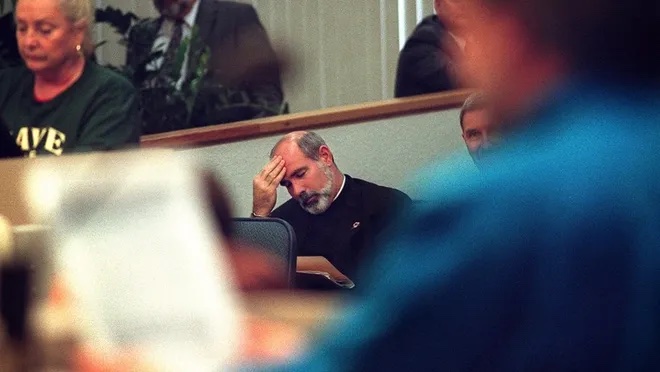

The Rev. Anthony Oelrich was released from the state prison in Lino Lakes on Oct. 17 after serving two-thirds of a 41-month sentence.

Oelrich pleaded guilty in 2019 to one felony count of third-degree criminal sexual conduct for being a member of the clergy and having ongoing sexual contact with a woman who’d come to him for spiritual advice. That’s prohibited under Minnesota law, and consent is not a defense.

The 56-year-old Oelrich remains a Catholic priest, although his priestly faculties have been suspended since his 2018 arrest. That means he can’t present himself as a priest, celebrate Mass publicly or wear the Roman collar.

In a statement, St. Cloud Bishop Donald Kettler said he continues to consider Oelrich’s future ministry status. Under church law, only the pope can decide whether he should be laicized, or dismissed from the priesthood.

In the meantime, Oelrich continues to receive his priest’s salary. He must pay for his own housing and other expenses. The church did not pay his legal fees during his criminal case, a diocese spokesperson said.

Before you keep reading, take a moment to donate to MPR News. Your financial support ensures that factual and trusted news and context remain accessible to all.

One person who’s been pushing the diocese for a clearer answer about Oelrich’s future in the church is one of his victims, a woman named Deborah. MPR News agreed to use only use her first name because she is a survivor of sexual abuse.

In an interview at her Twin Cities home last week, Deborah said the weeks leading up to Oelrich’s release have taken a toll on her health. She said she’s had trouble sleeping and suffered from migraine headaches because of the uncertainty about what the church is going to do about Oelrich.

Deborah said she was a young stay-at-home mom with five children trapped in an abusive marriage in 1993, when Oelrich manipulated her into a sexual relationship that lasted nearly a decade. She said he preyed on women like her in vulnerable situations.

“That’s one of the things so I had to read a lot and understand — how it is never consensual in that situation,” she said.

According to court documents filed in Deborah’s civil lawsuit against Oelrich and the St. Cloud diocese, her first husband complained to the diocese about Oelrich’s inappropriate behavior toward Deborah in 1994. The complaint says church officials did not support Deborah, but sided with Oelrich and blamed her.

“I was asked questions about if I had been fantasizing about him, if I knew the meaning of seduction, if I don’t know how to say no to people,” she said. “Everything was implied that I had seduced him. And yet, they never admitted any wrongdoing on his part.”

Deborah said the abuse by Oelrich continued, even after she divorced, remarried and moved to the Twin Cities. Eventually she sought support from the organization Survivors Network of Those Abused by Priests, or SNAP.

She filed a police report in 2016, but the statute of limitations for criminal charges had expired. Deborah did provide testimony in the criminal case against Oelrich for abusing a different woman, which led to his guilty plea.

MPR News also contacted the victim at the center of the criminal case, who declined to comment for this story.

Deborah said she met with Bishop Kettler in early June, and asked how the church would handle Oelrich once he was released from prison.

“We also told him in that meeting we’re concerned about the ongoing financial support that he would be given, because that comes out of the pockets of parishioners,” she said.

Deborah said the bishop told her he’d forwarded the investigation of Oelrich to Rome for a decision on whether the priest should be laicized.

It does bring her some comfort that Oelrich will remain under the supervision of the Minnesota Department of Corrections for 10 years.

Department spokesperson Nick Kimball said Oelrich must register as a predatory offender and follow special conditions, including refraining from employment as a clergy or minister without approval.

Deborah says she still thinks the diocese should provide more assurance that Oelrich will never again serve as a priest anywhere, in any capacity.

“Only because the law is going to be watching him and holding him accountable,” she said. “That is the only reason that the people are safe from him. The church is not providing any safety.”

Oelrich’s attorney, Paul Engh, provided a statement to MPR News saying his client served his time “with dignity and remorse.”

“He is being dismissed from the priesthood, and will not be contacting any witness from his case,” Engh stated.

Attorney Michael Bryant has represented many survivors of clergy abuse, including Deborah, in civil lawsuits against the Catholic church. He said internationally, the church has made progress on preventing clergy abuse, but there are still cases where it protects predatory priests.

Bryant said even though this case didn’t involve children, Oelrich still took advantage of his authority.

“It still goes back to preying upon vulnerable individuals,” Bryant said. “And so actions by the church that don’t protect vulnerable individuals seem contrary to all of their teachings.”

Deborah said she wants the St. Cloud bishop to be more transparent and address parishioners directly about Oelrich, as well as start a support group for abuse survivors.

“It’s very anxiety-producing that my church does not handle this well, that they’re not transparent, that we haven’t learned with everything that’s gone on,” she said.

In his statement about Oelrich’s release, Kettler apologized to the victims and all those who’ve been hurt by his actions.

“I am committed to fostering healing for those who have been wounded and doing all I can to end clergy abuse,” Kettler stated.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

‘Catholic Project’ study shows perception of the relationships between priests and bishops are at odds

By Rhina Guidos

A study of U.S. priests released Oct. 19 details clerics’ “crisis of trust” toward their bishops as well as fear that if they were falsely accused of abuse, prelates would immediately throw them “under the bus” and not help them clear their name.

The study “Well-being, Trust and Policy in a Time of Crisis” by The Catholic Project, written by Brandon Vaidyanathan, Christopher Jacobi and Chelsea Rae Kelly, of The Catholic University of America, paints a portrait of a majority of priests who feel abandoned by the men they are supposed to trust at the helm of their dioceses.

And while the study says priests overwhelmingly support measures to combat sex abuse and enhance child safety, the majority, 82%, also said they regularly fear being falsely accused. Were that to happen, they feel they would face a “de facto policy” of guilty until proven innocent.

The study, unveiled at The Catholic University of America in Washington, documents the environment between priests and their bishops in light of the “Charter for the Protection of Children and Young People” instituted in 2002 by the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops.

Commonly referred to as the Dallas Charter, it sets in place policy about how to proceed when allegations of sexual abuse of children by clergy or church personnel come to light.

“Indeed, many priests feel that the policies introduced since the Dallas Charter have depersonalized their relationship with their bishops; they see bishops more as CEOs, bureaucrats, and legalistic guardians of diocesan finances than as fathers and brothers,” the study points out and quotes a diocesan priest saying: “Our archbishop is a remote figure. Not at all personable. Not approachable. He appears to be a busy CEO and religious functionary.”

The document reveals that 40% of the priests who responded said they see the zero-tolerance policy as “too harsh” or “harsher than necessary,” adding that it’s too easy to lodge false claims of abuse against them. They feel bishops would not support a priest in the period necessary to prove his innocence.

“There’s this sense … that the bishops are against a priest who’s been accused, rather than doing what the bishop must do but still supporting the priest,” said one of the 100 priests that researchers interviewed in-depth.

“Most priests agree with the church’s response to the abuse crisis, but also fear that their bishops wouldn’t have their backs if they were falsely accused,” said Vaidyanathan, one of the study’s authors.

Of the 10,000 diocesan and religious priests surveyed, just 24% said they had confidence in U.S. bishops in general. Instead, priests in the study said they predominantly see the prelates as social climbers, careerists and administrators who barely know priests in their diocese by name.

“I don’t really trust most of the bishops, to be honest with you. I’ll show them all a great amount of respect. And if I was in their diocese, I would really serve them and try,” a priest told researchers. “But just looking across the United States and looking across a lot of bishops … I would say I have an overall negative opinion of bishops in the United States.

“They’re really not leaders or they’re just kind of chameleons … looking to climb up the ladder.”

The study says 131 bishops also participated in the study, which analyzed attitudes about priests’ well-being, trust and the policy related to the sex abuse crisis.

In response to the study, the USCCB’s Public Affairs Office released a statement by Bishop James F. Checchio of Metuchen, New Jersey, chairman of the organization’s Committee on Clergy, Consecrated Life and Vocations.

“I am grateful for the insight provided by this study which will assist the bishops in our ministry to our priests. While not surprised, I am heartened that the results report priests have such a high level of vocational fulfilment and that they remain positive about their priestly ministry,” Bishop Checchio said in the Oct. 19 statement.

The bishop referred to a figure in the document that showed that 77% of the priests in the study could be categorized as “flourishing” — saying they felt fulfilled and had a sense of meaning and purpose — and 4% reporting that they were thinking of leaving the priesthood.

“Our priests are generous and committed,” Bishop Checchio continued. “While acknowledging that circumstances will vary from diocese to diocese, the findings of this study are overall valuable in that they remind us of the importance of being always attentive to the care of our priests with the ever-growing stressors they experience in ministry, while we strive to address any issues that have damaged the unique relationship we enjoy.”

The study says that the “erosion of trust between a priest and his bishop” affects the level of well-being of a priest, and those with more trust fare better than others.

It also points out a great disparity of perception between the two groups, with bishops overwhelmingly seeing their role as more supportive of clerics. The majority of bishops surveyed said that they felt their role was akin to a brother, a father, a shepherd, a co-worker, when it came to dealing with priests.

Priests said strengthening relationships with bishops, having more social interaction with them, have the prelates know their names, communication, transparency about processes, as well accountability on prelates’ part would help alleviate the existing erosion of trust.

“The hope is that if we were to do the same survey five years from now, things would look different,” Stephen White, of The Catholic Project, said in a statement released before the presentation.

“Priests are happy in their vocations, but we also want them to feel less anxious and more supported. I know the bishops want that too. Hopefully this data can help in that regard,” he said.

Priests in the study also said they felt like cogs in the wheel, seen by bishops as liabilities. Some of the attitudes varied between diocesan priests and those who belong to a religious community, with those who were part of a religious order reporting more support.

The study also said that “at least some” of the mistrust comes from the way priests see “the application of policies created in the wake of the abuse crisis,” even as some bishops helped cover up abuses or were accused of being abusers themselves.

“Perhaps some bishops see themselves through rose-colored glasses,” a summary of the study said. “Or perhaps priests, in a beleaguered and prolonged state of stress and uncertainty, unfairly characterize their bishops through a lens of cynicism and fear. Or perhaps there is some truth to both perspectives.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Court documents reveal the names of more than 100 alleged residential school abusers

By Brittany Guyot

APTN Investigates has learned that 82 Catholic priests and nuns were named as alleged abusers in Manitoba residential schools.

A review of court documents detailed horrific physical and sexual abuses of Indigenous children in the federal residential school system.

The investigation uncovered 146 lawsuits that reveal the names of more than 100 alleged abusers from the Oblates of Mary Immaculate [OMI] and the Missionary Oblates Sisters, who staffed the schools.

The Catholic orders were put in charge of eight of 14 residential schools that operated in Manitoba. There were 139 residential schools opened nationally to assimilate thousands of Inuit, Métis and First Nations children.

The documents show the lawsuits were filed in the late 1990s and early 2000s, years before the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement [IRRSA] was finalized.

The majority of the lawsuits were abandoned the same year the settlement was finalized.

Mary Vanasse was sent to Sandy Bay Indian Residential School. She said the memories still haunt her.

“I think at first, I was really scared when I started seeing how the nuns were so abusive to the children,” she said.

Vanasse said it was common knowledge that children were being abused at Sandy Bay.

“The older girls were going around bugging the little girls, because I know it happened to me a couple times myself,” she said, “and somebody jumped in bed with me and tried to touch me and wanted me to touch them. And when I refused, she hit me.”

Vanasse isn’t surprised to hear how many alleged abusers walked the halls of her former school.

“I think there should have been some consequences,” she added, noting she feels the alleged abusers should have been criminally investigated.

Vanasse said her road to healing has been a long journey. She said spending time with her grandchildren and journaling have helped her along the way.

Later this year, she is set to publish a memoir about her residential school experience.

Rita Guimond is a survivor of the Fort Alexander Residential School that was located on Sagkeeng First Nation.

APTN Investigates identified a lawsuit she filed in 2004 against the Catholic church and the government of Canada.

“We were given different clothes to put on, and our clothes had numbers,” she said.

Guimond said her time at Fort Alexander was devastating. For years, it impacted her ability to show love to her own children, she added.

Court documents reveal the residential school housed more than 70 alleged abusers from the 1930s to the 1960s.

Including Fr. Arthur Massé, who was charged in June of this year with indecently assaulting a girl at the school.

Massé was accused of physical and sexual abuse in five separate lawsuits from 1998 to 2006.

Those lawsuits were abandoned in 2006 when IRSSA was finalized.

Massé is among dozens of Oblate priests accused of abuse, including Fr. Apollinaire Plamondon.

Residential school survivor Theodore Fontaine, who attended Fort Alexander Residential School, identified Plamondon as his alleged abuser in his memoir Broken Circle.

In an APTN News interview in 2014, Fontaine alleged Plamondon was a “sexual perpetrator.”

“Most of these people in this area, when they got their settlements under the residential school agreement, you’d say to them, ‘Man, you have a beautiful truck.’ They’d say, ‘Yeah, that’s my Plamondon car,’” Fontaine told APTN’s Cheryl McKenzie at the time.

APTN Investigates found Plamondon was named in 32 different lawsuits alleging physical and sexual abuse.

No criminal charges were ever laid against the now-deceased priest.

According to Fr. Ken Thorson, who speaks for OMI in Canada, Plamondon was referenced in 16 Independent Assessment Process [IAP] hearings. The hearings were held for survivors to testify about the abuse they suffered in support of their claims for compensation under IRSSA.

“The Oblates of Mary Immaculate are committed to full transparency about our role in Canada’s [Indian Residential Schools] system, including the operation of 48 schools [across Canada],” Thorson said in an email.

IRSSA was negotiated to address the harms caused by the schools. It awarded $1.9 billion to survivors, 26,000 of whom were put through IAP hearings to reveal serious physical and sexual abuses.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Former Dolphins chaplain Leo Armbrust accused of sex harassment

By Jane Musgrave

Leo Armbrust was never your typical Catholic priest.

Serving as chaplain to the Miami Dolphins, University of Miami Hurricanes and even briefly for the Dallas Cowboys, on weekends he was as likely to be seen pacing the sidelines shouting at trash-talking linemen as he was preaching the word of God to devout followers at Our Lady Queen of Apostles in Royal Palm Beach.

Known for his quick wit and a penchant for off-color jokes, Armbrust rubbed shoulders with famous athletes, business tycoons and community leaders. His well-placed connections helped him when he set off on a multi-million-dollar fund-raising odyssey to establish a Father Flanagan-style village for troubled and neglected teens.

However, 15 years after he founded Vita Nova, a less ambitious, but well-respected agency that provides housing and other assistance to hundreds of young adults no longer eligible for foster care, Armbrust is being accused of all manner of wrongdoing.

In a lawsuit filed this month in Palm Beach County Circuit Court, a former Vita Nova board member claims Armbrust, who left the priesthood in 2009, used agency accounts as his personal piggybank to fund a lavish lifestyle. In her lawsuit, Barbara McMillin accuses Armbrust, 63, of spending his days at the office trolling the Internet for sexual partners.

Further, she says, he harassed employees with crude behavior, obscene photos and anti-Semitic jokes. In at least one case, she says in her lawsuit, the agency was forced to pay a worker $200,000 to settle a sexual harassment complaint.

Her claims are salacious, provoking strong denials from agency officials and Armbrust supporters. However, the Wellington woman didn’t merely lay out her claims and leave it at that.

As part of her lawsuit, she attached confidential reports and internal memos that appear to shore up at least some of her allegations. They reveal Armbrust’s relationship with a hip-hop musician as well as statements from top staff that he was undermining Vita Nova’s work. Further, she said, she plans to send the information to law enforcement officials in hopes they will investigate.

‘Obviously, not happy’

Attorney Jack Scarola, who is being sued along with Armbrust, Vita Nova and several others, scoffed at McMillin’s attack. He said McMillin is simply trying to get back at him and Armbrust for filing a lawsuit against her and other board members for attempting to boot the former priest out of the agency he founded. While the other board members in February agreed to settle the lawsuit, award Armbrust an undisclosed amount in back pay and give him his job back, McMillin refused. So, he said, the litigation against her will continue.

“She obviously is not happy about that circumstance and has responded in what appears to be a very irrational fashion by suing everyone in sight,” Scarola said.

Attorney Gerald Richman, who filed a different lawsuit against McMillin and other board members on Armbrust’s behalf, voiced similar views. “Barbara McMillin has been extremely antagonistic toward Leo,” he said. “It’s almost like a vendetta.”

McMillin, a former CEO of Kids Sanctuary who has worked for children’s service agencies for decades, said the lawsuits Richman and Scarola filed prompted her to do some serious soul-searching about what she witnessed during her five years on Vita Nova’s board.

While she signed onto the settlement of the lawsuit Richman filed, she became suspicious when she said her own attorney wouldn’t reveal the full terms of the agreement that was hashed out with Armbrust to resolve the suit Scarola filed. She said she was appalled by the idea of giving Armbrust $100,000 to $200,000 in back pay and allowing him to return to his job as agency fund-raiser when he had proved so inept at raising much-needed cash.

“They can call me a mean old lady or whatever they want to do,” the 67-year-old said. “I just wouldn’t have felt I had done what was necessary for the kids if I hadn’t thrown this out there.”

And throw out she did.

As part of the lawsuit, she released an investigation the law firm Akerman Senterfitt did in 2012 in response to a grievance former employee Terry Sullivan filed against Armbrust.

In interviews with Akerman attorneys, Sullivan recounted the unprovoked tongue-lashings she received from Armbrust. He forced her to mend his clothes, wrap Christmas presents and go with him to pick out presents during the work day. On at least one occasion, she saw pornographic images on his computer, she told investigators.

When he began a relationship with hip-hop artist and rapper Jeancarlos Correa, who uses the stage name Remynd, Armbrust told her to prepare packages at agency expense to promote the struggling musician’s career, she said in the report.

In one instance, he asked her to order T shirts to promote Remynd’s album, “Sex and Computers.” Featuring a blow up doll with the word “Censored” stamped between its legs, the album cover image was so offensive to the printer that the agency used that it refused the order. Sullivan also told lawyers Armbrust once called her into the office to look at a sexually laced music video of Remynd, featuring the musician trying to bed a Sarah Palin look-alike.

“Ms. Sullivan said that the video did not make her uncomfortable. She stated that she ‘is not a prude,’” Ackerman lawyers wrote in their report. “However, she felt the video should not be shared in the office.”

Top brass at the agency agreed. Vita Nova CEO Jeff DeMario told lawyers that when he learned Armbrust was circulating the image from “Sex and Computers” among staff and officials from other nonprofits, he told him to stop. He also told Armbrust to stop asking Sullivan to do sewing for him.

DeMario said there were other lapses as well. He said Armbrust sometimes dressed inappropriately, such as wearing a T shirt with a photo of one of the cops from the 1970s TV show “Chips”and the words “Spread ‘em” on it. He said he had heard Armbrust make “inappropriate” jokes about black and Jewish people.

The real problem, DeMario said, was that there was little he or Irvine Nugent, another former priest who was then president of Vita Nova, could do to rein in Armbrust. While both were technically his bosses, as the founder, he had the upper hand.

“If this was anyone else, they would have been terminated,” DeMario told the lawyers. “We have an agency that is predicated on virtues and we are not practicing them in house. What kind of agency are we?”

Scarola said he hadn’t read the report that McMillin attached to the lawsuit. He said he advised Armbrust not to comment for this story. But he said the depiction of Armbrust as a bigot or a sexist is simply wrong.

“There is not an anti-Semitic bone in Leo Armbrust’s body — not the slightest hint of prejudice about anything,” Scarola said. As to those who might have found Armbrust’s jokes offensive, he said: “That’s more a reflection of their over-sensitivity rather than any impropriety on the part of Leo Armbrust.”

Armbrust’s natural exuberance and occasionally flamboyant behavior are part of his charm and the reason he is a successful fund-raiser, Scarola said. “He has excellent community connections with high-profile people,” he said. “He has established these connections with the force of his personality.”

However, there are questions about Armbrust’s fund-raising ability. Before Vita Nova board members agreed to settle the lawsuit Richman filed on Armbrust’s behalf, their attorney described Armbrust’s fund-raising as “abysmal.”

“As the director of development for (Vita Nova Foundation), Armbrust has performed poorly and has failed to bring in sufficient donations that would cover his high salary, his benefits and his assistant,” attorney Roy Fitzgerald wrote. “Since at least 2006, Armbrust has failed to meet the fund-raising budget, although the fund-raising budget was significantly lower than what should be expected.”

According to Fitzgerald’s short-lived counterclaim to Richman’s lawsuit, Armbrust earned $150,000 annually, plus benefits. An assistant made $60,000-a-year. According to industry standards, he should have been bringing in three or four times the $210,000 the agency was spending on his office, roughly $630,000 to $840,000 annually. Records show its investment portfolio declined from $15.7 million in 2006 to $6.2 million in 2013. The agency also gets government grants.

“Armbrust sets his own schedule and does not invest the necessary time and energy into fund-raising or into the organization to understand the programs the organization offers,” Fitzgerald continued. “As such, Armbrust has failed at getting the necessary fund-raising and could do more.”

Since that lawsuit was settled, Vita Nova board members and executives have changed their tunes. They dispute the allegations McMillin is making in her recently filed suit.

“Much of what Ms. McMillin alleges in her complaint is substantially inaccurate,” DeMario said in a statement. “As an organization, we are saddened that Ms. McMillin has taken a path that may harm the very organization that she was once affiliated with and may impact the hundreds of young adults we serve.”

McMillin said that isn’t her intention. She said the organization is a good one and praised DeMario as doing good work against enormous odds.

“I truly hope and I pray that people will support the organization,” she said. “They are doing a fabulous job for kids who need their support. But it just isn’t right to allow Leo to go on and give that man money that should go to the kids.”

Scarola said McMillin may pay a heavy price for her actions. By releasing confidential information she may have put Vita Nova at risk. “Clearly, she had a fiduciary responsibility as an officer of the corporation to preserve the confidence of the corporation,” he said.

McMillin said she’s not worried. “Protecting Leo is not part of my fiduciary responsibility,” she said.

Further, she said, she’s not done. After Easter, she said she plans to ask the Palm Beach County state attorney, Florida attorney general and the IRS to look at the records she has collected. Not all of them are in the lawsuit, she said. She said she has credit card receipts that prove Armbrust was using agency money as his own.

“I’m not trying to destroy the foundation. I am trying to save the foundation,” she said. “He has been looting it for years.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Vatican’s mishandling of high-profile abuse cases extends its foremost crisis

By Chico Harlan and Amanda Coletta

Three years ago, Pope Francis said the Catholic Church was committed to eradicating the “evil” of abuse. The pope and other church leaders drew up new guidelines to handle accusations. They pledged transparency. They said victims’ needs would come first.

“A change of mentality,” Francis called it.

But two recent major cases suggest that the church, for all its vows to improve, is still falling into familiar traps and extending its foremost crisis.

While the cases are markedly different — one involves a Canadian cardinal accused of inappropriately touching an intern; the other involves a Nobel-winning bishop from East Timor accused of abusing impoverished children — anti-abuse advocates say both instances reflect a pattern of secrecy and defensiveness. They say the church is still closing ranks to protect the reputations of powerful prelates.

In the case of the cardinal, Marc Ouellet, the Vatican did look into the accusations — but it delegated the investigation to a priest who knows him well, a fellow member of a small religious association. The priest determined there were no grounds to move forward — a conclusion the lawyer for the accuser says is dubious, given the possible conflict of interests.< Justin Wee, the lawyer, said Father Jacques Servais did interview his client in a 40-minute Zoom call, but rather than ascertaining the details of the allegations, appeared more interested in probing her motives and asking if she still believed in God.

“If the Vatican is handling cases like that, it means that if you’re powerful, nothing will happen,” Wee said. “No one should be above the rules.”

In the case of the bishop, Carlos Ximenes Belo, the Vatican disciplined him in 2020, one year after Holy See officials said they had became aware of accusations. But those restrictions — which included barring Belo from contact with minors — were kept secret by the church until a recently published Dutch news investigation that described abuse of multiple boys dating back to the 1980s.

Belo had attained stardom in the church by winning the 1996 Nobel Peace Prize for his work in seeking a peaceful resolution in East Timor’s long struggle for independence. But six years later, the Vatican announced he was stepping down — two decades before the usual retirement age — citing a canon law that refers to health or other “grave” reasons. The Vatican did not respond to a question about whether officials knew about abuse allegations at the time of Belo’s early retirement. He eventually wound up as an assistant parish priest in Mozambique. He said in a 2005 interview that his duties there included teaching children and leading youth retreats.

“Both cases are further indications that the whole accountability initiative is sputtering, is proving to be superficial and ineffective,” said Anne Barrett Doyle, the co-director of BishopAccountability.org, an abuse clearinghouse. “It makes you wonder: What has changed?”

The Vatican launched a drive to regain credibility against abuse after a wave of accusations not just against parish priests, but against bishops and cardinals — the power brokers of the church. Francis in 2018 called bishops to Rome for an unprecedented summit on abuse, which took place months later. And afterward, the church set out new rules and guidelines for how to handle cases, including instances when bishops are accused of coverup or abuse.

The church has shown progress on several counts. Dioceses around the world have set up reporting offices, giving alleged victims an easier way to alert the church of potential crimes. And in one instance, the church submitted itself to an act of unprecedented transparency, releasing a 449-page report into the abuse of defrocked American cardinal Theodore McCarrick, with revelations that bruised the reputation of Pope John Paul II.

But since then, the Vatican has not been transparent about any discipline against other prelates. And it has regularly ignored its own procedures, which provide specific instructions about who should be tasked to investigate bishops.

“It’s very frustrating, to be honest,” said one individual who has consulted with the Vatican on its handling of abuse, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to speak frankly. “When big names come out — the Vatican and the curia — the shield comes down. It’s incredible.”

Belo could not be reached for comment. The investigation by Dutch publication De Groene Amsterdammer included interviews with two adults who described abuse by Belo when they were teenagers, after which, they said, the bishop had given them money. The publication said the allegations against Belo had been known to aid workers and officials in the church. The Salesians of Don Bosco, a religious order to which Belo belonged, said in a statement it had learned about the accusations with “deep sadness and perplexity.”

The statement did not offer any timeline and referred further questions to those with “competence and knowledge.”

Ouellet, 78, has denied the accusations of inappropriate touching. He is widely regarded as one of the most important figures within the Roman Curia, the Vatican’s bureaucracy, as head of the department that oversees and vets bishops. Francis has allowed him to stay in the role well beyond the normal five-year term. He has a reputation as a moderate — a rarity in the ideologically divided church — and has served under several popes, including Francis, with whom he has near-weekly meetings.

The accusations against him surfaced publicly as part of a recent class-action lawsuit against the Archdiocese of Quebec, in which more than 100 people allege sexual misconduct against dozens of members of the Catholic clergy, lay and religious pastoral staff or volunteers. Many victims say they were minors at the time of alleged assaults.

The accusations date back to Ouellet’s time as archbishop of Quebec. A woman identified in the legal documents only as “F.” says that in the fall of 2008, when she was a 23-year-old intern, working as a pastoral agent at a diocese in Quebec, he forcefully massaged her shoulders at a dinner. When she turned around, the lawsuit alleges, she saw that it was Ouellet, who smiled and caressed her back before leaving.

In 2010, at the ordination of a colleague, F. alleges that Ouellet told her that he might as well hug her because there’s no harm “in treating oneself a bit.” He hugged her and slid his hand down her back to above her buttocks, according to the lawsuit. She says that she felt “chased” and that when she spoke to other people about her experiences, she was told that she wasn’t the only one to have that “problem” with him.

F. ended up trying to bring the case to light through official church channels, first to an independent advisory committee designed to receive church cases, and then — at the committee’s advice — in a letter to Francis himself. A month after her January 2021 letter to the pope, she was informed that Father Jacques Servais would investigate. She alleges that he appeared to have “little information and training” about sexual assault.

The Vatican did not respond to a question about why a close associate of Ouellet, who had known the cardinal since at least 1991, would have been tasked to conduct a preliminary probe. The church guidelines warn against a conflict of interests.

Wee, the alleged victim’s lawyer, said there was no follow-up from Servais or anyone else at the Vatican after the Zoom call in March 2021.

Servais did not respond to a request for comment.

Wee, who declined to make F. available for an interview, said she learned that the Vatican had determined there wasn’t enough evidence for a canonical investigation based on a Vatican news release after the allegations against Ouellet became public in August. He said she was not told privately beforehand.

Jean-Guy Nadeau, an emeritus professor of religious studies at the University of Montreal, lamented the lack of transparency in the case. He said Servais should have recused himself given the appearance of a conflict of interest.

“I don’t understand how that choice was made,” Nadeau said of Francis’s decision to appoint Servais to conduct the investigation. “I really don’t understand how such a choice could ever happen.”

Analysts said the case highlights the need for external investigators to probe misconduct allegations. David Deane, an associate professor of theology at the Atlantic School of Theology in Nova Scotia, said members of the clergy often close ranks and cannot be trusted to investigate one another.

“Having clergy handle the investigation is a real problem. It’s a real issue,” he said. “As long as that happens, it’s going to be very difficult to have both accountability and public confidence in the process.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!