By Geir Moulson

A report on decades of clergy sexual abuse in Germany that shone an unflattering spotlight on retired Pope Benedict XVI has added to already strong pressure there for the church to reconsider Catholic rules on issues including homosexuality and women’s roles, creating a mounting sense of impatience.

The latest flare-up of the sexual abuse scandal in the German church, one of the world’s richest, comes as a trailblazing reform process launched in 2019 in response to the abuse crisis begins to call for concrete changes.

The “Synodal Path,” which brings together Catholic bishops and lay representatives, approved at an assembly last week calls to allow blessings for same-sex couples, married priests and the ordination of women as deacons. It also called for church labor law to be revised so that gay employees don’t face the risk of being fired.

Many of those reform plans still need formal approval at future assemblies, but they put the German church on a potential collision course with the Vatican, whose approval would in most cases be needed to implement them.

The increasing pressures for reform coincides with a turbulent year in the German church. First came a furor over the conservative Cologne archbishop’s handling of reports on how church officials dealt with abuse cases, which led to Pope Francis granting him a “spiritual timeout.”

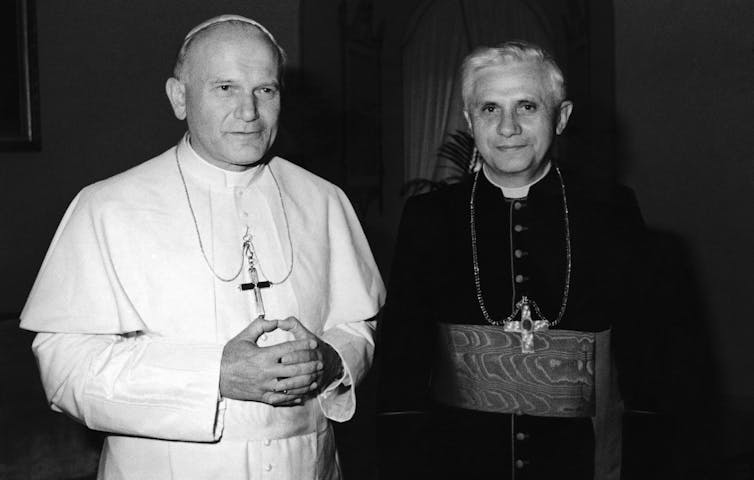

Then, last month, came a long-anticipated independent report commissioned by the Munich archdiocese into decades of abuse cases there. It faulted their handling by a string of church officials past and present, including Benedict, who as Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger was archbishop there from 1977 to 1982.

The German-born Benedict on Tuesday asked forgiveness for any “grievous faults” in his handling of clergy sex abuse cases, but denied any personal or specific wrongdoing.

Reform advocates and victim support groups criticized what they saw as a tone-deaf response that evaded responsibiity. The head of the German Bishops’ Conference, Limburg Bishop Georg Baetzing, put out a tight-lipped tweet saying Benedict “deserves respect” for having responded.

And the bishop of Essen, Franz-Josef Overbeck, told the Catholic newspaper Neues Ruhrwort that he fears Benedict’s statement won’t help abuse victims work through what happened to them.

Overbeck said he notes with concern that “people affected by sexual violence have reached with disappointment and in some cases also indignation to the former pope’s comments on his time as archbishop of Munich and Freising.”

The current Munich archbishop, Cardinal Reinhard Marx, welcomed Benedict’s response and again stressed that he himself takes the report “very seriously.”

Marx is a prominent reformist ally of Francis. A major thrust of his response to the report, in which he was faulted himself, has been to insist that the church needs “really deep renewal” to emerge from the abuse crisis.

Last week, Marx made his clearest call yet for loosening the celibacy requirement for priests, saying there is a “question mark” over “whether it should be taken as a basic precondition for every priest.” Another top European progressive, Jesuit Cardinal Jean Claude Hollerich, archbishop of Luxembourg and head of the commission of EU bishops conferences, called for changes in the Catholic Church’s position on homosexuality and priestly celibacy.

Meanwhile, the German Bishops’ Conference welcomed an initiative last month by 125 church employees who publicly outed themselves as queer, saying they want to “live openly without fear” in the church and pushing demands for reform.

At its weekend meeting, delegates to the “Synodal Path” strongly backed calls for a “change of culture” in church labor law, Baetzing said. They also called for the faithful to be given more of a say in choosing new bishops.

However, it’s unclear how many of the reforms proposed by the “Synodal Path,” whose next assembly is scheduled for Sept. 8-10, will become reality.

Sessions so far have pointed to a clear pro-reform majority, including among German bishops. But the process has sparked fierce resistance inside the church, primarily from conservatives opposed to opening any debate on hot-button issues.

It is being watched closely in Rome, where Francis has encouraged such “synodal” deliberations by national churches but has also sent out a strong warning to not go beyond established Catholic doctrine.

While progressives cheer calls for changes to church positions on celibacy and homosexuality, conservatives have voiced alarm that the German church is heading to schism, or a formal break from Rome. And while Francis has issued groundbreaking gestures of openness and welcome to gay Catholics, he has not altered the church’s teaching that homosexual acts are “intrinsically disordered.”

Francis also has dodged taking a stand on allowing married priests or on women deacons.

Phyllis Zagano of Hofstra University, who served on Francis’ first study commission on women deacons, cheered the German vote in favor of them and said the church as a whole needs them. The vote, she said, “comes at a time when the church continues to struggle against its history of abuse and its embedded clericalism, which combine to drive away women and their families.”

But the papal nuncio in Germany, Archbishop Nikola Eterovic, offered no encouragement to the synodal assembly in a statement that emphasized the importance of the broader global church, the German news agency dpa reported.

He noted that “the pope is, so to speak, the point of reference and the center of unity for over 1.3 billion Catholics worldwide, 22.6 million of whom live in Germany.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!