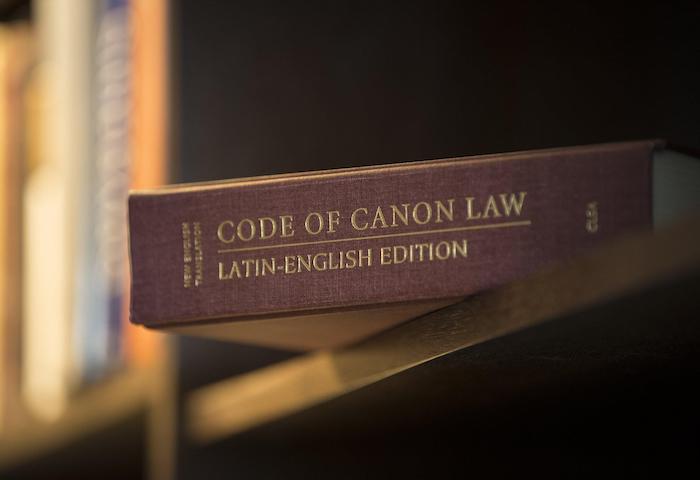

The Church needs a thorough revision of canon law and a commission to oversee this revision should include lay people, one of the country’s top barristers, Baroness Kennedy of The Shaws has said.

Speaking as part of a panel on the theme, Insisting on Sharing Authority at this week’s Root and Branch lay-led synod, the Scottish lawyer, broadcaster and Labour member of the House of Lords said a radical revision of canon law should be a “key call” from the synod.

She said a commission to oversee reform should “systematically go through the structures of the canon law and make them appropriate to the 21st century” and it should sit in public as it heard evidence.

Describing herself as “a firm believer in reform”, she said: “I really feel that we have to persuade the current leadership [in the Church] that they must cede power in order to survive.”

Elsewhere in the discussion, Baroness Kennedy called for an end to mandatory clerical celibacy. “I feel very strongly that you have to have abandon the business of celibacy.” She told the online discussion that clerical celibacy had been “one of the root problems in so many of the issues that we are talking about” and needed to be dealt with “first and foremost”.

“People are sexual beings. Some might choose to be celibate, and so be it. But there should be a possibility to follow a vocation even if you are a married person, male or female.”

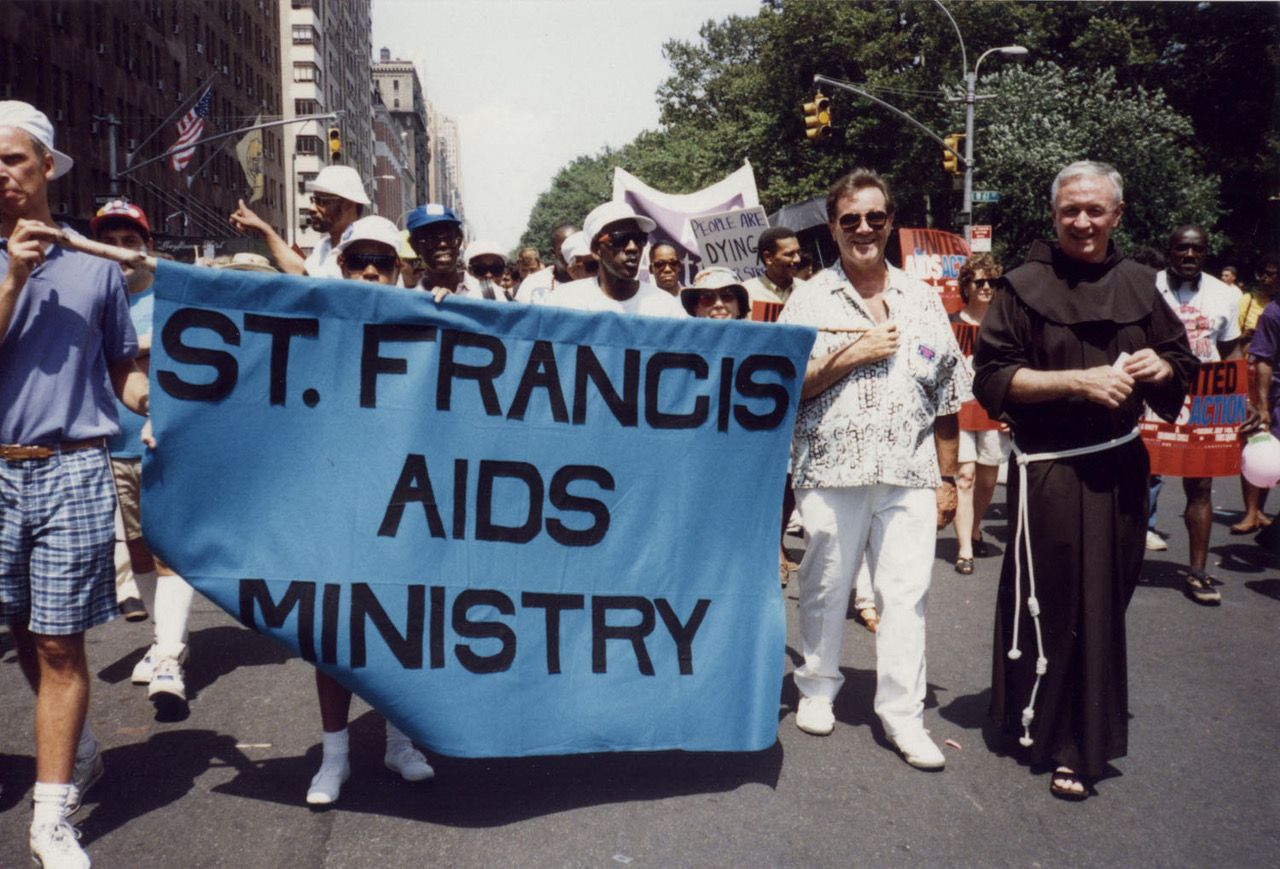

She also called on the Church to deal with its “hostility to homosexuality”.

She said: “We have to stop being so preoccupied and fetishistic about sex within the Church and start concerning ourselves with the suffering of the world.

“Our knowledge of humanity has developed, and science has helped us to understand sexuality so much better.”

Recalling the passing of the same sex marriage referendum in Ireland in 2015, Baroness Kennedy said that despite the Church having had such a dominant role in terms of power and authority, the people of Ireland by a majority voted for gay marriage. “It was because Catholic grandmothers and Catholic mothers and fathers said why should our child not have the same right to be with the person they love as our other child.”

She believed that there are “so many good things about the teachings of the church” which had given her a value system.

“The hierarchy has to be persuaded that this [reform] is about sustainability. The Catholic Church is not going to survive if it does not address these issues because the young are just not going to engage.”

Referring to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the need for a global template of values against which every legal system should be measured, including canon law, she asked: “Why has the Catholic Church not embraced it properly, particularly with regard to due process, the idea of access to justice – where was the access to justice for the many victims of sexual abuse within the Church?”

She said Church failures on abuse and moving people on who had committed crimes was one of the reasons so many people are now alienated from the Church.

“They do not see the Catholic Church adhering to that whole framework of human rights, rule of law, and respect for due process, access to justice, and the treatment of people as being equal before the law.”

She also hit out at the Church’s willingness to accommodate Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s desire to marry in a Catholic Church, which she had raised with Cardinal Nichols.

“People were very distressed, and I would say disappointed when they saw the ease with which the prime minister, who is not known for his sobriety when it comes to relationships with women, was able to have a marriage in the Catholic Church, despite the fact of being twice divorced.”

Recalling a conversation with a cab driver in Glasgow whose marriage had failed and who had remarried a catholic, he had told her of his pain at being unable to receive communion and feeling excommunicated.

“These are the things that are such a scar on the Church, and on all the people who still think of themselves as being Catholics, and who want to be able to take up the sacraments, to be a participant, to belong to this family. And yet, they are not able to do so.”

She had told the Cardinal: “Your communications strategy on saying everybody is equal before canon law is not working. You need to do something about that.”

The discussion on Wednesday was chaired by Virginia Saldanha, executive secretary of the Federation of Asian Bishops’ Conferences Women’s Desk.

It heard contributions also from Dr Luca Badini Confalonieri, Executive Director at the Wijngaards Institute, and broadcaster, writer and public speaker, Christina Rees, a member of the general synod of the Church of England.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!