— The Archdiocese of Baltimore launched an investigation into Rev. Paschal Morlino after he admitted the payment to The Baltimore Banner

By Tim Prudente and Jessica Calefati

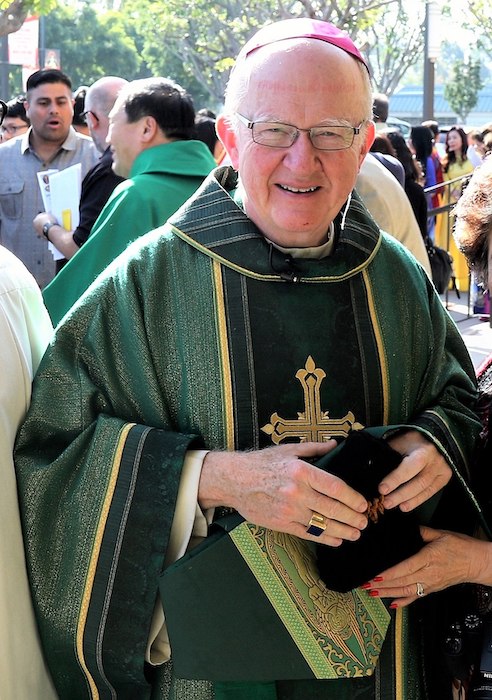

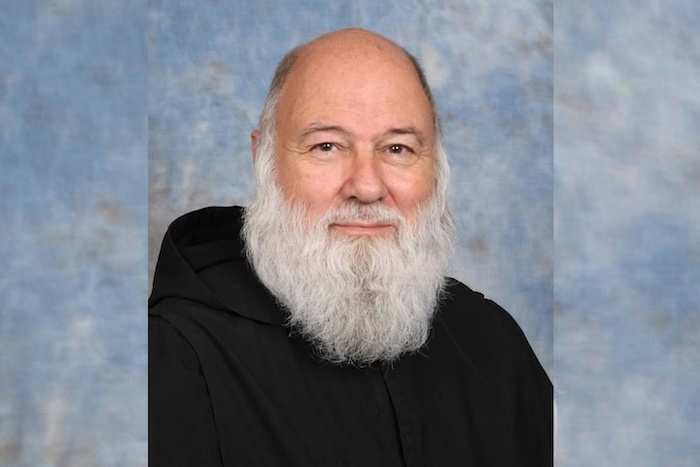

The Archdiocese of Baltimore has dismissed the Rev. Paschal Morlino, the celebrated “urban monk” of Southwest Baltimore who led St. Benedict Church for decades, following the recent disclosure that he paid $200,000 to quietly settle allegations of fraud and sexual assault.Morlino’s abrupt removal as pastor of St. Benedict’s was announced Saturday to parishioners, and it comes amid an investigation by The Baltimore Banner that brought details of the 2018 settlement payment to the attention of archdiocese officials.

“On Thursday when an inquiry was made by The Baltimore Banner, the Archdiocese of Baltimore and the Benedictines were first made aware of a settlement that had been entered into by Benedictine Fr. Paschal Morlino some years ago,” the archdiocese said in a statement. “The Archdiocese immediately engaged in an internal investigation and within 24 hours, a decision was made to remove Fr. Morlino as pastor of Saint Benedict Church.

“He is no longer permitted to celebrate Mass or engage in public ministry in the Archdiocese. Fr. Morlino has returned to his religious community, Saint Vincent Archabbey in Latrobe, Pa. The Archdiocese and Benedictines intend to conduct further investigation.”

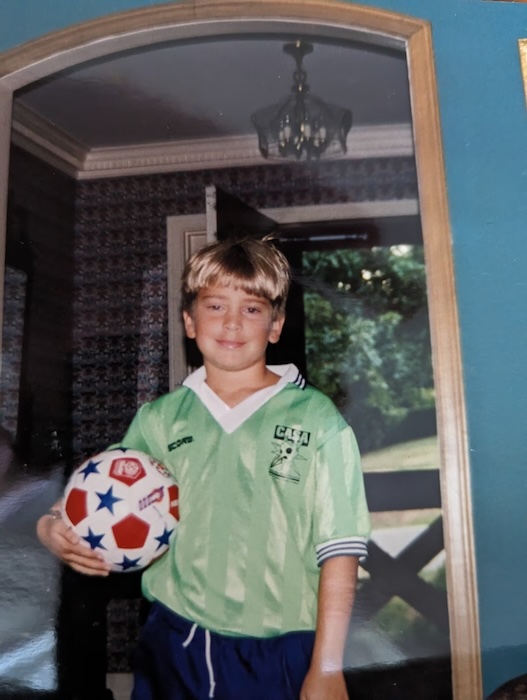

Morlino, 85, could not immediately be reached for comment.

The archdiocese’s decision to remove the popular Benedictine monk known as “Father Paschal” brings a stunning end to his 39 years as pastor of St. Benedict. Two days earlier, on Thursday, he granted a wide-ranging, 90-minute interview to The Banner at the church, declaring he had nothing to hide. Morlino confirmed that five years ago he paid $200,000 to the man who accused him of rape but denied that he had assaulted or defrauded the man.

“I just wanted to keep him quiet, to be rid of him, because he was just stirring up trouble,” Morlino said. “My conscience is clear; it’s all stuff that he made up.”

The man who accused Morlino died in April 2020. The Banner does not identify people who say they have been sexually assaulted without their consent.

Morlino has not been charged with a crime.

Morlino was ordained in 1966, and as a young monk outside Pittsburgh founded the Adelphoi house for boys. The nonprofit took in abused, neglected and delinquent youths. Adelphoi has since expanded to include 21 homes and serves 2,900 children and families a year, according to its website.

Around the historic St. Benedict Parish near Carroll Park, Morlino looms even larger. A self-described “Southern boy,” with his Virginia twang, he arrived in Baltimore during the 1980s like a whirlwind.

Morlino counseled sex workers, homeless people and people with addictions in some of the city’s poorest streets. He energized the congregation with his gritty, roll-up-your-sleeves evangelism. Under his leadership, the parish tripled in size, according to the church website. Congregants renamed the church’s block “Paschal’s Way.” They named the parish building the Paschal Center.

Former parishioner Kathy Durm-St. Amant said she used to adore the Benedictine monk like her own dad. But one day a friend told her a secret. The friend had vacationed with Morlino many years before on a cruise.

”He said he went on that cruise, he was in bed. He woke up with Paschal on top of him,” she said.

She encouraged her friend to call a lawyer. After he died in 2020, she found letters exchanged by the attorneys who negotiated his claim. She provided the letters to The Banner.

In one dated Jan. 24, 2018, her friend’s attorney, Joanne Suder, demanded $375,000 to prevent a lawsuit and accused Morlino of forging the man’s signature on bank records. The man had worked for Morlino, fundraising for the church, cooking, cleaning and carrying out errands.

“You stole all of his cash from checks telling him his expenses exceeded the balances of his checks,” Suder wrote.

Suder also accused Morlino of raping her adult client on the cruise in September 2000 and of multiple rapes in the years that followed.

Speaking about the man, Suder wrote, “His physician has opined that your sexual, physical, emotional and fraudulent behavior has caused him such injuries that he may never recover.” She declined to answer questions from The Banner about the matter.

Morlino told The Banner he went on a cruise with the man along with three other friends but he had no sexual contact with the man, either on the cruise or in the years after.

When asked about the alleged fraud, Morlino said the two had an agreement that the man’s paychecks would be deposited into a church account that paid for his health care.

“I took care of his medical insurance; that was the deal,” Morlino said. “He didn’t have any money; he played on my sympathy.”

The man was popular around Southwest Baltimore, Morlino said, and he saw him as an asset to the parish, someone who could help draw together the church and community.

His business dealings with the man went further than most others. Morlino said he paid the tax debt on the man’s home. But their yearslong acquaintance was tumultuous and ended when Morlino dismissed the man from his fundraising and other duties. Morlino said he was stunned to hear the man was accusing him of assault and fraud.

In response to the letter from Suder, the pastor made a counteroffer through his private attorney.

“Although Father Paschal is indeed not a rich person, in conjunction with his family and friends, he has managed to raise $25,000 to try and settle this matter,” wrote Salvatore Anello III, the pastor’s attorney. “There would have to be a release and total Confidentiality Agreement. As you can see whatever we do here, we are in an untenable position since the mere accusation, whether it be true or not, and it is not true, can end his ministry at St. Benedicts.”

Anello could not immediately be reached for comment Saturday. The sides settled in February 2018 for $200,000, according to documents reviewed by The Banner and confirmed by the pastor.

“It wasn’t true,” Morlino told The Banner of the allegations against him, “but how can you prove that in court?”

The man’s friend, Durm-St. Amant, was not bound by the nondisclosure terms.

She notified church leaders about sexual assault allegations involving Morlino in August 2018 using the archdiocese’s online portal, and said she later met with two church officials — Monsignor James Hannon, director of the division of clergy personnel, and Jerri Burkhardt, director of the office of child and youth protection. But she feels ignored today.

“What did he say? They’re going to meet with [Morlino] and counsel him?” Durm-St. Amant said, speaking about Hannon. “Not, ‘We’re going to shut him down.’ Not, ‘We’re going to take him out of service.’ That he needs counseling.”

Durm-St. Amant’s complaint alleged that a second man had been assaulted by Morlino on a different cruise. This man had died by 2018. Asked Saturday about its response to the complaint and allegations of two victims, the archdiocese addressed only the deceased man, saying Morlino denied assaulting this individual and that because the man was dead church officials could not corroborate the allegation.

Allegations against Morlino have not previously been disclosed. His name does not appear in the recent attorney general’s report on the history of sex abuse within the Archdiocese of Baltimore.

The 456-page report identified 158 priests accused of the “sexual abuse” and “physical torture” of more than 600 victims over the past 80 years. The findings led lawmakers to reform Maryland’s statute of limitations related to claims over old acts abuse.

The new law was expected to bring a flood of lawsuits against the archdiocese. On the eve of the Child Victims Act, the Archdiocese of Baltimore filed for bankruptcy.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!