By DEBBIE KELLEY

As Congress decided last week to codify federal protection of same-sex marriage, a high wall continues to divide the debate on religion and LGBTQ issues.

Some Christians consider same-sex relationships and gender fluidity to be sinful and contrary to biblical teachings.

Other Christians affirm LGBTQ distinctions and support same-sex unions and ordination of gay and transgender clergy.

The theological weeds are thorny.

While a 2019 Pew Research Center survey showed that 66% of religiously affiliated Americans thought “homosexuality should be accepted by society,” disputes over sexual orientation and gender identity have led to schisms among United Methodists, Anglicans and American Baptists.

Believers on both the conservative and liberal sides point to the other as despising one another, but one thing they agree on is that the dichotomy is a shame.

“It’s a major divisive issue, and it’s very unfortunate,” said Jeffrey Scholes, Ph.D., who heads the Center for Religious Diversity and Public Life at the University of Colorado at Colorado Springs, where he’s also an associate professor of religious studies.

The Nov. 19 shooting at Club Q, a LGBTQ+ bar, which left five people dead and 17 others injured by gunshot, has heightened the rift “much more profoundly than otherwise,” Scholes said.

There’s no question that a few biblical passages in the Old and New Testaments are “prescriptions against sexual acts of people of the same gender,” he said.

Jesus, however, never mentions a word about it, Scholes said.

Which leaves room for extensive and divergent biblical interpretation.

“It’s completely unclear what the Bible says about homosexuality,” Scholes said.

But the Bible is very clear to clergy like the Rev. Kelly Williams, founder and pastor of Vanguard Church in Colorado Springs, a congregation of the Southern Baptist Convention.

“We believe that the Bible teaches that homosexuality is a sin,” he said.

But it’s not THE sin.

“It’s really important that we not single it out as ‘This is worse than …’” Williams said. “Sin is sin.”

Jesus didn’t speak of many things in the New Testament, Williams said, including affirming a same-sex lifestyle or marriage, or saying whether people are born gay.

“We live in a world and a country where you can make a choice,” he said. “The need to make everyone agree with you is unhealthy. If you ask me the question, ‘Are people born gay?’ the answer is ‘I don’t know, the Bible doesn’t address it.’

“You cannot go to the Bible and find an answer to that question, so where the Bible is silent, we have to be silent.”

That same silence in the Bible leaves room for determining the meaning of text not just by words but also by who wrote it, when it was written and in what context, Scholes said.

“For people whose beliefs are set on a literal interpretation of the Bible, there is no such thing,” he said. “The Bible was written in Hebrew and Greek, and by the time we get it into English, there is no such thing as a literal meaning.”

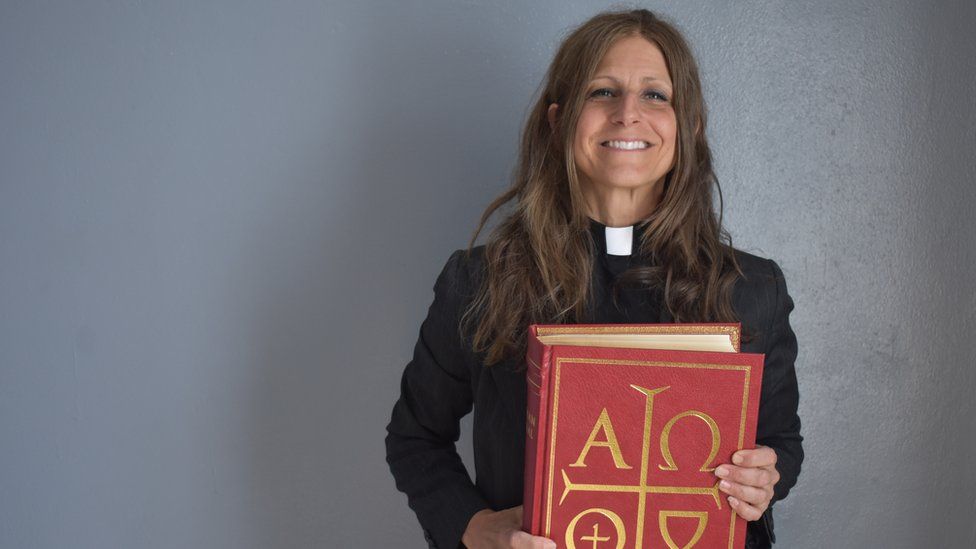

To clergy like the Rev. Dr. Joanne Sanders, a gay priest who’s assisting at St. Michael’s Episcopal Church in Colorado Springs, same-gender relationships are not a sin.

“I’ve been called to ministry to educate and teach from a critical theological perspective that counters some of the misguided theology that’s out there and causing serious harm to the LGBTQ+ community,” she said on a recent day in front of the memorial outside Club Q.

Progressive clergy have been taking shifts at the site to provide spiritual support and act as a watchdog, as they said there was concern that Christians who oppose LGBTQ+ people would harass memorial onlookers.

Protests at funerals, memorial sites and other locations around the nation have occurred in the past, including by such notorious groups as the Westboro Baptist Church from Topeka, Kan. The church has been labeled an official hate group for its vilification of not only gays and transgenders but also some religious denominations.

But that’s not how the majority of Christians treat LGBTQ+ people, say conservatives such as Jim Daly, president of Colorado Springs-based Focus on the Family, an evangelical Christian communications ministry.

“As a Christian leader in Colorado Springs, I’m never in a conversation that’s denigrating the LGBTQ community or the movements,” he said.

“Most Christians that I know and interact with, we’re big believers that everybody’s created in the image of God, and everybody’s due respect — even if we disagree,” Daly said.

Focus on the Family publicly opposes same-sex marriage, transgenderism and related issues and has offered “conversion therapy” to restore people to heterosexuality, a controversial practice.

“We’re Christian folks following Scripture that indicates how we should behave and treat people, how marriage is defined by God in our opinion,” Daly said. “When we express opinions in a constitutional republic, we feel we’ve done it with no ill will or meanness toward anyone.”

Scholes, the UCCS professor, disagrees.

“By challenging something so deep-seeded as sexual attraction and promoting gay conversion therapy, they may not say that’s hate, but what they’re saying is it’s wrong, and if it’s not hate, it comes across as animosity, and is at the very least a serious level of disrespect,” Scholes said.

Said Daly, “We’re the first to say we’re sinners and saved by grace. We’re trying to espouse what we believe as Christians, and it’s gotten to the point where you get beaten down for just expressing that.

“We’re the ones receiving the ridicule.”

Bible as a weapon

Sanders spent a significant amount of her life enmeshed in evangelical communities before she “was able to come out (as lesbian) and see myself in the image of God.”

During that process, the priest said, her faith deepened and became “more authentic and real.”

“One of the most heart-breaking things is how the Bible is used as a weapon,” Sanders said.

“It’s irresponsible to say, ‘love the sinner, hate the sin,’” she said. “What that says to me is a lack of willingness to go to a deeper place together as humanity and recognize what those kinds of things are doing to people, and how it’s so much the antithesis — if we really are willing to look honestly at the life of Jesus.”

Sanders said she’ll spend the rest of her life “working to be a voice and always being willing to be in conversation with others that may have a different point of view.”

Williams, the Southern Baptist pastor, said, he, too, is willing to speak with anyone who wants to talk. His church hosted community conversations following blowback against conservative Christians, who led a 1992 voter-approved constitutional amendment banning rights for gays, lesbians and bisexual people, which the U.S. Supreme Court overturned.

“I have no animosity or hard feelings toward the homosexual community,” he said. “I want our church to be in relationship with people who are wrestling with this issue; we want to create an environment where we add a name and a face so we can show love and respect to one another.”

Said Williams, “The Bible teaches the rejection of Jesus is what sends you to hell; it’s not sin.”

Everyone’s a sinner, said The Rev. Gary Darress, a deacon at St. Michael’s Episcopal Church, who also recently was offering support at the Club Q memorial.

He points to Jesus’ admonitions to his followers not to judge others, to examine one’s own sins before disparaging actions of others and to love your neighbor as yourself.

“So why are we as Christians pointing fingers at another person’s so-called sins?” he said. “In the Gospels, Christ met people where they were at. Jesus opened his heart to the Israelites, Gentiles, Romans, Samarians — why are we having such a hard time opening our hearts to the people who identify as LGBTQIA?”

Darress said he knows that people who criticize LGBTQ people may be scared by the way someone looks or acts or has an alternative lifestyle.

“But, why does it have to be, ‘You have to change, you’re acting differently from how God made you’? Do we really know how God made you? Why do we have to confine God to a box and say what God’s love is?”

‘Everybody’s on a journey’

In daily life, as LGBTQ people seek acceptance and understanding, some Christians struggle with inner spiritual conflict.

“We’re all in one way trying to wrestle through this painful and delicate issue because we do have loved ones we care about, whether friends or relatives, that identify as same-sex,” said Williams, the Southern Baptist pastor.

Gayle Rappold started an LGBTQ support group eight years ago at Holy Apostles Catholic Church and then moved it to her home. One year ago, it relocated to Sacred Heart Catholic Church under the name “Journey.”

“Because we know everybody’s on a journey with this,” the 82-year-old mother of five said.

A dozen or more parents and loved ones of LGBTQ people show up monthly, not to debate religious doctrine or beliefs but to share stories and lean on each other on what can be a difficult path to walk.

“There’s a conflict between our faith, when we’ve been taught homosexuality is wrong, it says so in the Scriptures, yet I love my child and don’t want to reject my child,” Rappold said. “There’s also a shock that comes when your child comes out and you don’t expect it.”

As per its mission, the group is a safe place, a nonjudgmental atmosphere where people bond and “primacy of conscience” is understood.

While Rappold, who has a gay son, is a practicing Catholic, a denomination that accepts LGBTQ+ people but does not allow for same-sex marriage and promotes chastity regarding same-sex attraction, she said her personal conscience dictates that she love and accept her gay child.

“And if that gay child falls in love and gets married, then I accept that,” she said. “I love and welcome gay people without questioning the life or lifestyle.”

Rappold said she does not speak for the Catholic Church.

The leader of the Roman Catholic Church, Pope Francis, has reaffirmed primacy of conscience, the belief that God reveals himself to followers while they navigate tough moral questions.

But some Catholics have criticized the Pope for doing so, and some bishops do not permit such groups as Journey under their leadership, Rappold said.

Rappold said she learned years ago not to try to change anyone’s opinion.

“My response is, ‘I’m sorry, but I feel differently than you do — I love my child and don’t judge my child,’” she said.

The Bible’s ‘consistent message’

Respect is part of what it’s going to take to bridge the disunity, religious leaders say.

“In this debate and discussion, I say don’t be so quick to villainize everybody who disagrees with you — you might find they have more compassion for you than those who agree with you,” said Williams, the Southern Baptist pastor.

Williams said while he doesn’t personally force his views on anyone, he can’t stop speaking about or change what he believes the Bible teaches, because then he wouldn’t be faithful to what he believes God has asked him to do.

“I know that I will be perceived because of my stance as hateful or unloving,” he said, “and all I can say to that is I’m trying to be faithful to my understanding of what Scripture teaches, and I’d love the opportunity to demonstrate love to anyone who disagrees with me.”

Love, the most-preached topic that appears throughout the Bible, is what potentially could bring both sides closer together, said Scholes, the UCCS professor.

“Loving one another is the consistent message that is always applauded in the biblical texts,” he said. “Jesus would be all in favor of two men or two women in love. There’s no question in my mind about that.”

Sometimes people change their minds, Scholes said, pointing to the family of former Vice President Dick Cheney, some of whom opposed same-sex marriage until the youngest daughter said she was a lesbian. Former President Barack Obama also was against gay marriage but then reversed course, Scholes noted.

Sanders, the lesbian Episcopalian priest, said willingness and humility must be employed for religious factions to come together.

“Stop causing the human pain and suffering that religion and people who speak in the name of Christianity in particularly hateful ways do, which is so destructive,” she said.

Fear of the body and of sexual relationships is “propelling so much of this hate speech,” Sanders said.

Both sides call for civility.

“It’s sad to think we can’t have different opinions on how we should live,” said Focus on the Family’s Daly.

“If they’re saying there will be no more violence if conservatives shut up and simply stop criticizing the world, I don’t think that’s an equation that works,” Daly said. “They rarely have the shoe on the other foot …

What do we do as a culture?”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!