In the annals of the sexual abuse scandals in the Roman Catholic Church, most of the cases that have come to light happened years before to children and teenagers who have long since grown into adults.

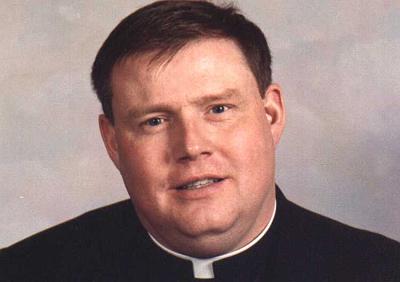

But a painfully fresh case is devastating Catholics in Kansas City, Mo., where a priest, who was arrested in May, has been indicted by a federal grand jury on charges of taking indecent photographs of young girls, most recently during an Easter egg hunt just four months ago.

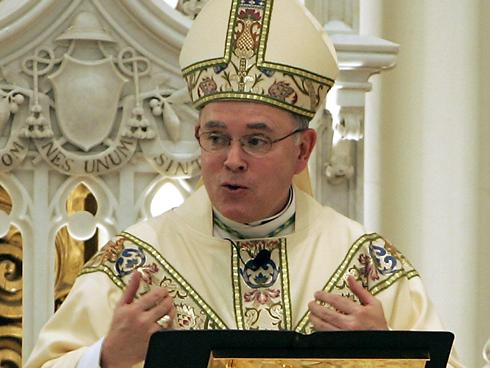

Bishop Robert Finn of the Diocese of Kansas City-St. Joseph has acknowledged that he knew of the existence of photographs last December but did not turn them over to the police until May.

A civil lawsuit filed last week claims that during those five months, the priest, the Rev. Shawn Ratigan, attended children’s birthday parties, spent weekends in the homes of parish families, hosted the Easter egg hunt and presided, with the bishop’s permission, at a girl’s First Communion.

“All these parishioners just feel so betrayed, because we knew nothing,” said Thu Meng, whose daughter attended the preschool in Father Ratigan’s last parish.

“And we were welcoming this guy into our homes, asking him to come bless this or that. They saw all these signs, and they didn’t do anything.”

The case has generated fury at a bishop who was already a polarizing figure in his diocese, and there are widespread calls for him to resign or even to be prosecuted.

Parishioners started a Facebook page called “Bishop Finn Must Go” and are circulating a petition.

An editorial in The Kansas City Star in June calling for the bishop to step down concluded that prosecutors must “actively pursue all relevant criminal charges” against everyone involved.

Stoking much of the anger is the fact that only three years ago, Bishop Finn settled lawsuits with 47 plaintiffs in sexual abuse cases for $10 million and agreed to a long list of preventive measures, among them to immediately report anyone suspected of being a pedophile to law enforcement authorities.

Michael Hunter, an abuse victim who was part of that settlement and is now the president of the Kansas City chapter of the Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests, said: “There were 90 nonmonetary agreements that the diocese signed on to, and they were things like reporting immediately to the police. And they didn’t do it. That’s really what sickens us as much as the abuse.”

The bishop has apologized and released a “five-point plan” that he described as “sweeping changes.”

He hired an ombudsman to field reports of suspicious behavior and appointed an investigator to conduct an independent review of the events and diocesan policies.

The investigator’s report is taking longer than expected and is now due in late August or early September, said Rebecca Summers, director of communications in the diocese.

The bishop also replaced the vicar general involved in the case, Msgr. Robert Murphy, after he was accused of propositioning a young man in 1984.

The diocese has delayed a capital fund-raising campaign on the advice of its priests, a move first reported by The National Catholic Reporter.

Bishop Finn, who was appointed in 2005, alienated many of his priests and parishioners, and won praise from others, when he remade the diocese to conform with his traditionalist theological views.

He is one of few bishops affiliated with the conservative movement Opus Dei.

He canceled a model program to train Catholic laypeople to be leaders and hired more staff members to recruit candidates for the priesthood.

He cut the budget of the Office of Peace and Justice, which focused on poverty and human rights, and created a new Respect Life office to expand the church’s opposition to abortion and stem cell research.

He set up a parish for a group of Catholics who prefer to celebrate the old Tridentine Mass in Latin.

Father Ratigan, 45, was also an outspoken conservative, according to a profile in The Kansas City Star. He and a class of Catholic school students joined Bishop Finn for the bus ride to the annual March for Life rally in Washington in 2007.

The diocese was first warned about Father Ratigan’s inappropriate interest in young girls as far back as 2006, according to accusations in the civil lawsuit filed Thursday.

But there were also more recent warnings.

In May 2010, the principal of a Catholic elementary school where Father Ratigan worked hand-delivered a letter to the vicar general reporting specific episodes that had raised alarms: the priest put a girl on his lap during a bus ride and allowed children to reach into his pants pockets for candy.

When a Brownie troop visited Father Ratigan’s house, a parent reported finding a pair of girl’s panties in a planter, the letter said.

Bishop Finn said at a news conference that he was given a “brief verbal summary” of the letter at the time, but did not read it until a year later.

In December, a computer technician discovered the photographs on Father Ratigan’s laptop and turned it in to the diocese.

The next day, the priest was discovered in his closed garage, his motorcycle running, along with a suicide note apologizing to the children, their families and the church.

Father Ratigan survived, was taken to a hospital and was then sent to live at a convent in the diocese, where, the lawsuit and the indictment say, he continued to have contact with children.

Parents in the school and parishioners were told only that Father Ratigan had fallen sick from carbon monoxide poisoning. They were stunned when he was arrested in May.

“My daughter made cards for him,” said one parent who did not want her name used because the police said her daughter might have been a victim. “We prayed for him every single night at dinner. It was just lying to us and a complete cover-up.”

A federal grand jury last Tuesday charged Father Ratigan with 13 counts of possessing, producing and attempting to produce child pornography.

It accused him of taking lewd pictures of the genitalia of five girls ages 2 to 12, sometimes while they slept.

If convicted, he would face a minimum of 15 years in prison.