— He was arrested protesting war and clashed with fellow bishops in supporting gay marriage and the ordination of women and championing victims of sex abuse by priests.

By Trip Gabriel

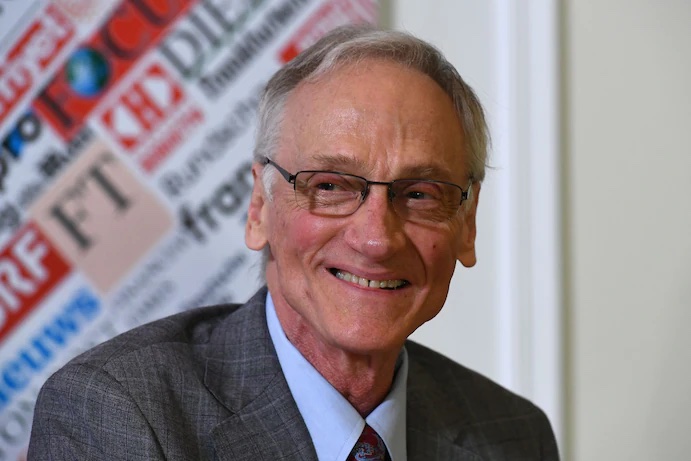

Thomas J. Gumbleton, a Roman Catholic bishop from Detroit whose nationally prominent support of liberal causes often clashed with church leadership, but who grounded his views in the 1960s Vatican reforms that promoted social justice, died on Thursday in Dearborn, Mich. He was 94.

His death was announced by the Archdiocese of Detroit, where he served for 50 years.

Bishop Gumbleton protested the United States’ involvement in the Vietnam War and U.S. foreign policy regarding Central America in the 1980s. He opposed fellow Catholic bishops by speaking out in favor of same-sex marriage and the ordination of women. He championed victims of clergy sexual abuse and blamed that advocacy for his ouster as pastor of St. Leo Catholic Church in Detroit in 2007, a contention that the archdiocese disputed.

As an activist for the sick and the poor, Bishop Gumbleton visited more than 30 countries, including Haiti, where he celebrated his 80th birthday in a pup tent after delivering medical supplies following a devastating earthquake in 2010. In El Salvador, he bore witness to the condition of villagers during the civil war there in the 1980s. He later protested outside the School of the Americas in Georgia, an Army facility that trained Salvadoran military leaders tied to death squads.

In the preface to a biography about him, “No Guilty Bystander: The Extraordinary Life of Bishop Thomas Gumbleton” (2023), by Frank Fromherz and Suzanne Sattler, Bishop Gumbleton wrote of a formative experience visiting Egypt as a young priest.

While looking for a place where Catholic tradition held that Mary and Joseph took Jesus after fleeing to Egypt, he entered a neighborhood in Cairo teeming with people living in the street, dressed in rags and hungry and thirsty. “I grew up in Michigan during the Depression,” he wrote. “It was a struggle for my parents to pay their bills and keep us dressed and fed. But our poverty was nothing like that which I experienced that day.”

“This was the first opening I had to the idea of trying to do justice in the world,” he added.

Bishop Gumbleton in 1972 became the first president of Pax Christi USA, a Catholic peace movement that promotes nonviolence and rejects preparation for war. In the preceding years, he urged the National Conference of Catholic Bishops to pass a resolution condemning the Vietnam War, but the majority opposed him.

“Obviously, for one who would follow the earliest Christian tradition, supporting the Vietnam War is morally unthinkable,” he wrote in an opinion essay in The New York Times in 1971.

He was later arrested at antiwar demonstrations, in 1999 protesting NATO bombing in Yugoslavia and in 2003 opposing the Iraq War.

In 1979, Bishop Gumbleton was one of three U.S. clergymen who traveled to Tehran for a Christmas Eve meeting with captive Americans in the U.S. Embassy during the Iranian hostage crisis. They held religious services and sang carols.

Despite his globe-trotting, Bishop Gumbleton considered himself an introvert and lived a spartan existence. He would often stay at a local Y.M.C.A. when traveling to church meetings. At St. Leo’s church, he had a bed on the floor in a room next to his office. In his car, he kept cash in the visor to give to homeless people.

Thomas John Gumbleton was born on Jan. 26, 1930, in Detroit, the sixth of nine children of Vincent and Helen (Steintrager) Gumbleton. His father worked for a manufacturer of car and truck axles. Thomas and three brothers attended Sacred Heart Seminary, a secondary school, though only Thomas continued on to become a priest. A sister, Irene Gumbleton, who survives him, became a nun, according to the National Catholic Reporter.

Thomas was ordained in 1956 after completing college-level work at St. John’s Provincial Seminary in Plymouth, Mich. In 1961, the Detroit diocese sent him to study in Rome, where he earned a doctorate in canon law. In 1968, at age 38, he was named an auxiliary bishop, the youngest bishop in the country at the time.

Detroit Catholic, a digital church publication, wrote of Bishop Gumbleton last week that his “early life and ministry were significantly influenced by the Second Vatican Council, which called upon the laity to take up a greater role in the Church, and for the Church to take a greater role in speaking out against injustice.”

His pacifism and other views were part of a progressive tradition in the Catholic Church. He was one of five bishops who, in 1983, drafted a landmark statement by the National Conference of Catholic Bishops that excoriated nuclear weapons.

But in later years his views diverged more acutely from the church mainstream, and he stopped attending the annual bishops’ conferences. He was never promoted above auxiliary bishop.

His views on gay and lesbian people, which he acknowledged had been stamped with the homophobia of his time, evolved faster than church doctrine, beginning when his youngest brother, Dan, came out as gay in the 1980s in a letter to family members. At first, Bishop Gumbleton feared that having a gay brother might affect his standing in the church, he told PBS in 1997, and he threw the letter aside without reading it to the end.

But when his mother asked him if her gay son would go to hell, Bishop Gumbleton said no, and he began a journey of acceptance that led him to speak to NPR about “the beauty of gay love” and to urge the church to accept same-sex marriage.

In the early 2000s, as scandals over sexual abuse of children by clergy convulsed American Catholicism, Bishop Gumbleton spoke out for victims and criticized church leaders for not openly confronting the problem. In 2006, he endorsed a bill in the Ohio State Legislature that would extend the statute of limitations for sex-abuse victims to file lawsuits.

Ohio’s bishops opposed the legislation, in line with Catholic leaders across the country who had resisted similar measures; they feared financial ruin, knowing that California dioceses were inundated with more than 800 lawsuits in 2003 during a one-year extension of limits on old sex-abuse claims.

In his testimony, Bishop Gumbleton revealed that as a teenager in high school he had been “inappropriately touched” by a priest.

“I don’t want to exaggerate that I was terribly damaged,” he told The Washington Post in 2006. “It was not the kind of sexual abuse that many of the victims experience.” But he said it had made him understand why young victims did not come forward for years.

In January 2007, during his last Mass as the pastor of St. Leo’s, Bishop Gumbleton told parishioners that he had been forced to step down in retaliation for speaking out.

The Detroit archdiocese disputed that assertion, saying that he had been removed because all bishops were required to submit a resignation at age 75, and that his had been accepted the previous year, though he had asked to continue as pastor of St. Leo’s. Replacing Bishop Gumbleton, a diocese spokesman said at the time, was not related to his political activity.

“I did not choose to leave St. Leo’s,” Bishop Gumbleton told parishioners. “It’s something that was forced upon me.”

Several accounts of his career emphasized that his outspokenness had thwarted his chances of ever being given a diocese of his own.

In a statement, Bishop John Stowe of Lexington, Ky., the current president of Pax Christi, the peace group, said Bishop Gumbleton had “preferred to speak the truth and to be on the side of the marginalized than to toe any party line and climb the ecclesiastical ladder.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!