By Cindy Wooden

The president of the Pontifical Academy for Life affirms his opposition to euthanasia and assisted dying but believes that to end confusion in the country, the Italian Parliament needs to make clear laws about withdrawing end-of-life care, his office said.

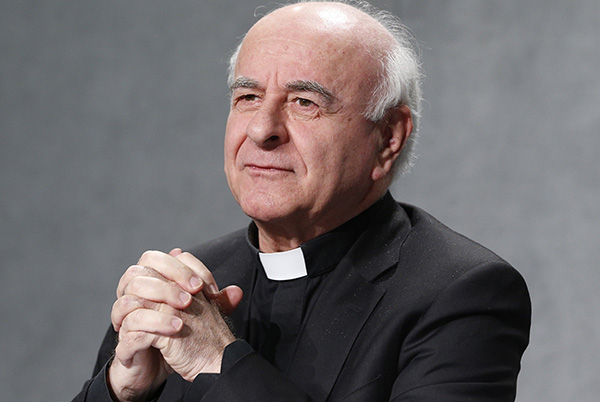

“Archbishop Vincenzo Paglia, president of the Pontifical Academy for Life, in full conformity with the church’s magisterium, reaffirms his ‘no’ to euthanasia and assisted dying,” his office said in a statement April 24.

The archbishop participated in a debate April 19 about end-of-life issues, and the complete text of his remarks was published April 21 by the Italian news site Il Riformista. Some websites, reporting on his remarks, claimed he defended euthanasia and medically assisted dying.

The experience of countries where medically “assisted death” is permitted by law, he had said, shows that “the pool of people admitted tends to expand; competent adult patients are joined by patients in whom decision-making capacity is impaired, sometimes severely,” for example, psychiatric patients, children, the elderly with cognitive impairment.

“Cases of involuntary euthanasia and deep palliative sedation without consent have thus grown,” the archbishop had said. “The overall result is that we are witnessing a contradictory outcome: in the name of self-determination, we are constricting the actual exercise of freedom, especially for those who are most vulnerable.”

The desire of terminally ill patients to spare themselves and their families further suffering — and sometimes, further expense — and the difficulty caregivers have in seeing their loved ones suffer have made questions about end-of-life care a pressing issue, he said.

Pain relief, palliative care and supportive accompaniment of the sick and their family members is essential, the archbishop had told his audience. With serious palliative therapy and accompaniment, he said, “in many cases the demand for euthanasia disappears, but not always.”

Euthanasia and physician-assisted dying are not legal in Italy. However, in 2019, the Constitutional Court ruled that those involved in an assisted dying are not punishable when the patient is “suffering from an irreversible pathology” causing “physical and psychological suffering that he or she considers intolerable” and is being kept alive by life-support treatments.

The court, which ruled only on the punishability of assisting or convincing someone to commit suicide, urged parliament to take up the matter with democratic debate and clear legislation to fill the legal void so the judiciary would not be left to regulate.

But Parliament has not succeeded in coming up with legislation, so requests for assistance in dying and suspected cases of assisting a suicide still are being handled by the courts. Right-to-die activists succeeded in gathering more than 1 million signatures for a referendum supporting the repeal of an article criminalizing active euthanasia, but the Constitutional Court blocked it in 2022, saying it would violate constitutional protections of human life.

In such a context, Archbishop Paglia had said, “it is not to be ruled out that a legal mediation is feasible in our society that would allow assisted dying under the conditions specified by Constitutional Court sentence 242/2019: the person must be being ‘kept alive by life-support treatment and suffering from an irreversible pathology, the source of physical or psychological suffering that he or she considers intolerable, but fully capable of making free and conscious decisions.’”

“Personally,” the archbishop told his audience, “I would not assist with a suicide, but I understand that legal mediation may be the greatest common good concretely possible under the conditions in which we find ourselves.”

The academy’s statement April 24 noted that the Italian Constitutional Court ruling referenced by the archbishop held that “assisting a suicide is a crime. It then enumerated four specific and particular conditions in which the crime carries no penalty.”

“In this precise and specific context, Archbishop Paglia explained that in his view a ‘legislative initiative’ — certainly not a moral one — could be possible which would be consistent with the decision, and which preserves both the criminality of the act and the conditions in which the crime carries no penalty, as the court requested Parliament to legislate.”

“For Archbishop Paglia, it is important that the decision holds that the criminality of the act remains and is not overruled,” his office said. “On the scientific and cultural level, Archbishop Paglia has always supported the need for accompaniment of the sick in the final phase of life, using palliative care and loving personal attention, to ensure that no one is left to face alone the illness and suffering, and difficult decisions, that the end of life brings.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!