— and release records on Kamloops

‘What we do want, is an apology, a public apology, not just for us but for the world … holding the Catholic Church to account’

By Tyler Dawson

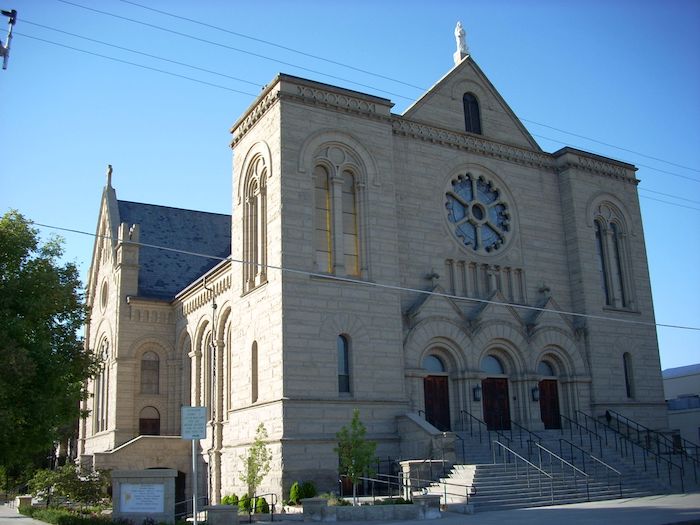

The chief of the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation has called upon the Catholic Church to issue a public apology for residential schools and for the order that ran the residential school in Kamloops, B.C., to release all of its records.

“What we do want, is an apology, a public apology, not just for us but for the world … holding the Catholic Church to account. There has never been an apology from the Roman Catholics,” said Rosanne Casimir, chief of the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation, on Friday, just over a week after the preliminary discovery of 215 unmarked graves at the former Kamloops Indian Residential School.

In the days since the announcement, “our nation has been consciously, collectively grappling with the heart-wrenching truth brought to light by the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc,” Casimir said in her first press conference, held over Zoom, since the discovery was announced.

Casimir said it was too soon to answer technical questions regarding the research itself or the costs and details of the preliminary findings, though reporters were told there would be weekly briefings. Instead, she thanked people for the outpouring of support and mentioned meetings the nation had held with B.C. Premier John Horgan and Carolyn Bennett, the federal Crown-Indigenous relations minister.

This is only the beginning

“This is only the beginning,” Casimir said. “We have a lot of work to do together. While the reality is shocking and we feel some level of anger, it is time to be gentle with ourselves and with each other.”

Casimir also took a moment to clarify a major piece of misinformation circulated by some media. “This is not a mass grave, but rather unmarked burial sites that are, to our knowledge, also undocumented. These are preliminary findings,” she said.

Last Thursday, the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation said the use of ground-penetrating radar had revealed “an unthinkable loss that was spoken about but never documented.”

“We had a knowing in our community that we were able to verify. To our knowledge, these missing children are undocumented deaths,” said Casimir said in a news release. “Some were as young as three years old.”

Official records kept by the Department of Indian Affairs, and recorded by the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation, show that 51 students died at the Kamloops school while it was in operation, from a wide array of causes: drowning, tuberculosis, food poisoning and sleeping sickness.

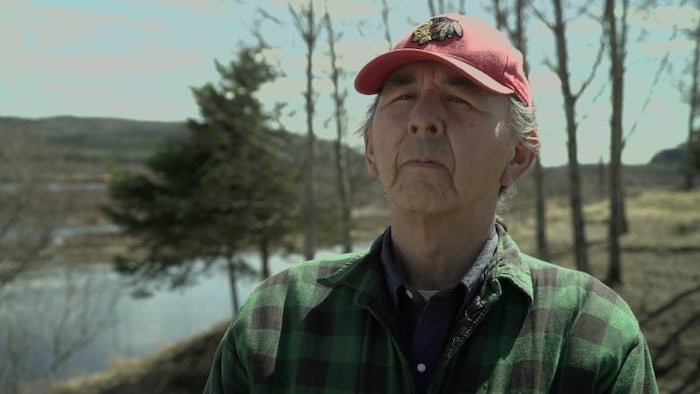

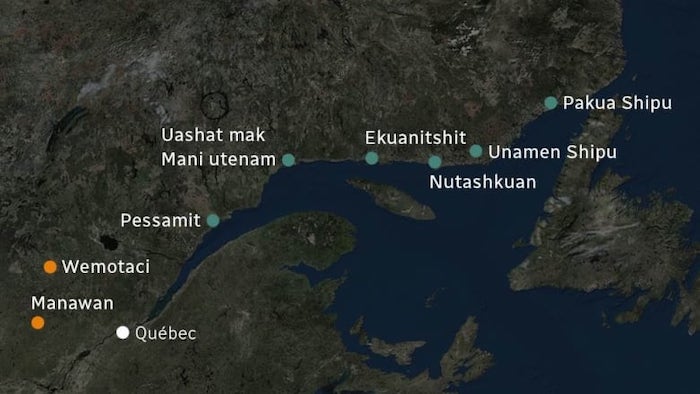

Overall the Truth and Reconciliation Commission estimated more than 6,000 deaths at residential schools across the country; the last closed in Saskatchewan in 1996. Murray Sinclair, a former senator and the chair of the commission, told CBC Radio that he believes the total could be as high as 25,000 dead, and called for an inquiry into all possible burial sites.“I suspect, quite frankly, that every school had a burial site,” Sinclair said.

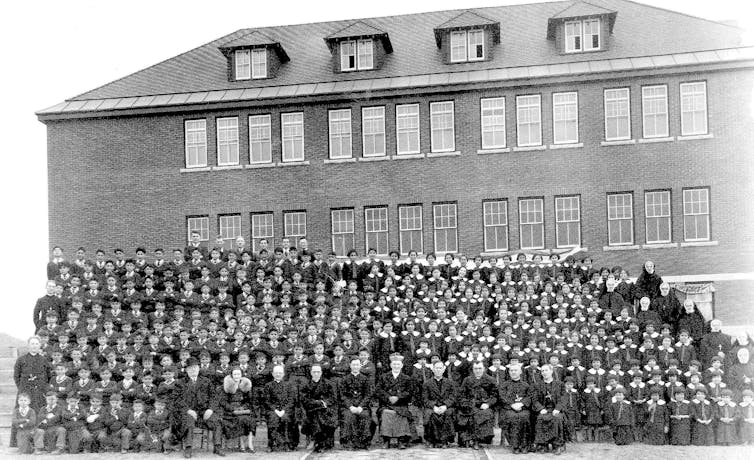

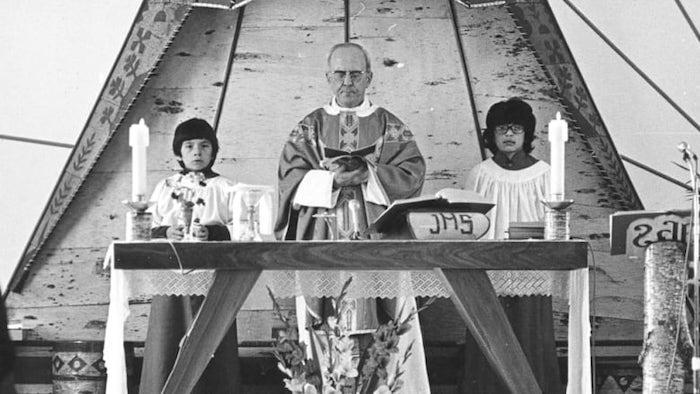

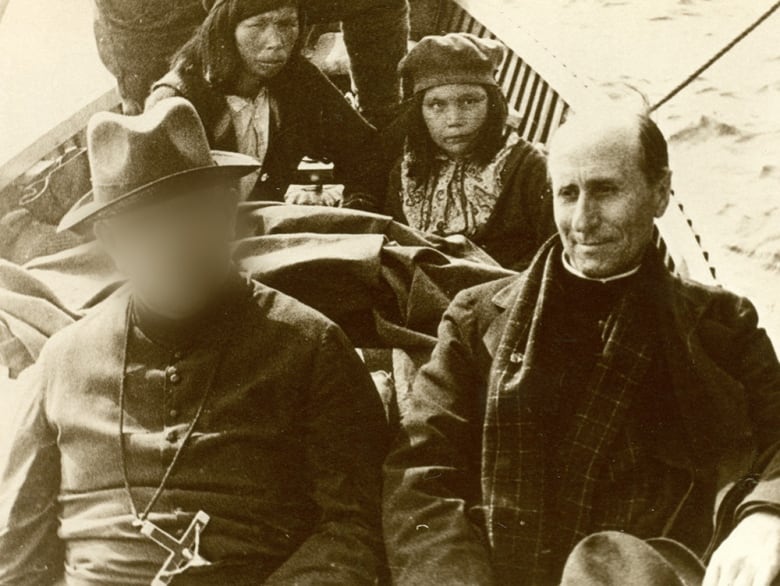

The Oblates of Mary Immaculate, a Catholic missionary order, ran the school in Kamloops; it operated as a residential school between 1890 and 1969 before being taken over by the federal government and ran as a residence for nearby day schools until its closure in 1978.

Casimir called on the order to release all of its records regarding the Kamloops school. Father Ken Thorson, with the OMI, said the order has already sent its archives to the Royal British Columbia Museum, but it is looking through other records to see if there is further valuable information.

Casimir noted that there was a “large discrepancy” between the number of dead previously identified through their records and what ground-penetrating radar has found.

“I don’t know if our records will shed further light on this discrepancy, but I’d hope it will, in service to the Tk’emlúps te Secwe̓pemc, in their search for clarity and understanding regarding the discovery in Kamloops last week,” Thorson said in a statement.

In the days since, there has been an outpouring of grief across the country and otherwise stalled or neglected acts of reconciliation, suddenly, became front of agenda.A school board in Calgary immediately moved to change the name of a school affiliated with one of the architects of the residential school program; the Senate created a national holiday in September; and many wore orange to commemorate those who died at the residential school.

Meanwhile, in Kamloops, the work continued.

The researcher, who has not spoken publicly, has continued the work of analyzing the ground-penetrating radar data; the nation says this preliminary work will be done by the end of June.

Ground-penetrating radar is technology used in archaeology, often to explore historic graveyards, that shows differences in soil beneath the surface; it doesn’t map underground, but rather shows changes that can be analyzed further to draw conclusions about what’s been found.

The Royal Canadian Mounted Police and B.C. Coroners Office have been contacted and are involved, though in what capacity remains unclear, both having deferred to the leadership of the First Nation, which noted the historically fraught relationship between police and Indigenous people in Friday’s press conference.

Asked whether the former Kamloops Indian Residential School should be torn down, Casimir said the First Nation believes it should remain standing.

“It is a very huge piece of history that we do not want to be forgotten.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!