Cardinal O’Malley is credited with going public when many dioceses have not, but critics say he has stopped far short of a full accounting

Robert M. Burns pleaded guilty to raping and sexually assaulting five boys while working as a priest in Jamaica Plain and Charlestown, earning an eight- to 11-year sentence that he is still serving at the Old Colony Correctional Center.

Even before Burns went to the Bridgewater prison, the Boston Archdiocese paid several of his victims – including two who later died of drug overdoses – more than $2 million to settle claims of abuse after their lawyers discovered that church officials had assigned Burns to parish work knowing he had a history of molesting children.

Cardinal Sean P. O’Malley has called it proper to omit the clerics — most of them priests, but also deacons and brothers — because they are ultimately supervised by other church officials.

Cardinal Sean P. O’Malley has called it proper to omit the clerics — most of them priests, but also deacons and brothers — because they are ultimately supervised by other church officials.

But last August, when Cardinal Sean P. O’Malley published a long-awaited official roster of 159 clerics publicly accused of abusing minors, Burns’ name was not on it. The reason: Burns, who served as a parish priest in Boston for nearly a decade, was originally a priest of the Youngstown Diocese in Ohio.

O’Malley, facing opposition from some in the church to publishing such a list at all, in the end released a very selective accounting, limited to priests originally from the Boston Archdiocese – and thus directly under its supervision – and excluding members of religious orders, including O’Malley’s own Capuchin friars.

The result is that 70 accused clerics, including some with notorious reputations and many alleged victims, are not listed at all, a Globe review of church records has found. To critics of the church it is a disheartening sign that nearly 10 years after Boston became the epicenter of the global sexual abuse crisis in the Catholic Church, the Boston Archdiocese is still struggling to face its troubled past.

The cardinal’s decision has also undercut his reputation as a reformer among some victims of clergy abuse, who worry that omitting any accused abuser’s name from the official list, which is published on the archdiocese’s website, only lowers the chances of further victims summoning the courage to come forward. It puts him at odds with most of the 33 dioceses that have released more complete lists of accused priests, though it compares favorably with the vast majority of the nation’s 195 dioceses, which have released no official lists at all.

Among those left off the Boston list are Fidelis DeBerardinis, a Catholic brother completing an eight-year prison term for preying on altar boys at an East Boston parish; the late Rev. Paul M. Desilets, a one-time Bellingham priest who served 17 months for molesting more than a dozen altar boys; and the Rev. James F. Talbot, who served a six-year sentence for raping two Boston College High School students.

O’Malley, who declined requests for an interview, has called it proper to omit the clerics – most of them priests, but also deacons and brothers – because they are ultimately supervised by other church officials. In a seven-page letter that accompanied his list of accused clerics he said he decided to leave them out “because the Boston Archdiocese does not determine the outcome in such cases; that is the responsibility of the priest’s order or diocese.’’

But survivors of clergy abuse and their advocates consider it a flawed rationale, since so many of the nearly 600 priests working in the Boston Archdiocese – more than 40 percent – are affiliated with religious orders, such as the Jesuits or O’Malley’s own Capuchin Franciscans, or came from other jurisdictions.

All accused abusers, no matter their provenance, should be considered the archdiocese’s responsibility and concern, they say.

“It’s heartbreaking to think the church has all this information about accused religious order priests and priests from other dioceses and isn’t releasing it,’’ said Terence McKiernan, the founder of BishopAccountability.org, a group that maintains records of accused clergy and also advocates for victims. “O’Malley’s list is just one pretty obvious example of a concerted effort to appear transparent and pastoral while trying to make sure that a lot of this goes back under the radar.’’

Church law cited

In leaving out the names of religious order and visiting priests, O’Malley cited canon law, or church law, saying it is up to the superior of a religious order or the bishop of a home diocese to investigate clergy abuse accusations.

But church records show that the Boston Archdiocese has often investigated accusations against religious order and visiting priests – and paid their alleged victims to settle damage claims.

Indeed, the Vatican has allowed bishops wide discretion in responding to the clergy sexual abuse crisis, and bishops in some other dioceses have not felt bound by a narrow reading like O’Malley’s, according to a recent survey by BishopAccountability.org.

Among those who have released lists that include the names of religious order and visiting clerics are major Catholic jurisdictions, such as the archdioceses of Baltimore and Los Angeles, the largest in the United States.

Some of those church leaders said they felt compelled to issue as complete a list as possible, to maximize its potential usefulness for those who say they were abused.

“We felt it was important to name them to fulfill the purpose for putting the list out, which was to ensure that if there were other victims they would feel encouraged to come forward,’’ explained Bishop Gerald F. Kicanas of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Tucson, whose list of accused priests includes both religious order and visiting clerics.

The Tucson diocese also disclosed the names of priests – both alive and dead – who have faced accusations that have never been made public. O’Malley’s list omitted the names of 91 accused clerics of the Boston Archdiocese, most of whom are dead and are not the subject of public accusations. That means that of a total of 320 priests here who have faced some form of accusation, 161 – the 91 plus the 70 from religious orders and other jurisdictions – are not on the archdiocesan website’s tally of names.

Some critics say that O’Malley’s approach is designed to limit the likelihood of new victims coming forward and thus of future financial liability for an archdiocese that has already paid out $147 million in settlements and another $43.5 million to cover legal costs, counseling for victims, and sexual abuse prevention initiatives.

“The driving force in not releasing a full list is money,’’ said Mitchell Garabedian, an attorney who represents clergy sex abuse victims.

New victims often step forward following publicity about abusive priests, even when they’ve been publicly accused before, which is what happened in the case of the late Czeslaw “Chester’’ Szymanski, a religious order priest who worked in Lowell’s Holy Trinity parish during the 1980s and whose alleged victims only recently began stepping forward.

Last December, attorney Carmen L. Durso held a news conference where he released statements by three men from a tightly-knit Polish community who said they were sexually molested by Szymanski, who was not included in O’Malley’s list.

At Sunday Mass two days later, the church pastor, the Rev. Stanislaw Kempa, denounced Szymanski’s accusers as “cowards.’’ Then, on the following Sunday, O’Malley sent one of his bishops to Holy Trinity to apologize for Kempa’s use of the pulpit “as a platform for harmful words.’’

With the news media covering each development, five additional alleged victims stepped forward.

Recently, all eight completed negotiations for damages and are slated to receive a total of $600,000, to be paid by the archdiocese and the Order of St. Paul, Szymanski’s religious order.

Keeping the list of accused clerics short may also ease the internal pressure O’Malley has faced from priests who opposed his decision to release such a list in the first place.

But Massachusetts’ chief law enforcement official warned O’Malley in advance that his list would draw public criticism. Attorney General Martha Coakley, a former Middlesex District Attorney who supervised the prosecution of the late Rev. John J. Geoghan, a serial pedophile and a symbol of the Boston abuse crisis, said she repeatedly told the archdiocese that O’Malley’s plan was inadequate to ensure public safety and assuage the concerns of victims.

“By failing to name the visiting priests and those from religious orders they’re sending a mixed message to the public, some of whom may still be incredibly angry,’’ Coakley said in an interview.

Strong start fizzles

When he arrived in Boston in 2003, O’Malley faced a daunting task: healing the wounds of a historic diocese in the most Catholic major city in America that was still reeling from an unprecedented scandal. And O’Malley seemed to be an ideal candidate for the job.

To many committed Catholics, his brown robe and sandals – the attire of a Capuchin friar – symbolized a refreshingly humble alternative to his predecessor, the imperious Cardinal Bernard F. Law, who resigned as archbishop and decamped for Rome after 58 of his priests signed a letter urging him to quit because of his handling of the burgeoning abuse crisis.

Moreover, by the time O’Malley introduced himself to beleaguered parishioners, the nation’s Catholic bishops already had approved a “Charter for the Protection of Children and Young People,’’ in which they pledged to safeguard children and end the secrecy surrounding the issue.

Almost immediately, O’Malley undertook a series of initiatives aimed, he said, at ensuring that “the tragedy of sexual abuse is never repeated in the church.’’ Over the next decade, church officials provided “safe environment training’’ to 300,000 children and taught 175,000 adults – including archdiocesan and religious order priests and seminarians – to identify and report suspected sexual abuse.

In addition, the church conducted more than 60,000 annual criminal background checks on archdiocesan and religious order priests, deacons, educators, and others who work with children.

To O’Malley’s supporters, these initiatives reflected a career spent trying to prevent child sexual abuse, including earlier assignments in the dioceses of Fall River and Palm Beach, Fla., where he proved adept at stemming the outrage of parishioners after major scandals.

But along the way, others questioned O’Malley’s commitment to fully disclosing the church’s role in the sex abuse crisis. In 2002, then-Bristol District Attorney Paul F. Walsh Jr. criticized O’Malley at a press conference at which Walsh released the names of 20 priests who he said had been accused of abusing minors.

He also said O’Malley had impeded his investigation by declining to turn over the names of accused clergy, a charge he stands by today.

“I have no warm feelings for that guy,’’ said Walsh, a onetime altar boy and graduate of Catholic-led Providence College. “I don’t think he ever lied to me but I’m convinced he never told me the full truth.’’

‘Electronic wall of shame’

From the moment Cardinal O’Malley announced plans to release a list of priests accused of sexual abuse, in 2009, many of his priests opposed the idea.

During a March 2009 meeting of O’Malley’s Presbyteral Council, an advisory group of clergy, the Rev. Peter G. Gori of St. Augustine’s Church in Andover gave O’Malley’s plan an unflattering name, referring to the proposed roster as an “electronic wall of shame.’’

“The ramification to priest morale hangs in the balance,’’ Gori continued, according to minutes of council meetings provided to the Globe through a priest who wished to remain anonymous because he was not authorized to release them.

“The priests who are speaking in favor of the concept have been less, by far, than those who are opposed,’’ reported a top O’Malley aide, the Rev. Richard Erikson, during another council meeting in 2010.

Apart from the opposition expressed at the meetings, some priests still argue that O’Malley should be compelled to do no more than what civil law requires, which is to publicize only the names of convicted sexual offenders deemed at high risk of offending again.

“Do the names of teachers who’ve been accused of committing sex crimes get posted on a list available to the public?’’ said the Rev. David M. O’Leary, the Catholic Chaplain at Tufts University and one of the 58 priests who signed the letter urging Law to resign. “Let’s treat everyone fairly.’’

O’Malley chose to read his obligation neither as narrowly as some priests urged, nor as spaciously as those representing alleged victims want. His decision to omit religious order and visiting clerics meant his listing did not apply to a category of clergy that accounts for more than 40 percent of the 1,310 priests working in the archdiocese today.

The archdiocese has acknowledged that O’Malley has at least some authority over these priests. In his letter, O’Malley said that whenever an order or visiting priest is credibly accused of abusing a minor, he rescinds the priest’s permission to minister here, reports the accusation to local law enforcement, and informs the priest’s order or home diocese.

“I hope that other dioceses and religious orders will review our policy and consider making similar information available to the public,’’ O’Malley said.

But so far, none of the religious orders, including O’Malley’s Capuchin friars, have released the names of accused clerics.

A clear signal wanted

If priests were unhappy that O’Malley named so many accused priests, sex abuse victims felt betrayed because the church named so few, in many cases leaving out their abusers. Victims interviewed by the Globe said O’Malley should have named the religious order and visiting priests in part to encourage more victims to step forward, and in part to send a clear signal that the church accepts responsibility for the behavior of all abusive priests.

“To sweep a good number of these guys under the rug and not mention their names I think is really a shame,’’ said Jim Higgins, a 56-year-old Florida resident who said he was molested in the early 1970s by Talbot, the Jesuit priest who served a six-year sentence for raping two Boston College High School students and who was left off O’Malley’s list.

Brian E. Corriveau, a 46-year-old Westborough resident who said he was molested by Desilets – the one-time Bellingham priest who was excluded from O’Malley’s list because he was from a religious order based in Canada – said O’Malley’s decision came as no surprise. “I’m very jaded about the Catholic Church at this point,’’ he said. “I expect them to keep covering up.’’

But few could feel worse than one of Szymanski’s alleged victims, who waited more than 20 years before speaking out.

The alleged victim, who asked for anonymity because several family members retain ties to the church, said he advised one younger student against serving as an altar boy in the 1980s, but didn’t go public until last December, after he heard that the Holy Trinity pastor had branded Szymanski’s accusers “cowards.’’

“What still haunts me is I didn’t save everybody else,’’ he said. “We’re 25 years down the road and the guilt over not doing anything back then just kills me.’’

Complete Article HERE!

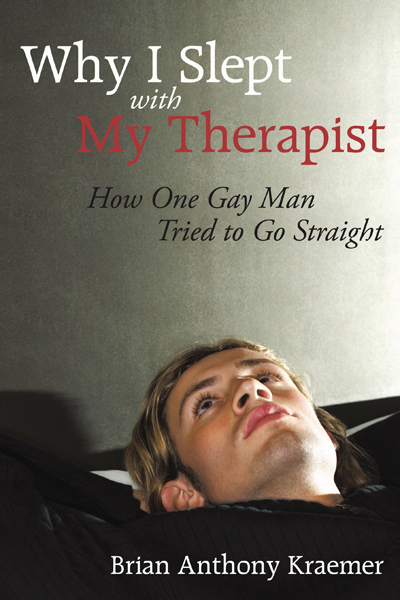

Just how far will a gay man go to be straight? For Brian Anthony Kraemer, that journey included thirteen years of celibacy, daily prayer, extensive reading, participation in an ex-gay ministry, and two exorcisms. He still hadn’t reached his goal when he met a man he believed to be the therapist of his dreams—a married, Christian therapist with an innovative method of healing.

Just how far will a gay man go to be straight? For Brian Anthony Kraemer, that journey included thirteen years of celibacy, daily prayer, extensive reading, participation in an ex-gay ministry, and two exorcisms. He still hadn’t reached his goal when he met a man he believed to be the therapist of his dreams—a married, Christian therapist with an innovative method of healing.