Sexual abuse of Innu, Atikamekw children at hands of missionaries was rampant, Enquête finds

By

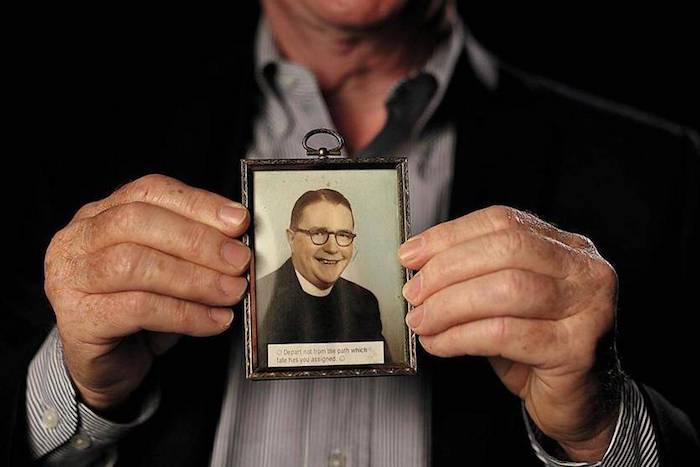

“He’d let us drive. He knew how to do everything. We were impressed to see a priest act that way,” recalls Jason Petiquay.

Petiquay was 11 when he was sexually abused by Raynald Couture, an Oblate missionary who worked in Wemotaci, Que., from 1981 to 1991.

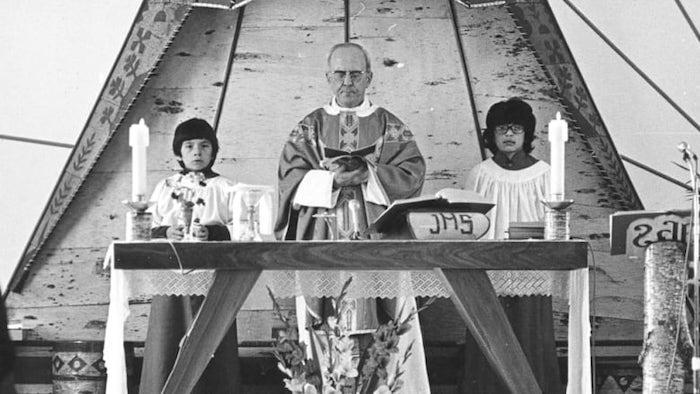

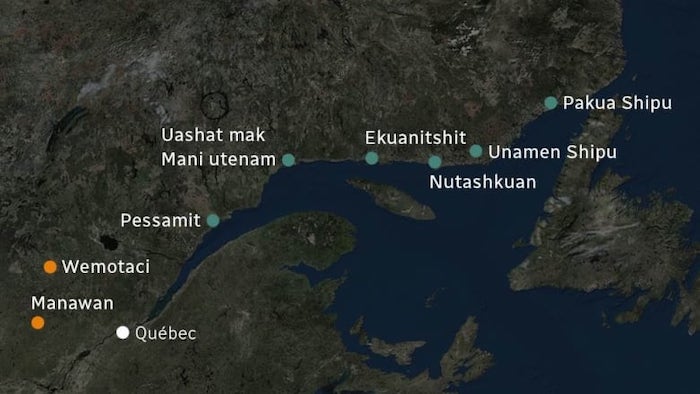

The Atikamekw community 285 kilometres north of Trois-Rivières was one of many remote First Nations communities in Quebec where priests belonging to the Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate (OMI) were spiritual leaders and authority figures for generations.

Petiquay described how Couture would lure young boys to his cabin by inviting them for a ride on his all-terrain vehicle or in his pick-up truck.

His story of abuse is one of dozens Atikamekw and Innu people in Quebec told Radio-Canada’s investigative program Enquête in a report set to air Thursday evening.

It paints of bleak portrait of widespread sexual abuse at the hands of at least 10 Oblate priests in eight different communities served by the missionary order, which began its evangelization work among Inuit and First Nations in Canada in 1841.

MMIWG shines light on decades-old secret

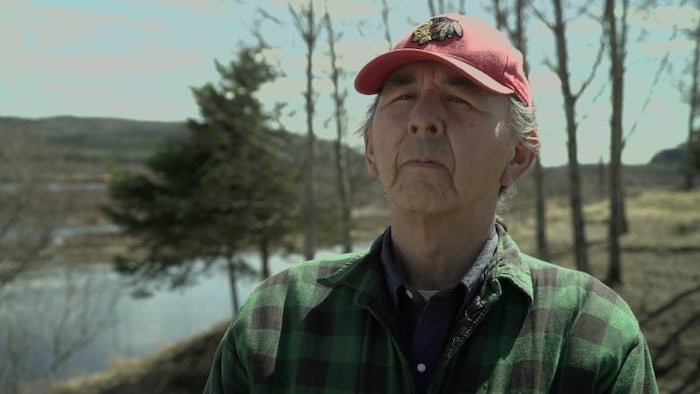

It has been almost a year since women from the isolated Innu communities of Unamen Shipu and Pakua Shipu, on Quebec’s Lower North Shore, described how they were sexually assaulted by an Oblate priest who worked in their territory for four decades, until his death in 1992.

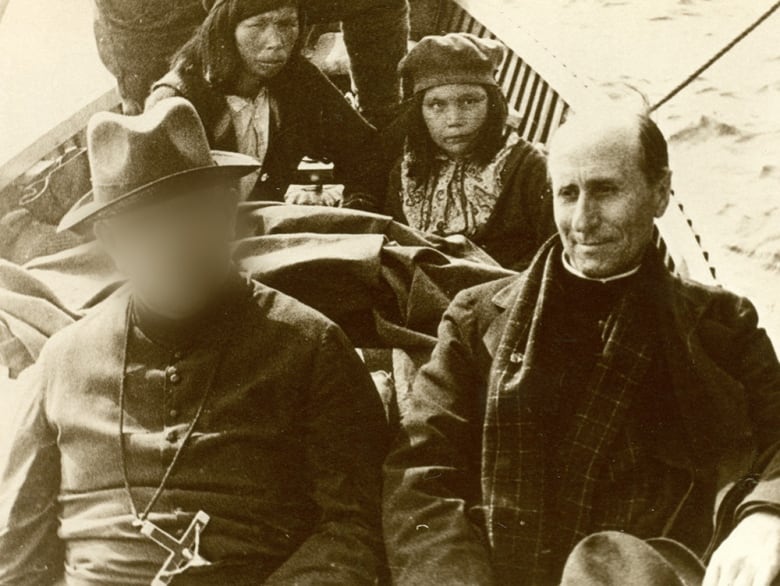

One after another, alleged victims of the Belgian native, Father Alexis Joveneau, told the federal inquiry into missing and murdered Indigenous women (MMIWG) how the charismatic and much-admired priest had abused them as children.

“I could not talk about it,” Thérèse Lalo told commissioners. “He was like a god.”

In the wake of the testimony from Lalo and others, the Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate issued an apology, setting up a hotline and offering psychological support to Joveneau’s alleged victims.

“We are absolutely devastated by these troubling testimonies,” the OMI’s Quebec office said in a March statement.

But the allegations in the Enquête report suggest the religious order’s superiors long knew about allegations against Joveneau.

Francis Mark, an Innu man from Unamen Shipu who said he was assaulted by Joveneau, said many years ago, he turned for help to the late Archbishop Peter Sutton, an Oblate who was made bishop of the Labrador City-Schefferville diocese in 1974.

“He let me down,” said Mark. “He didn’t guide me. Was there justice? No.”

Devout elders kept silence

In some instances which Enquête looked into, when Oblate superiors or church officials were told about the abuse, the priests were simply sent to neighbouring communities, where other Indigenous children were abused in turn.

In other cases, as in that of Father Raynald Couture in Wemotaci, deeply religious elders in the community insisted on silence.

“The mushums, the kookums [grandmothers and grandfathers], they asked him to stay in the community,” said Charles Coocoo, a Wemotaci man who once demanded that Couture leave.

Mary Coon, a social worker at the time, went straight to the religious order to ask them to intervene, but without an official police complaint, the Oblates refused.

“The boys wouldn’t file a complaint,” said Coon. “We wanted to get him out of here, but how could we? There was no complaint. We had nothing.”

In 1991, Couture was sent to France, where he remained until eight of his victims pressed charges. In 2004, he was sentenced to 15 months in jail, a punishment another victim, Alex Coocoo, called so light as to be “ridiculous.”

‘A sin to talk’

Claude Niquay said he was a seven-year-old altar boy when he alleges he was first molested by Father Clément Couture, another Oblate missionary who was posted in Manawan, an Atikamekw community southwest of Wemotaci, until 1996.

Niquay was forced to see his alleged abuser every day, when he delivered meals cooked by his grandmother to the priest.

When he tried to tell his grandmother about the assaults, he was punished.

“She’d tell me to go sit in a corner, that it was a sin to talk about those things,” he said.

Before Couture’s arrival, the community had been served by two other Oblate priests, Édouard Meilleur, and later, Jean-Marc Houle, whose alleged victims — elderly now — still recall their assaults vividly.

Antoine Quitish was just five when Meilleur allegedly stripped off his cloak and forced himself on him, “poking” Quitish’s chest with his penis.

“I’m happy that [the story] is out now,” said Quitish, now 75.

Other Atikamekw elders described Meilleur as an exhibitionist who would slip his hands under girls’ dresses during confession.

Enquête heard how Houle, who was posted in Manawan from 1953 to 1970, was drawn to pregnant women: he’s alleged to have spread holy oil over the stomachs, the breasts and the genitals of his victims, explaining he was warding off the devil in their unborn children.

The stories got out.

“I told the archdiocese, ‘If you don’t get that guy out of there, tomorrow morning it will be on the front page of the newspapers’,” recalls Huron-Wendat leader Max Gros-Louis, then the head of the Association of Indians of Quebec.

Houle was removed, said Gros-Louis — only to be sent to the Innu community of Pessamit, on Quebec’s North Shore.

Community warned of priest’s behaviours

Robert Dominique, then a band councillor in Pessamit, said his Atikamekw friends warned him about Houle, but the culture of the time ensured his silence.

“For elders, their faith is deeply rooted,” Dominique said. “Religion is sacred.”

Saying out loud that a priest was violating women and children was inconceivable, Gros-Louis agreed.

“You wouldn’t be allowed to go out anymore. You’d be banished, excommunicated,” he said.

There is no evidence Houle’s alleged assaults continued in Pessamit. However, people in that community recall abuse by three Oblate priests who preceded him.

Dominique’s sister, Rachelle, alleges she was first assaulted by Father Sylvio Lesage in the 1960s, and when Father Roméo Archambault replaced him in the 1970s, for her, things got worse.

He would take her into the church basement, she remembers.

“He was behind me, holding my little breasts,” she alleges, “and after I had to masturbate him in the dark.”

She described feeling “broken, vilified.”

Jean-Yves Rousselot also recounted being sexually assaulted by Archambault — alleged assaults that continued when that Oblate missionary was replaced by Father René Lapointe. The young altar boy told his grandfather what had happened and was beaten.

“I had to go to confession, to confess that I had committed blasphemy,” Rousselot said.

Lapointe was his confessor.

The priest would later be relocated to another Innu community, Nutashkuan, where he remained for 30 years, allegedly paying children to masturbate him.

In 2003, provincial police launched an investigation following a complaint, but charges were never laid.

Class action suit awaits Oblates

In the Innu community of Mani-Utenam, Gérard Michel recalls community elders sending him, along with another young man, to Baie-Comeau in 1970 to ask the archbishop to remove Father Omer Provencher, who is alleged to have been sexually assaulting girls in the community.

Nothing was done.

“Nothing, nothing, nothing,” said Michel, now an elder himself.

Provencher, who left the priesthood to live with an Innu woman years ago, told Enquête he will not answer any questions until he is formally charged with a crime.

Father René Lapointe, the priest who spent three decades in Nutashkuan, denies he ever sexually assaulted children.

Now at the Oblates’ retirement home in Richelieu, he told Enquête there is absolutely no truth in any of it.

“Nothing is true in that story. These are all inventions,” he said.

Raynald Couture, the Oblate priest who was found guilty of sexually assaulting children in Wemotaci, lives in the same retirement home.

He admits his past crimes.

“I drank like a bastard, and that’s when those things happened,” he told Enquête. He called his assaults “a weakness” and then a “game with the children,” and said he sought help from his superiors, asking to see the Oblates’ psychologist.

“They never even came,” he said.

Most of the priests accused of having assaulted so many Innu and Atikamekw people as children are dead now; Father Alexis Joveneau, who died in 1992, is buried in the cemetery in Unamen Shipu, where he spent so many years.

In late March, just days after the Oblates issued their apology and set up a hotline for Joveneau’s alleged victims, a class action suit was launched in Quebec for all victims of sexual assault at the hands of Oblate priests.

Lawyer Alain Arsenault says to date, 48 victims have come forward, alleging they were assaulted by 14 different Oblate missionaries.

With the court case pending, the head of the Oblates’ Quebec office, Father Superior Luc Tardif, turned down a request to be interviewed for this story.

Regardless of the results of that lawsuit, people in Unamen Shipu are asking that Joveneau’s remains, buried next to their Innu loved ones, be exhumed and taken away.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!